Many countries are counting on a booming digital economy to create higher paying jobs, improve productivity, and deliver future prosperity. So these countries should be concerned by any signs that this growth is being undermined by an erosion of trust in, and growing fear of, digital technology. Because I think there are signs of this happening, I decided to ask 1,000 adults in the US the following question:

Do you think problems with digital technology, like computer hacking and network outages, pose a risk to your security and wellbeing?

I will share the results in a moment, but first a few definitions and some background. The digital economy can be defined as “the worldwide network of economic activities enabled by information and communications technologies (ICT). It can also be defined more simply as an economy based on digital technologies” (TechTarget).

Survey background

If you will pardon the pun, computers are the core of digital technology and, as the President’s Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity observed in its report to the President in 2016: “Computing technologies have enormous potential to improve the lives of all Americans. Each day we see new evidence of how transformative these technologies can be, and the ways they can positively affect our economy and our quality of life in the workplace” (The White House).

The Commission went on to say: “We live in a digital economy that helps us work smarter, faster, and more safely. Change is not limited just to our workplaces, of course. Our lives are enriched by digital devices and networks and by the innovators who have found creative ways to harness technology.”

So far, so good, but then the Commission made this critical point: “our digital economy and society will achieve full potential only if Americans trust these systems to protect their safety, security, and privacy.” Not only do I agree with this, it happens to be a reality that has been bothering me for the past two decades.

Despite the high rate of speed with which the commercial internet grew in the US in the late 1990s, it was clear to me that some people were eschewing the technology over concerns about security and privacy. There were not enough of these people to bother the tech companies that were enjoying growth curves which looked like hockey sticks, but they existed.

As the new century unfolded and cybercrime became increasingly rampant, I grew increasingly worried that the digital economy was underperforming its true potential. But it was not until the Snowden revelations of 2013 that I got a chance to measure the effect of negative news about digital privacy and security. And what I found was this: the digital economy is not immune to reversals of fortune. ESET conducted a survey in the US that asked people whether they had reduced their online activity "based on what you have learned about government surveillance". A significant percentage of respondents said that they had. We surveyed again in 2014 and found the effect was even more pronounced - about one in four people had indeed reduced their online activity in key areas.

| 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| I have done less banking online | 19% | 26% |

| I have done less shopping online | 14% | 26% |

| I am less inclined to use email | 19% | 24% |

In 2016, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), working with 2015 US survey data found that 45% of online households in America were refraining from “participating in certain online activities due to privacy or security concerns”. This included activities like online financial transactions, buying goods or services online, posting on social networks, or expressing opinions on controversial or political issues via the Internet.

Also in 2016, ESET reported that public perceptions of security and privacy risk were impacting one of the most talked about elements of a prosperous digital future, the Internet of Things (IoT). For example, 50% of US consumers surveyed indicated that concerns about the cybersecurity of an IoT device had discouraged them from purchasing one.

Survey results

Clearly, a significant number of Americans see risks in digital technology and some react to those risks by changing behavior. Yet some journalists have questioned the persistence of technology fears over time, arguing that memories of specific incidents – like the Snowden revelations or landmark data breaches like Target – tend to fade. My response has been two-fold: first, the bad news keeps coming and that tends to keep fears alive; and second, we have to keep taking the temperature of public opinion.

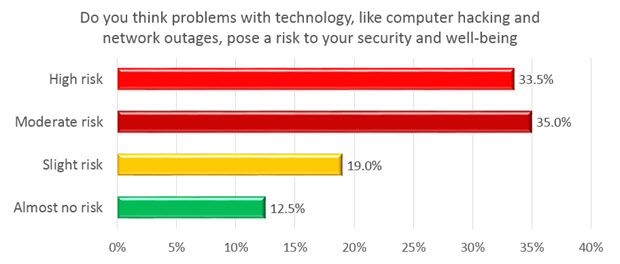

So I was very keen to see what happened when I had the chance to ask 1,000 US adults last month if they thought problems with digital technology, like computer hacking and network outages, posed a risk to their security and wellbeing. The possible responses were: Almost no risk; Slight risk; Moderate risk; and High risk. The responses were presented in that order on half the survey forms, the other half reversed the order (this was done on a random basis to reduce bias caused by answer ordering).

To be honest I expected the results would show a 50/50 split between folks who saw little risk (no+slight) and those who saw more risk (moderate+high). In fact, the survey result was closer to 32/68 in favor of more risk. Fully one third of respondents selected High risk. Moderate risk was selected by 35%.

Source: Survey conducted for ESET by Google Surveys, March, 2017

With only one in eight respondents seeing “almost no risk” and less than one in five seeing only “slight risk” it looks like the foundations of our digital future may be not as firm as many economic projections assume they are.

When I broke down the responses by age it is clear that those under 45 see less risk than those 45 or older, which tech companies might take to be ray of hope for the future. However, in my opinion, that would be a mistake. Why? Because I am firmly in the high risk camp. I think that problems with technology, like computer hacking and network outages, do pose a risk to our security and wellbeing.

Furthermore, I would argue that underestimating digital technology risks actually adds to them. Now is not the time to spell out that argument, but it is a subject to which I will return. My colleague Lysa Myers and I are going to carry out a more detailed survey of public perceptions of digital technology risk later this year. We will also examine the implications of those perceptions for the digital economy.

In the meantime, it is clear that, justified or not, a lot of people in the US think problems with digital technology, like computer hacking and network outages, do pose a risk to their security and wellbeing.