Today, ESET Research releases a white paper updating our understanding of the Winnti Group. Last March, ESET researchers warned about a new supply-chain attack targeting video game developers in Asia. Following that publication, we continued those investigations in two directions. We were interested in finding any subsequent malware stages delivered by that attack, and we also tried to find how the targeted developers and publishers were compromised to deliver the Winnti Group’s malware in their applications.

While we continued that investigation of the Winnti Group, additional reports on their activities were published. Kaspersky released details about the ShadowHammer malware that was found in the Asus Live Update utility. That report also mentioned some of the techniques we describe in detail in this new white paper, such as the existence of a VMProtect packer and a brief description of the PortReuse backdoor. FireEye also published a paper about a group it calls APT41. Our research confirms some of their findings regarding the subsequent stages in some of the supply-chain attacks, such as the use of compromised hosts for mining cryptocurrencies.

Our white paper provides a technical analysis of the recent malware used by the Winnti Group. This analysis further refines our understanding of their techniques and allows us to infer relationships between the different supply-chain incidents.

We hope the white paper and indicators of compromise we release today will help targeted organizations find if they are victims or prevent future compromise.

A note about naming

There are lots of reports about this group’s — or perhaps these groups’ — activities. It seems each report gives new names to the group and the malware. Sometimes, this has been because the link with existing research wasn’t strong enough to classify the malware and activities of interest under a previous name, or, because vendors or research groups have their own classifications and naming and used them in their public reporting. For someone who doesn’t actually analyze the malware samples, it can be difficult to confirm aliases and easy to add more confusion.

We have chosen to keep the name “Winnti Group” since it’s the name first used to identify it, in 2013, by Kaspersky. We do understand Winnti is also a malware family: that is why we always write Winnti Group when we refer to the malefactors behind the attacks. Since 2013, it was demonstrated that Winnti is only one of the many malware families used by the Winnti Group.

To be clear, we do not exclude the idea that there might be multiple groups using the Winnti malware. For the scope of our research we refer to them as potential subgroups of the Winnti Group because there is no evidence they are completely isolated. Our definition of the Winnti Group is broad enough to include all these subgroups because it is based mainly on the malware and techniques they use.

Our white paper has a section describing the names we use and their aliases.

Linking supply-chain events

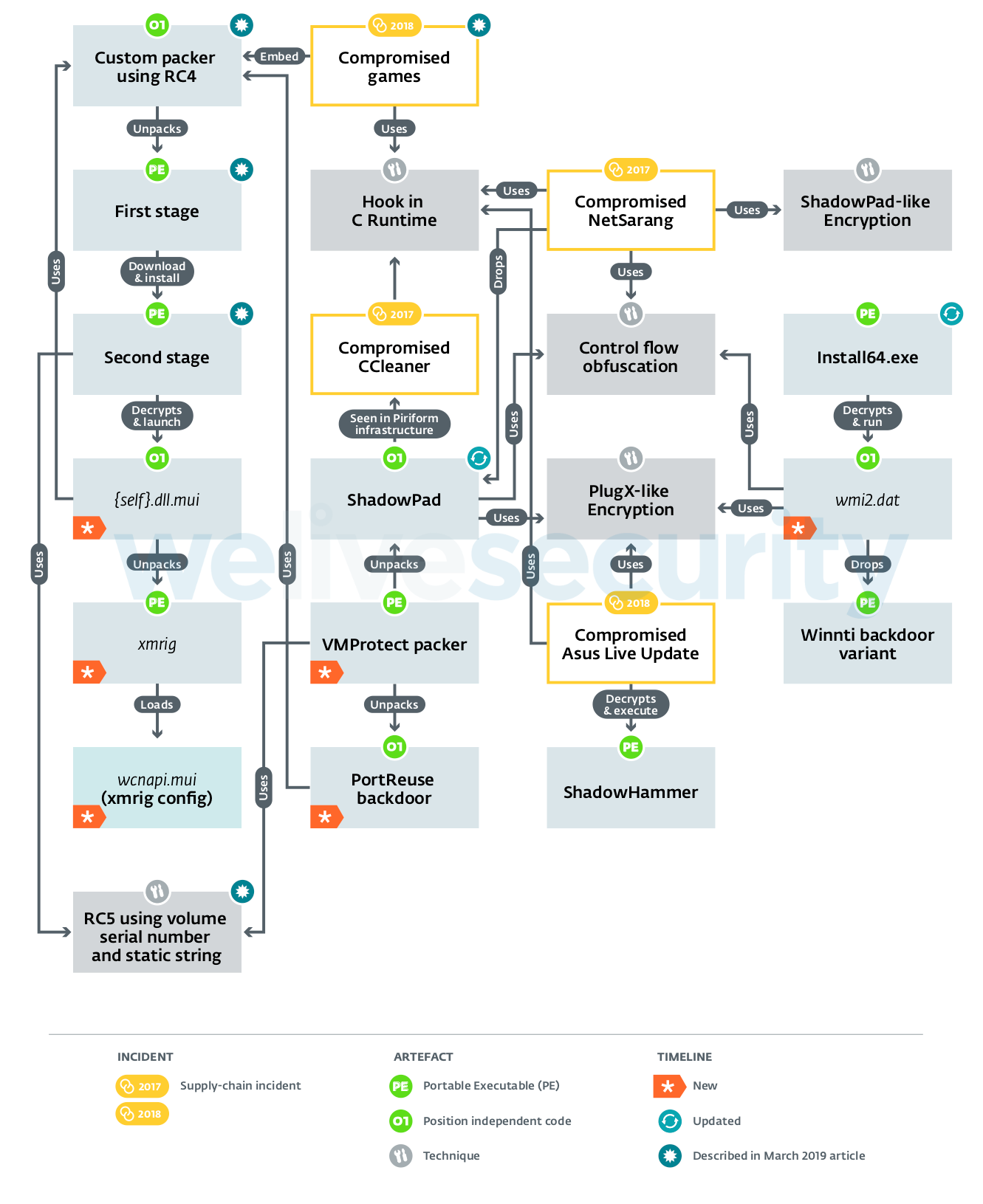

Figure 1. Overview of artefacts, techniques, events and their relationships used by the Winnti Group

We were intrigued by the unique packer used in the recent supply-chain attacks against the gaming industry in Asia. We described its structure in our previous article, and after publication, we continued the hunt to find if it was used elsewhere. The answer was positive. This packer is used in a backdoor the malefactors call PortReuse. After further investigation, we found additional samples of this backdoor with additional context confirming it is actually used in targeted organizations.

This led us on the path to find how it is deployed on compromised hosts. We’ve discovered a VMProtected packer that decrypts position-independent code using RC5, with a key based on a static string and the volume serial number of the victim’s hard drive, and runs it directly. This is exactly the same algorithm used by the second stage malware of the games compromised by the Winnti Group in 2018. There are also other ways the PortReuse backdoor is concealed, but this VMProtected packer using the same cipher and key generation technique strengthens the links between the incidents.

We’ve seen another payload delivered with the same VMProtected packer: the ShadowPad malware. ShadowPad was first seen during the NetSarang supply-chain incident, where their software was bundled with this malware. Nowadays, we see variants of ShadowPad, without the domain generation algorithm (DGA) module, in organizations targeted by the group.

Final stage of the supply-chain attack on gamers: XMRig

A few weeks after our March article was published, we were able to acquire the third and final stage of the supply-chain attack we described. Once decrypted, the payload was a custom version of XMRig, a popular open source cryptocurrency miner. This was not quite what we expected because the Winnti Group is known for its espionage operations, not for running operations that result in financial gain. Perhaps this virtual money is how they finance their infrastructure (C&C servers, domain names, etc.), but this is just guesswork.

A new backdoor used in targeted organizations: PortReuse

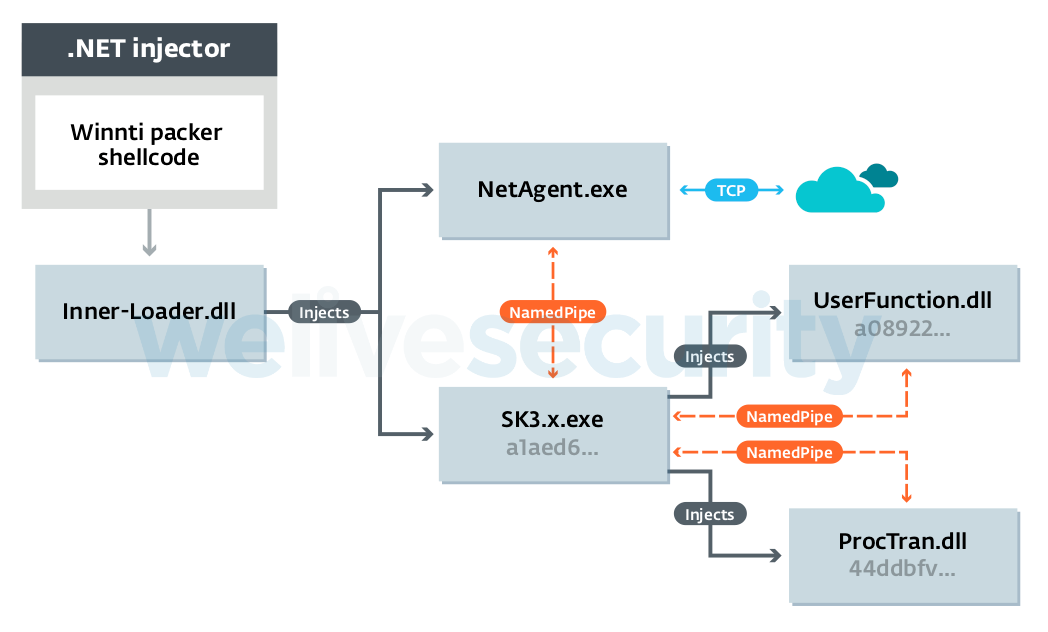

The PortReuse backdoor does not use a C&C server; it waits for an incoming connection that sends a “magic” packet. To do so, it doesn’t open an additional TCP port; it injects into an existing process to “reuse” a port that is already open. To be able to parse incoming data to search for the magic packet, two techniques are used: hooking of the receiving function (WSARecv or even the lower level NtDeviceIoControlFile) or registering a handler for a specific URL resource on an IIS server using HttpAddUrl with a URLPrefix.

There are variants out there targeting different services and ports. They include DNS (53), HTTP (80), HTTPS (443), RDP (3389) and WinRM (5985).

Thanks to Censys, ESET researchers were able to warn a major Asian mobile software and hardware manufacturer that they were compromised with the PortReuse backdoor. We worked with Censys to perform an Internet-wide scan for the PortReuse variant that injects into IIS.

More details about PortReuse's inner workings are described in our white paper.

ShadowPad update

In addition to the new PortReuse backdoor, the Winnti Group actively updates and uses its flagship backdoor, ShadowPad. One of the changes is the randomization of module identifiers. Timestamps found in each module of the samples indicate they were compiled in 2019.

ShadowPad retrieves the IP address and the protocol of the C&C server to use by parsing content from the Web set up by the attackers, and hosted on popular, publicly available resources such as GitHub repositories, Steam profiles, Microsoft TechNet profiles or Google Docs documents. It also has a campaign identifier in its configuration. Both techniques are also used by the Winnti malware family.

Conclusion

ESET researchers are always on the lookout for new supply-chain attacks. It is not an easy task: identifying small, well hidden, code added to a sometimes-huge, existing code base is like finding a needle in a haystack. We can, however, rely on behaviors and code similarity to help us spot the needle.

We were quite surprised by the final stage we found in the recent supply-chain incident in games. This group is known for its espionage capability, not for mining cryptocurrencies using their botnet. Perhaps they use the virtual money they mine to finance their other operations. Maybe they use it for renting servers and registering domain names. But at this point, we cannot exclude that they, or one of their subgroups, could be motivated by financial gain.

ESET researchers will continue to track this group and provide additional details as the team finds them. If you think you are a victim of this group or have further questions, feel free to reach out our team (via threatintel@eset.com) for additional details.

Indicators of compromise are available in our white paper, as well as on in our malware-ioc repository on GitHub.