Update, 9 October 2018: The remediation section of the white paper contained inaccurate information. Secure Boot doesn't protect against the UEFI rootkit described in this research. We advise that you keep your UEFI firmware up-to-date and, if possible, have a processor with a hardware root of trust as is the case with Intel processors supporting Intel Boot Guard (from the Haswell family of Intel processors onwards).

UEFI rootkits are widely viewed as extremely dangerous tools for implementing cyberattacks, as they are hard to detect and able to survive security measures such as operating system reinstallation and even a hard disk replacement. Some UEFI rootkits have been presented as proofs of concept; some are known to be at the disposal of (at least some) governmental agencies. However, no UEFI rootkit has ever been detected in the wild – until we discovered a campaign by the Sednit APT group that successfully deployed a malicious UEFI module on a victim’s system.

The discovery of the first in-the-wild UEFI rootkit is notable for two reasons.

First, it shows that UEFI rootkits are a real threat, and not merely an attractive conference topic.

And second, it serves as a heads-up, especially to all those who might be in the crosshairs of Sednit. This APT group, also known as APT28, STRONTIUM, Sofacy and Fancy Bear, may be even more dangerous than previously thought.

Our analysis of the Sednit campaign that uses the UEFI rootkit was presented September 27 at the 2018 Microsoft BlueHat conference and is described in detail in our “LoJax: First UEFI rootkit found in the wild, courtesy of the Sednit group” white paper. In this blog post, we summarize our main findings.

The Sednit group has been operating since at least 2004, and has made headlines frequently in past years: it is believed to be behind major, high profile attacks. For instance, the US Department of Justice named the group as being responsible for the Democratic National Committee (DNC) hack just before the US 2016 elections. The group is also presumed to be behind the hacking of global television network TV5Monde, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) email leak, and many others. This group has a diversified set of malware tools in its arsenal, several examples of which we have documented previously in our Sednit white paper from 2016.

Our investigation has determined that this malicious actor was successful at least once in writing a malicious UEFI module into a system’s SPI flash memory. This module is able to drop and execute malware on disk during the boot process. This persistence method is particularly invasive as it will not only survive an OS reinstall, but also a hard disk replacement. Moreover, cleaning a system’s UEFI firmware means re-flashing it, an operation not commonly done and certainly not by the typical computer owner.

Our research has shown that the Sednit operators used different components of the LoJax malware to target a few government organizations in the Balkans as well as in Central and Eastern Europe.

LoJack becomes LoJax

In May 2018, an Arbor Networks blog post described several trojanized samples of Absolute Software’s LoJack small agent, rpcnetp.exe. These malicious samples communicated with a malicious C&C server instead of the legitimate Absolute Software server, because their hardcoded configuration settings had been altered. Some of the domains found in LoJax samples have been seen before: they were used in late 2017 as C&C domains for the notorious Sednit first-stage backdoor, SedUploader. Because of this campaign's malicious usage of the LoJack small agent, we call this malware LoJax.

LoJack is anti-theft software. Earlier versions of this agent were known as Computrace. As its former name implies, once the service was activated, the computer would call back to its C&C server and its owner would be notified of its location if it had gone missing or been stolen. Computrace attracted attention from the security community, mostly because of its unusual persistence method. Since this software’s intent is to protect a system from theft, it is important that it resists OS re-installation or hard drive replacement. Thus, it is implemented as a UEFI/BIOS module, able to survive such events. This solution comes pre-installed in the firmware of a large number of laptops manufactured by various OEMs, waiting to be activated by their owners.

While researching LoJax, we found several interesting artifacts that led us to believe that these threat actors might have tried to mimic Computrace’s persistence method.

Patching SPI flash memory with malware

On systems that were targeted by the LoJax campaign, we found various tools that are able to access and patch UEFI/BIOS settings. All used a kernel driver, RwDrv.sys, to access the UEFI/BIOS settings. This kernel driver is bundled with RWEverything, a free utility available on the web that can be used to read information on almost all of a computer’s low-level settings, including PCI Express, Memory, PCI Option ROMs, etc. As this kernel driver belongs to legitimate software, it is signed with a valid code-signing certificate.

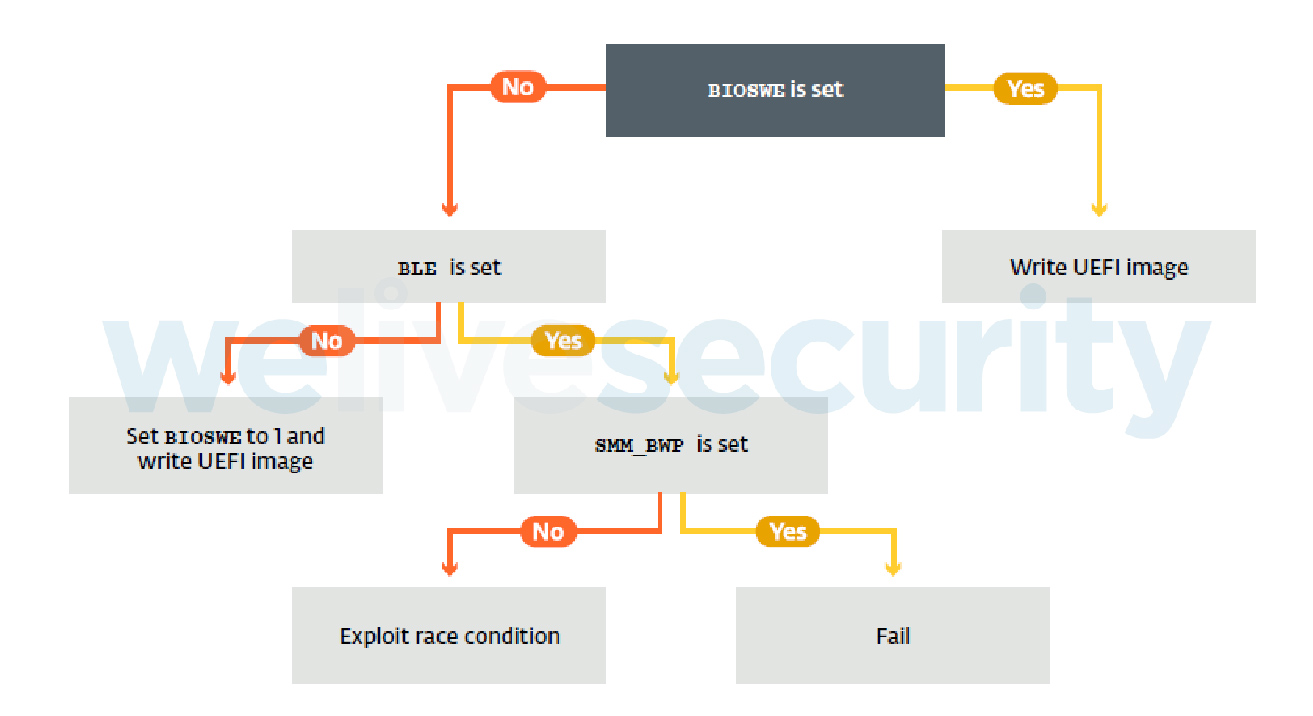

Three different types of tool were found alongside LoJax userland agents. The first one is a tool dumping information about low level system settings to a text file. Since bypassing a platform’s protection against illegitimate firmware updates is highly platform-dependent, gathering information about a system’s platform is crucial. The purpose of the second tool is to save an image of the system firmware to a file by reading the contents of the SPI flash memory where the UEFI/BIOS is located. The third tool's purpose is to add a malicious UEFI module to the firmware image and write it back to the SPI flash memory, effectively installing the UEFI rootkit on the system. This patching tool uses different techniques either to abuse misconfigured platforms or to bypass platform SPI flash memory write protections. As illustrated in the next figure, if the platform allows write operations to the SPI flash memory, it will just go ahead and write to it. If not, it actually implements an exploit against a known vulnerability.

The UEFI rootkit added to the firmware image has a single role: dropping the userland malware onto the Windows operating system partition and make sure that it is executed at startup.

How to protect yourself?

While Secure Boot is the first mechanism that comes to mind when we think about preventing UEFI firmware attacks, it wouldn't have protected against the attack we describe in this research. Despite this, we strongly suggest you enable Secure Boot on your systems, through the UEFI setup utility.

Secure Boot is designed to protect against malicious components coming from outside of the SPI flash memory. To protect against tampering with the SPI flash memory, the system’s root of trust must be moved to hardware. Such technologies exist and Intel Boot Guard is a good example of this. It has been available starting with the Haswell family of Intel processors introduced in 2013. Had this technology been available and properly configured on the victim's system, the machine would have refused to boot after the compromise.

Updating system firmware should not be something trivial for a malicious actor to achieve. There are different protections provided by the platform to prevent unauthorized writes to system SPI flash memory. The tool described above is able to update the system’s firmware only if the SPI flash memory protections are vulnerable or misconfigured. Thus, you should make sure that you are using the latest UEFI/BIOS available for your motherboard. Also, as the exploited vulnerability affects only older chipsets, make sure that critical systems have modern chipsets with the Platform Controller Hub (introduced with Intel Series 5 chipsets in 2008).

Unfortunately for the ambitious end user, updating a system’s firmware is not a trivial task. Thus, firmware security is mostly in the hands of UEFI/BIOS vendors. The security mechanisms provided by the platform need to be configured properly by the system firmware in order to actually protect it. Firmware must be built from the ground up with security in mind. Fortunately, more and more security researchers are looking at firmware security, thus contributing to improving this area and raising awareness among UEFI/BIOS vendors.

Remediation of a UEFI firmware-based compromise is a hard problem. There are no easy ways to automatically remove such a threat from a system. In the case we described above: in order to remove the rootkit, the SPI flash memory needs to be reflashed with a clean firmware image specific to the motherboard. This is a delicate operation that must be performed manually. It is definitely not a procedure that most computer owners are familiar with. The only alternative to reflashing the UEFI/BIOS is to replace the motherboard of the compromised system outright.

For more information about how to protect yourself you can visit our website and find out more about the ESET UEFI Scanner.

The links with the Sednit APT group

As mentioned above, some of the LoJax small agent C&C servers were used in the past by SedUploader, a first-stage backdoor routinely used by Sednit’s operators. Also, in cases of LoJax compromise, traces of other Sednit tools were never far away. In fact, systems targeted by LoJax usually also showed signs of these three examples of Sednit malware:

- SedUploader, a first-stage backdoor

- XAgent, Sednit’s flagship backdoor

- Xtunnel, a network proxy tool that can relay any kind of network traffic between a C&C server on the Internet and an endpoint computer inside a local network

These facts allow us to attribute LoJax with high confidence to the Sednit group.

In conclusion

Through the years we’ve spent tracking of the Sednit group, we have released many reports on its activities, ranging from zero-day usage to custom malware it has developed, such as Zebrocy. However, the UEFI rootkit component described above is in a league of its own.

The LoJax campaign shows that high-value targets are prime candidates for the deployment of rare, even unique threats and such targets should always be on the lookout for signs of compromise. Also, one thing that this research taught us is that it is always important to dig as deep as you can go!

A full list of Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) and samples can be found on GitHub.

For a detailed analysis of the backdoor, head over to our white paper LoJax: First UEFI rootkit found in the wild, courtesy of the Sednit group.