It started, innocently enough, as a question asked in the ESET Security Forum titled "Eset – Do I Really Need Antivirus On My Linux Distros?" However, the answer to that seemingly simple question on Linux antivirus is more complex than a simple yes-or-no response.

That there's far less malware for Linux than Windows is not in doubt: A search in ESET's VirusRadar® threat encyclopedia reveals just a scant few thousand pieces of malicious software for Linux. While that may sound like a large number, ESET processes 250,000 malicious samples every day on average, releasing several thousand signatures for Windows-based malware every few days. And, of course, one should keep in mind that the term "signature" is itself very broad these days: A single signature may be able to detect multiple families of malware; while one family of malware may require tens of signatures to detect all known samples.

Yes, the threatscape out there is dominated by malware that targets Microsoft Windows, but as the world's most-widely used desktop operating system, Windows is also the most heavily-targeted.

There are many reasons that Linux doesn't have the same sorts of problem with malware that Windows has, ranging across differences in operating system security models, market fragmentation due to the multitude of distros, and its dearth of acceptance by everyday users as a desktop operating system.

But "few threats" does not mean "no threats at all." And while some of the more rabid fanatics will point out that Linux doesn't have a computer virus problem, neither does Windows today: Only about 5-10% of malware reported to ESET's LiveGrid® threat telemetry system on a daily basis is viral in nature.

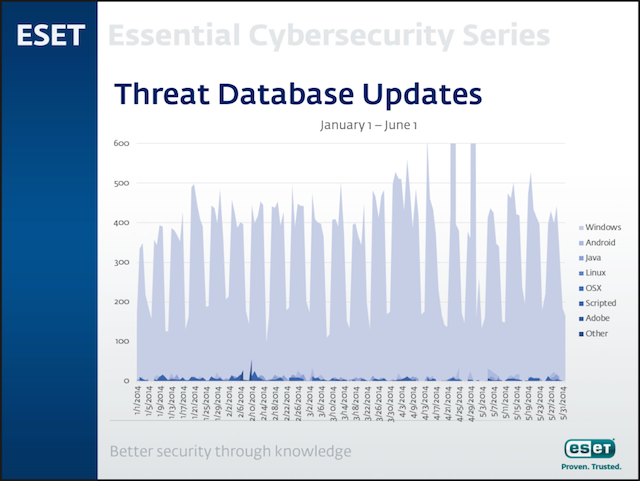

The dearth of Linux-based malware is something I had mentioned previously in the ESET 2014 Mid-Year Threat Report, which you can view here, if you have about an hour to spare. However, if you do not, here is the relevant slide from the presentation:

In case you chose not to view the entire presentation, allow me to explain what this chart means. What you are looking at represents the virus signature database updates released by ESET between January 1 and June 1 of this year. Everything that is colored light blue is some kind of Microsoft Windows-based malware—for which we commonly name with a "Win32/" prefix ("BAT/", "MSIL/", "NSIS/", "VBA/", "VBS/" and "Win64/" are also types of malware specific to Windows) when reporting its presence on the computer—everything else remaining on the chart is not. If you are having trouble viewing the non-Windows threats you may need to use your screen magnifier to zoom in a bit.

But, as the saying popularly (and incorrectly) attributed to Mark Twain goes, "there are lies, damn lies, and statistics" so treat that chart with a healthy dose of skepticism. For one thing, it does not provide any information about the amount of Linux malware detected by ESET, either in terms of absolute numbers or percentages—just the number of signatures added for each of the platforms. So, from a pure threat metrics perspective, this makes the chart less useful. But that is okay, because that is not the information I wanted to convey in the first place.

In the original presentation for which I created the chart, it was used in order to provide visibility into another metric which I thought very interesting: It serves as a kind of canary in the coal mine, an indication of the amount of effort required from ESET’s threat researchers in order to protect each platform.

While it is impossible—and misleading—to make 1:1 correlations between numeric values such as the amount of signatures and the severity of the threats they represent, looking at the volume being added on a per platform basis is an interesting metric to me, and here's why: The number of signatures being added can serve as a kind of very rough guide to how much effort is needed to protect each platform. That, in turn, provides us with a kind of mirror image, which shows how heavily attackers are targeting those platforms.

What sorts of intelligence can we can gain from such data? Well, from the look of it, it appears that in the people who are creating malicious code are expending far more effort on the creation of threats for Windows than for other platforms. And what exactly might we infer from that? The simplest answer is this activity generates the highest rate of return on their investment (writing malware). While it may seem strange, or at least counterintuitive, to bring this up in a discussion of malware, it is actually central to this discussion:

Over 99% of the malware observed by ESET on a daily basis is written for the sole purpose of supporting some kind of economically-motivated criminal activity, whether it be a (Distributed Denial of Service) attack, identify theft, spam, or plain-old robbery, albeit through somewhat newfangled methods of stealing account and transaction credentials for various financial institutions and services.

However, this is not an article about Windows-borne malware, or, at least, that wasn't the intended topic. When it comes to Linux and how it fits into criminals' online activity, the threatscape is a bit different. Linux has long been a staple of the webhosting world, and if you peer into the silver lining of cloud computing, it often looks more like Tux than, say, Clippy on the inside. This becomes even more apparent when you look at modern supercomputers: In 2014's TOP500 list, just two of the systems listed ran some version of Windows.

I would like to point out then that when I am discussing Linux, I'm referring to the various Linux distributions (or distros, for short) out there, not just the Linux kernel itself. For that matter, it would be best to extend this concept to cover not just to the distro, but the stack of software that is running on top of it, whether it be a classic LAMP stack for serving up web pages or inside networking gear moving bytes around.

A large part of the Internet runs on Linux, often far away from public view in vast data centers. Even when Linux is right in front of us, it is often invisible because it is running unnoticed on such devices as modems, routers and set top boxes. I would like to focus first, though on those data centers.

Linux is very big...

So, what exactly is it that makes Linux ideal for data center environments? Data centers consist of thousand, tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of servers, and managing that many computers rapidly becomes very challenging. Licensing costs for server operating systems vary, but Linux distros essentially start at free, although enterprises often end up paying for documentation, support and maintenance, or the costs of devoting staff to customizing it as needed.

Likewise, Linux's support of various network protocols, scripting languages and command shells—that support being typically more diverse than Windows, at least out of the box—means that it is comparatively easy and inexpensive to script management of systems. And this tends to scale well.

And then there's performance. As one of the first operating systems to originate in the Internet era, and coming from an educational rather than commercial background, Linux was designed from the ground up to connect with other systems using standard protocols such as TCP/IP. Indeed, it took Microsoft Windows server operating systems years before they could match Linux in various raw network throughput tests.

...and Linux is very small

Just as Linux scales up to very large computers, it can also be tailored to run on very small devices. Google's Android, which largely powers the smartphone and tablet industries, is based on Linux. You might find devices running Linux throughout your home: In your family room, such devices as DVRs, media players, set-top boxes and the Smart TVs in your entertainment center might be running Linux, while the broadband modem and network router that connect everything to the Internet run Linux as well. If smart, digitally-connected kitchen appliances take off, you may also be cooking with Linux one day.

Regardless of what these small devices around your home or office do, though, they have one thing in common: They don't look very much like traditional computers. They don't have keyboards, or even monitors (unless, perhaps, they are built into your monitor), and you probably access them remotely through your web browser so as to configure and manage them. If they communicate with you at all, it is perhaps with an LED light or two to let you know they're working.

The Linux Threatscape

So, what exactly are the threats facing Linux today?

Well, as previously mentioned, Linux usage tends to concentrate in two areas: The very large (data centers) and the very small (embedded in appliances and the like). In the former case, unless you work around servers all day, you may not be aware of how Linux is behind many of the most popular web sites and relied-upon services we use every day. And in the latter case, you may simply not be aware that your home router, DVR, set-top box or other "smart" home appliances are running some form of Linux. Even though both of these cases are not what we traditionally what we think of as "desktops," it does not mean they are immune to the same kinds of threats, either.

Hosted Linux servers in data centers have long been a part of the malware ecosystem, although probably not in the way most people think of it. There are many web site hosting companies out there that run outdated, insecure software and have poor system management practices. They often end up hosting command-and-control servers used by Windows-based malware to phone home for updates and instructions, serve as drop zones used by malware to store stolen information en route to the criminals who have stolen it, and so forth.

Earlier this year, ESET's researchers uncovered Operation Windigo, an attack mostly targeting Linux servers (some *BSD, Mac OS X Server and even a few Windows servers were also affected), that over the last two years affected over 25,000 servers. At first glance, 25,000 systems may not seem like a large number, given that many botnets scale to ten or thirty times that size, but when you consider that a single server might host tens, hundreds or even thousands of web sites, the actual number of end users affected by the attack was very large, indeed.

A true anecdote from my own experiences: A web forum on which I am active was affected by the Windigo campaign for many months. When I notified the site administrator that I was seeing attempts to pop up advertisements for pornography being blocked by my security software, he told me to check my Windows-based PC for viruses. It was only several months later that the hosting provider for the forum—a large web host known more for their wallet-friendly pricing than for support or security—admitted that the server on which the site was running had been compromised for the better part of a year.

At the other end of the computing spectrum, we have all of those appliances with computers embedded in them running some version of Linux. These include devices you might not necessarily think of as computers, such as Smart TVs and DVRs, as well as devices to which you may connect your computer, but do not necessarily think of as having a discrete operating system in them, such as routers, printers, NAS and so forth. We have seen numerous Smart TVs from companies such as Samsung, Philips and LG that can be taken over remotely, might spy on their users' viewing habits, or even on the users themselves via built-in webcams. And there are also worms like RBrute, which modified routers' DNS settings in order to inject ads, steal credentials and redirect search results.

Threats on the Desktop

Just as the threats targeting Linux servers are very different from those faced by embedded systems, the kinds of attacks on Linux desktops tend to vary as well.

The first thing to understand about attacks on Linux desktops is that these systems are rarely infected by malware such as worms, trojans, viruses and so forth. While this is partially due to Linux's security model, the greater reason for this is simply the lack of market penetration by Linux in the desktop space.

These days, malware is used almost exclusively for financial gain by criminals. In fact, this is so often the case these days that when malware is written for some other purpose, it becomes newsworthy simply for that reason alone. Case in point: Win32/Zimuse. When we do see malware specifically for Linux, it often seems to be written either as a proof of concept or for other research purposes, and is rarely found in the wild on customers' computers.

This, however, does not mean that Linux is immune to malicious software, especially when it comes to cross-platform threats. HTML, Java, JavaScript, PDF (Portable Document Format), Perl, php, Ruby and even SWF (Adobe Flash) are all frameworks or languages that are supported under Linux, and these can be just as easily targeted under Linux as under Windows or Mac OS X, although the underlying operating system may still be more difficult to exploit. Still, having anti-malware software installed means you can receive warning of potential threats.

Likewise, it is not unusual for Linux users to receive file attachments via email, or to be on networks with file shares, both of which can serve as vectors of malware, even if they only target Microsoft Windows. And, of course, if a Linux-specific worm such as Linux/Ramen was spreading across the network, one would want to protect one’s desktop from it. But even if the only malware on the network is targeting Windows, having anti-malware software installed can serve as a kind of "early warning" system to notify Linux desktop users that they are connected to an infected network.

As another anecdote, a friend of mine, whom I will call Richard, does exactly this. A technical writer by vocation, he switched to a Linux-only environment after some bad experiences with Windows Vista. Richard does maintain an isolated Windows XP system for occasions when he must do something in Windows that cannot be done under Linux, but, regardless of the operating system, all of his computers run anti-malware software. When people at his office accidentally send an infected file to his Linux desktop, he lets them know in the kind of clear, concise and unambiguous terms used by professional wordslingers.

Closing Thoughts

While Linux desktop systems are not magically immune to malware, they are not saturated with it either, especially in comparison to their Windows brethren. But, as both Operation Windigo and the escalating increase in Android malware have shown us, wherever a particular platform finds success, criminal elements are not far behind. While Linux on the desktop remains comparatively malware free today, that may not be the case in the future. Whether it's a requirement for compliance reasons, or simply a desire to have an ounce of prevention, anti-malware on the Linux desktop can act as a form of insurance against future attacks

For additional information about Linux-related and multi-platform malware, please see the following articles from We Live Security:

- Ongoing Web Infection (January 2008)

- Linux Tsunami hits OS X (October 2011)

- Android – meet NSA/SELinux lockdown (January 2012)

- Blackhole, CVE-2012-0507 and Carberp (March 2012)

- Apache/PHP web access holes – are your .htaccess controls really safe (July 2012)

- Malicious Apache module used for content infect: Linux/Chapro.A (December 2012)

- Malicious Apache Module: a clarification (December 2012)

- 2013 Forecast: Malware, scams, security and privacy concerns (January 2013)

- Linux/SSHDoor.A Backdoored SSH daemon that steals passwords (January 2013)

- Linux/Cdorked.A: New Apache backdoor being used in the wild to serve Blackhole (April 2013)

- The stealthiness of Linux/Cdorked: a clarification (May 2013)

- Linux Apache malware: Why it matters to you and your business (May 2013)

- Linux/Cdorked.A malware: Lighttpd and nginx web servers also affected (May 2013)

- The Home Campaign: overstaying its welcome (July 2013)

- Darkleech and the Android master key: making a hash of it (July 2013)

- Nymaim – obfuscation chronicles (August 2013)

- Ghost in the machine: Mysterious malware "jumps" between disconnected PCs, researcher claims (November 2013)

- An In-Depth Analysis of Linux/Ebury (February 2014)

- Over 500,000 PCs attacked every day after 25,000 UNIX servers hijacked by Operation Windigo (March 2014)

- Operation Windigo – the vivisection of a large Linux server-side credential-stealing malware campaign (March 2014)

- The Internet of Things isn't a malware-laced game of cyber-Cluedoe… yet (March 2014)

- Win32/Sality's newest component: a router's primary DNS changer named Win32/RBrute (April 2014)

- Windigo not Windigone: Linux/Ebury updated (April 2014)

- ESET 2014 Mid-Year Threat Report (June 2014)

- 2014 Security Lessons: Making 2015 More Secure (December 2014)

And the following podcasts, as well:

- Linux web server malware (May 2013)

- Web security for small businesses: new attacks on Linux servers (May 2013)

I would like to thank my colleagues Oliver Bilodeau, Sebastian Bortnik, Bruce Burrell and David Harley for their feedback while researching this topic.

Do you use Linux on the desktop and, if so, have you ever come across malware, either for it or another operating system? Do you also run anti-malware software on your Linux desktops? Why or why not? Let us know below!

Aryeh Goretsky, MVP, ZCSE

Distinguished Researcher