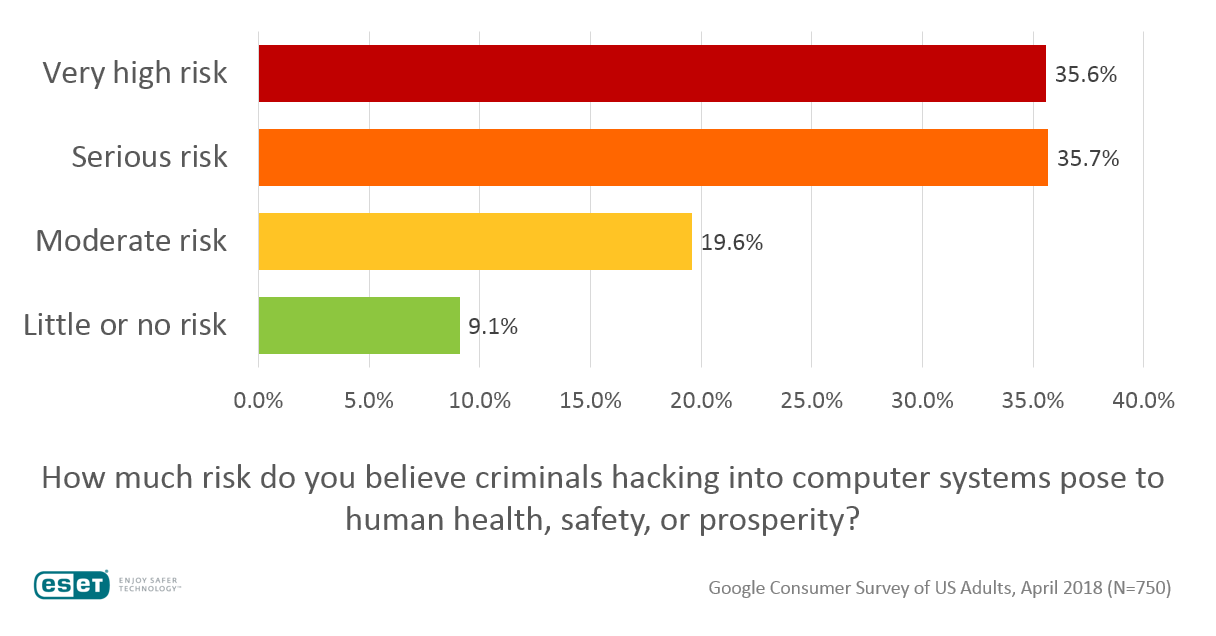

Do criminals hacking into computer systems pose a risk to your health, safety, or prosperity? If you ask US adults this question, the answer is likely to be a resounding yes! Last month we put this question to 750 people and gave them four possible answers: Little or no risk; Moderate risk; Serious risk; and Very high risk. This chart shows answers by percentage of respondents:

As you can see, over 70% said they believe that the risk is either serious or very high (35.7% + 35.6%). I think these numbers have important implications for all companies and government agencies (in particular any organization that has pinned its hopes on “digital transformation,” a topic to which I will return later in this article).

The court of public opinion

For a start, the depth of public concern about criminal hacking means that reaction to news that your organization was a victim of criminal hackers could be more negative than you might think (even though your organization was technically a crime victim).

Do not be tempted to think that, because there have been many big breaches in recent years, the public is getting used to them and is thus less bothered by them, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “breach fatigue.” I would argue that there is a cumulative aspect to the constant bad news about data insecurity and privacy violations. This means that some percentage of future criminal hacking incidents will generate “last straw” anger that surfaces despite breach fatigue.

Look at what happened to Equifax’s share price last September: it dropped from $143 to $90 in the days immediately following news of their security breach. It has not yet regained anything like its former value and is currently trading around $114.

Admittedly, the scale and nature of the Equifax breach was exceptionally egregious, but I see no reason to assume that, in the current atmosphere, your organization is going to get a free pass from consumer outrage in the wake of a data breach or other successful criminal hack of your systems.

This atmosphere includes headlines around election hacking, the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data privacy fiasco, a string of retail and hospitality industry credit card hacks, and the long tail effect of criminal justice (in which past criminal hacks generate fresh headlines due to the capture/trial/sentencing of the perpetrators).

Not just a blip

I have been tracking and assessing public opinion about cybercrime for some time now and I am familiar with the argument that surveys only capture reactions to the latest headlines. It is argued that people believe there’s lot of risk because they’ve just seen a recent scary headline, and that concerns fade over time. Well, these days the hacking headlines keep coming, and besides, the above survey was not timed to capture reaction to any particular event.

The same is true of the survey we did just over a year ago, in April 2017. We asked a question that is similar to one in the chart above: Do you think problems with technology, like computer hacking and network outages, pose a risk to your security and well-being? The answer choices were: Almost no risk, Slight risk, Moderate risk, and High risk. More than 68% of respondents chose the last two answers: Moderate (35%) and High (33.5%).

There are other supporting data points in ESET research on the topic of risk perception (see Adventures in Cybersecurity Research). Last year we found that when people were asked to rate a wide range of risks, from hazardous waste disposal to theft of personal data, criminal hacking was seen as riskiest, even though we were not looking for that result.

Something needs to be done

So here is where we are as far as I can tell: concern about criminal hacking has been getting both broader and deeper in recent years, to the point where it could seriously undermine the next stage in the world’s adoption of digital technologies, the much hyped “digital transformation.” Just in case you have somehow avoided this buzzword, here’s a fairly universal definition:

“Digital transformation is the profound transformation of business and organizational activities, processes, competencies and models to fully leverage the changes and opportunities of a mix of digital technologies and their accelerating impact across society in a strategic and prioritized way, with present and future shifts in mind.” (from i-SCOOP)

I find it hard to imagine this transformation succeeding if the general public continues to see the criminal hacking of those “digital technologies” as a serious or very high risk. And right now the governments of the world are not – I would argue – putting anything like enough resources into cybercrime prevention and deterrence. So, short of the miraculous discovery of some cheap, easy, fast, and effective technological fix for the cybercrime problem, the outlook for digital transformation remains grim, at least from where I’m sitting.

Clearly, not everyone shares my perspective. Why is that? I see two factors that obscure current reality. First, not enough people have been paying attention to the negative numbers, the indications that consumer uptake of digital technology is already being undermined. Even back in 2016, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), working with 2015 US survey data, found that 45% of online households in America were refraining from “participating in certain online activities due to privacy or security concerns”. This included activities like online financial transactions, buying goods or services online, posting on social networks, or expressing opinions on controversial or political issues via the internet (see this 2017 WeLiveSecurity article as well as this one from 2016).

The second disconnect comes from the distraction caused by growth curves – when uptake of technology is rising quickly, it is hard to see that some people are holding back. Furthermore, in all the growth-induced excitement, it is easy to overlook the fact that not everyone coming onboard is as committed to your vision of the future as you might think.

For example, think back to when the dot-com bubble burst in 2000. Some people who are building digital companies today may be too young to remember what it was like when that went down; but wow, did it go down. The tech-heavy NASDAQ index lost 78% of its value, falling to 1,114 from 5,046 — a fall from which it took 15 years to recover. The point is this: we can ill afford to risk undermining trust in digital technology by failing to address cybercrime head on.