This is the second part of a two part look at research exploring risk perception, particularly with respect to digital technology risks like the theft of valuable data, unauthorized exposure of sensitive personal information, and unwanted monitoring of private communications; in other words, threats that cybersecurity professionals have been working hard to mitigate. (Part one is here.)

The story is in two parts because it turned out to be longer than expected. Here is the TL;DR version of the whole story:

- The security of digital systems (cybersecurity) is undermined by vulnerabilities in products and systems.

- Failure to heed experts is a major source of vulnerability.

- Failure to heed experts is a known problem in technology.

- The cultural theory of risk perception helps explain this problem.

- Cultural theory exposes the tendency of some males to underestimate risk (White Male Effect or WME).

- ESET researchers have assessed the public's perceptions of a range of technology risks (digital and non-digital).

- Their findings provide the first ever assessment of WME in the digital or cyber realm.

- Additional findings indicate that cyber-related risks are now firmly embedded in public consciousness.

- Practical benefits from the research include pointers to improved risk communication strategies and a novel take on the need for greater diversity in technology leadership roles.

Cyber risk research

When considered in the context of digital technology and information systems, risk has been defined as “the probability that a particular threat-source will exercise (accidentally trigger or intentionally exploit) a particular information system vulnerability” (see Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems NIST Special Publication 800-30). This suggests that one way to reduce cyber risks would be to reduce the number of vulnerabilities, such as those produced by the three sources noted in part one, each of which can be framed as people and/or organizations not heeding expert advice about the level of risk involved in digital technology.

"Also interesting is that non-white males pretty much concur with their white counterparts on the rating for this risk, and that of criminal hacking"

Armed with the cultural theory described in part one as a possible explanation for why some people do not heed expert advice, we fielded a survey that queried US adults about their attitudes to 15 different technology hazards, including six that were cyber-related. To conduct our research, we created something called “The Technology Sentiment Survey.” Consisting of a website and an online form, this survey was intentionally designed to appear neutral so there was no obvious corporate or institutional affiliation. Furthermore, in order to avoid skewing participant responses, the survey was not positioned as a risk study. The survey was introduced to participants like this: “Exploring how we feel about various technologies today has the potential to improve the ways we manage them in the future.”

To enable comparisons with results from other surveys, this project adapted, with permission, two sets of questions used in previous academic studies of risk perception. To obtain a cultural theory perspective on respondents we used the “Cultural Cognition Worldview Scales”. To gauge risk perceptions we used the “Industrial Strength Risk Perception Measure” (ISRPM). Both were provided to us by Prof. Dan M. Kahan of the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale Law School, to whom we are indebted, not only for his informal guidance on survey design but also for his pioneering work in this.

Here is how the risk perception questions were framed, using the language of the ISRPM:

As individuals and as a society, we face a number of possible hazards. Some threaten people’s health, safety, or financial well-being directly. Others indirectly threaten health, safety, or financial well-being through the damage they can impose on the environment or the economy. The next set of questions asks how much risk you think the following items pose to human health, safety, or prosperity. In each case you can answer from "No risk at all" to "Very high risk.”

The questions were then presented individually, one per page, for example: “How much risk do you believe global warming poses to human health, safety, or prosperity?” The order in which the hazards were presented was randomized. Here are the 15 items:

Non-digital technology hazards |

Digital technology hazards |

|---|---|

| Air pollution | Theft or exposure of private data |

| Disposal of hazardous wastes in landfill sites | Criminals hacking into computer systems |

| Medical X-rays | Companies accumulating your personal data |

| "Fracking" (extracting natural gas by hydraulic fracturing) | Government monitoring of citizens' emails and web searches |

| Nuclear power | Artificial intelligence |

| Motor vehicle accidents | Corporate computer network failures |

| Global warming | ~ |

| Genetically modified foods | ~ |

| Private gun ownership | ~ |

Note: In the following charts of survey results some names are shortened and PII is used for private and personal data.

We fielded the survey online during the summer of 2017 using the SurveyMonkey Audience of US adults. In terms of cyber-related events, the timing was after the WannaCryptor (aka WannaCry) and Diskcoder.C, (aka NotPetya) malware outbreaks, but before the Equifax breach. More than 700 people completed the survey. Of these, 45% were male and 55% were female. Three quarters of respondents identified as white. The age breakdown was 21% age 18-29, 25% age 30-44, 30% age 45-59, and 25% age 60 and over. More than half of respondents (53%) were in full-time employment.

(Note that for convenience of presentation, the survey results shown in the following charts refer to personal data and private data as PII, which is shorthand for Personally Identifiable Information, which has a specific legal meaning in some contexts but is used more loosely here.)

Surprising results

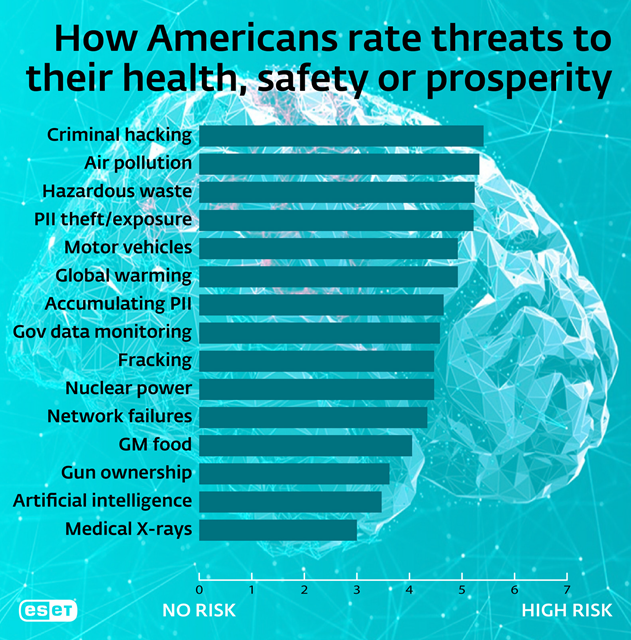

As soon as the survey responses came in, one finding jumped out: criminal hacking was rated as the greatest risk overall, ahead of global warming, air pollution, and disposal of hazardous waste in landfills. Other cyber-risks, like theft or exposure of private information, also registered strongly relative to non-cyber risks in the survey. This result, the relatively high rating of cyber risk, prompted ESET to issue a press release featuring the chart seen in Figure 6:

You might ask if this finding was truly noteworthy, given how much press criminal hacking has received in recent years. As a security professional I would have to say it was notable, and remains so, and here is why: to the best of my knowledge, this is the first time cyber risks have been assessed alongside non-cyber risks in a standardized format using a decent sample size (n=740).

Of course, there have been plenty of surveys showing people are concerned about cyber-related issues. When ESET asked 390 US adults last year “Do you agree that America is currently experiencing a cyber crime wave?” almost 70% agreed. That same year, we found 60% of Americans agreed that “The federal government is not doing enough to catch and prosecute people who commit computer crimes.” More recently, Gallup found that Americans worry about cybercrime more often than other crimes. Even more recently we ran a Google Survey of 800 US adults and seven out of 10 respondents agreed that problems with technology, like computer hacking and network outages, posed a risk to their security and well-being.

So yes, it is significant that this risk research survey found Americans perceive “criminal hacking” to be a greater risk to their health, safety and prosperity than other significant hazards, including climate change and hazardous waste disposal. For example, the weighted average score for the risk that “global warming poses to human health, safety, or prosperity” was 4.92. The corresponding score for “criminals hacking into computer systems” was 5.41.

Broader findings

The following table shows all the hazards we asked about, listed by weighted average risk score and top two box score (the percentage of respondents who rated hazards in the top two categories: “high risk” and “very high risk”). Both measures show roughly the same results, although global warming, nuclear power, and government monitoring would move higher based on box score.

Rating |

Hazard |

Average |

Top 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Criminals hacking into computer systems | 5.41 | 54.6% |

| 2 | Air pollution | 5.33 | 53.8% |

| 3 | Disposal of hazardous wastes in landfill sites | 5.24 | 52.3% |

| 4 | Theft or exposure of private data | 5.22 | 48.9% |

| 5 | Global warming | 4.92 | 50.1% |

| 6 | Motor vehicle accidents | 4.92 | 42.8% |

| 7 | Companies accumulating your personal data | 4.65 | 34.2% |

| 8 | Government monitoring of citizens' emails and web searches | 4.58 | 38.0% |

| 9 | Nuclear power | 4.47 | 35.6% |

| 10 | "Fracking"(extracting natural gas by hydraulic fracturing) | 4.47 | 33.5% |

| 11 | Corporate computer network failures | 4.34 | 25.9% |

| 12 | Genetically modified foods | 4.05 | 29.3% |

| 13 | Private gun ownership | 3.62 | 25.6% |

| 14 | Artificial intelligence | 3.47 | 17.3% |

| 15 | Medical X-rays | 3.00 | 7.3% |

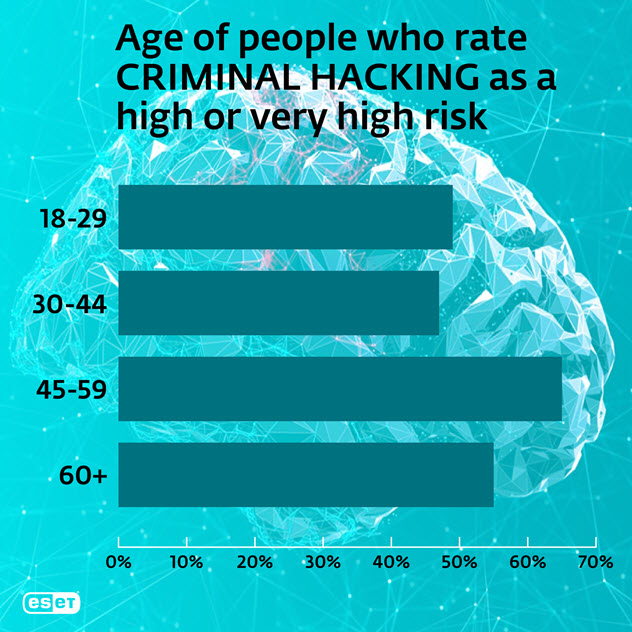

Using standard quantitative methods we found significant demographic differences in the perception of cyber risk. For example, the perception of the risk of criminal hacking varies by age. Respondents under 45 years old tend to see less risk in criminal hacking than those who are 45 or older. In Figure 7 you can see a graphical breakdown:

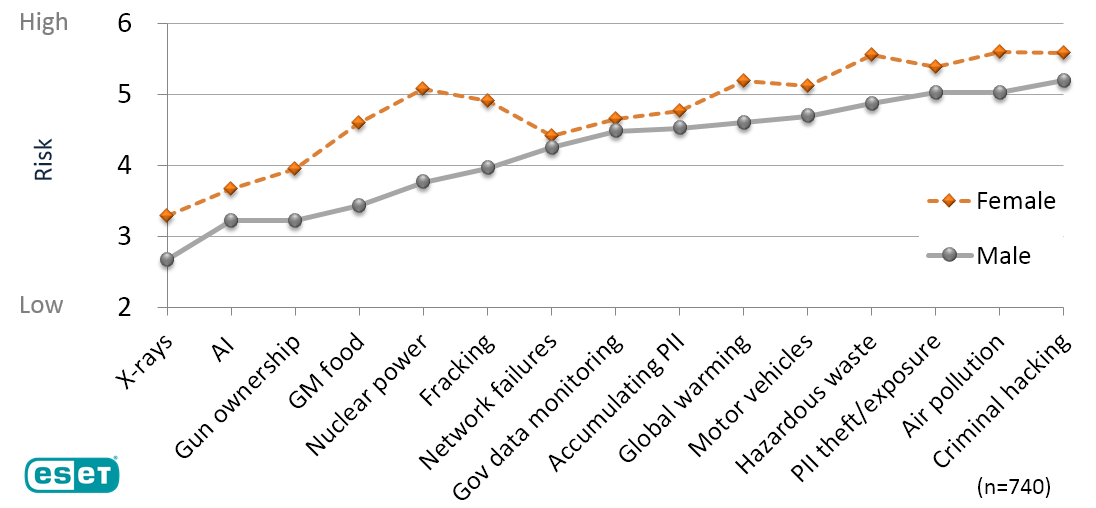

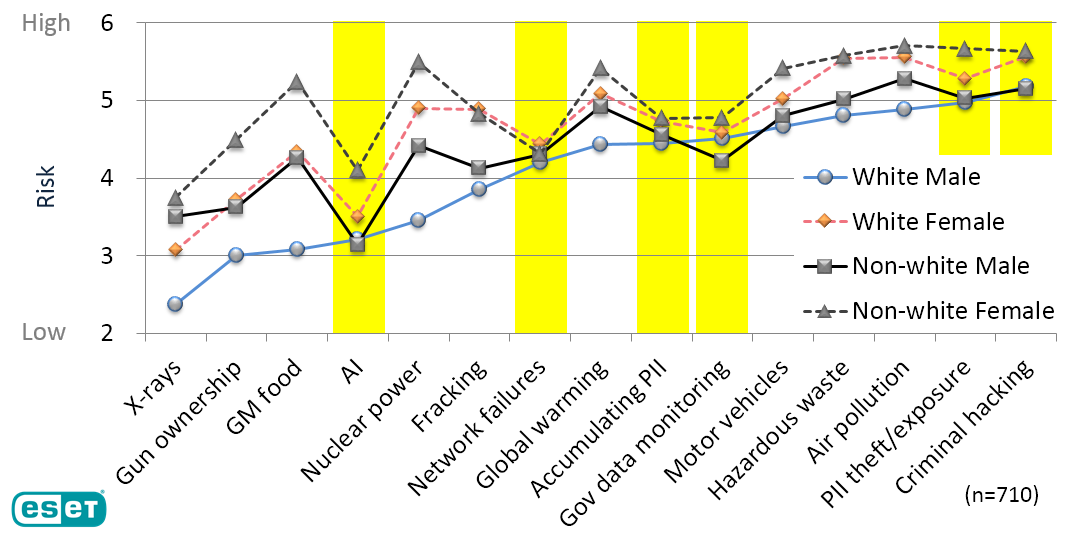

Income also affects risk perception: respondents with household income under $75,000 tend to rate the risk of criminal hacking as high or very high more often than those with household income above that (58% versus 48%). As expected, there was also a gender gap. Based on weighted averages, women saw 8% more risk than men for criminal hacking (but 14% more risk for hazardous waste disposal and 24% more risk for fracking). In Figure 8 you can see a gender breakdown for all risks surveyed:

Note the narrow gap in the middle which suggests a negligible gender-based risk perception gap for three cyber-related hazards: network failures, government monitoring of private data, and commercial accumulation of personal data. The risk scores are also relatively close for criminal hacking and theft or exposure of personal data.

The white male effect in cyber

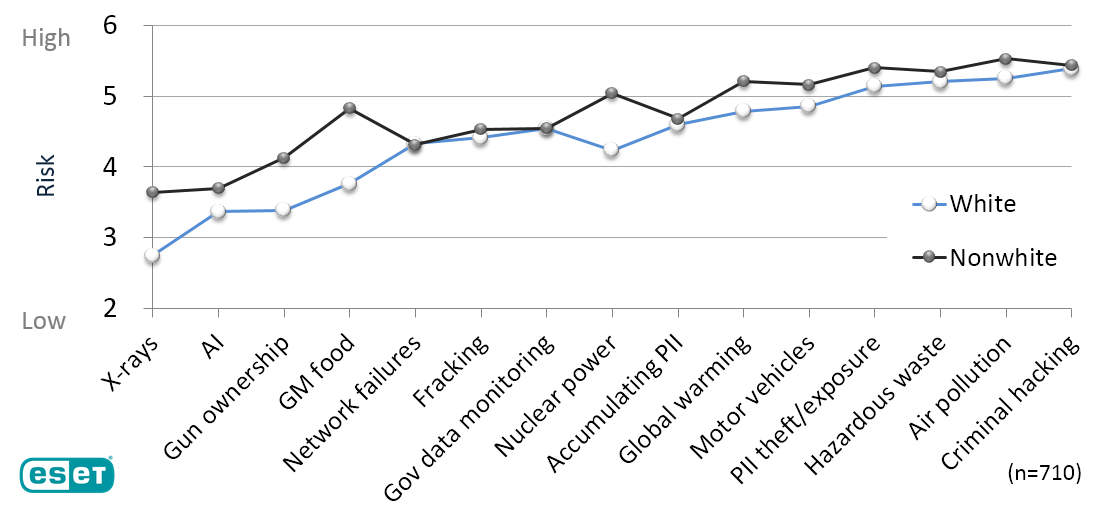

A more surprising finding was that the divergence of risk perception based on ethnicity was less pronounced than the gender gap. As you can see from Figure 9, risk scores were practically identical for network failures, government monitoring of private data, commercial accumulation of personal data, and criminal hacking.

While no causal relationships can be proven from a survey like this, there would appear to be an element of what might be termed “ethnic neutrality” when it comes to the risks posed by digital technology. This is perhaps surprising in the context of the various examples of “digital divide” that have been widely studied in recent years (see Pew Research Center reports). Could it be that, while the benefits of digital technology are not experienced universally, the risks are? This warrants further research.

Having looked separately at variations in risk perception based on gender (male/female) and then ethnicity (white/non-white), these factors were combined to show variations by gender within a basic ethnic split (white male/non-white male/white female/non-white female). In this way it is possible to detect any White Male Effect or WME, as discussed in the first part of this article.

(To recap briefly: WME is the tendency of white males to under-estimate some risks relative to the mean; multiple studies have observed this effect “in the aggregate” meaning that while some white males may rate a particular risk as serious, a larger subset may drastically under-estimate that risk; for example, most climate scientists are white males who see far more risk than do white males as a whole.)

The graph in Figure 10 charts all four categories and you can see that, although all males tend to rate risks from technology lower than all females, and all whites tend to see less risk than all non-whites, there is less disparity around digital technologies (highlighted by the yellow bars).

The survey found “classic” white male effect around gun ownership and nuclear power, but also some convergence of perception on network failures and PII accumulation. There is even one risk – government data monitoring – for which the white male rating is notably not the lowest. Bear in mind that this chart was produced by displaying the risk ratings in the order of severity perceived by white males. When seen this way, the data shows that white males rate theft or exposure of private data as the second highest risk, versus the sample average rating of fourth. Also interesting is that non-white males pretty much concur with their white counterparts on the rating for this risk, and that of criminal hacking.

Taken together, these finding suggest that white male effect is not as pronounced for digital technology risks – those addressed by cybersecurity – as it is for other technology risks. Furthermore, some risks, like criminal hacking, reflect an ethnically neutral male effect.

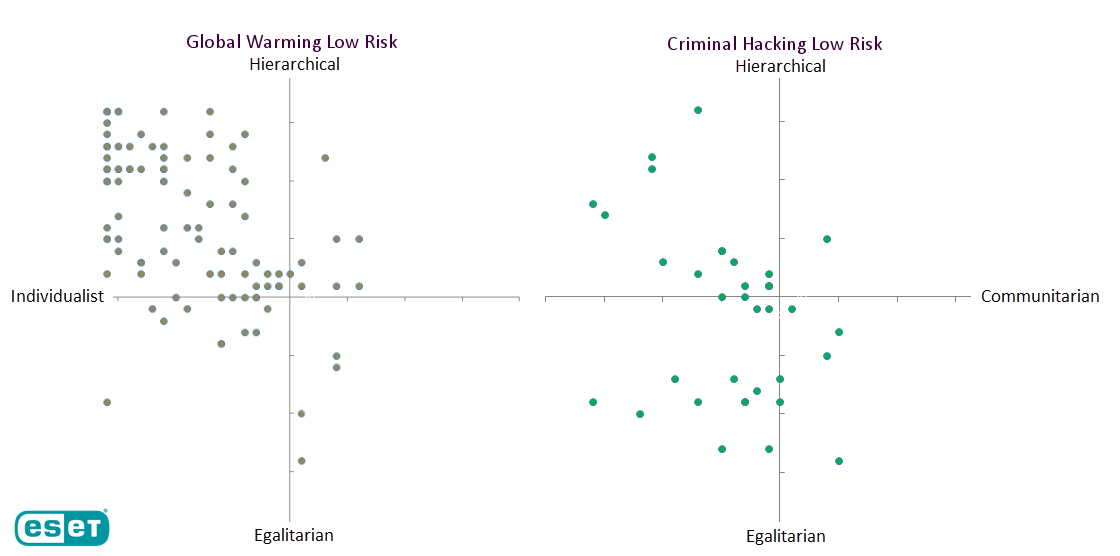

Earlier it was noted that past research has shown the white male effect to be unevenly distributed. Some white males greatly under-estimate risk relative to the mean. In the current survey results, the percentage of respondents that fell into the upper-left quadrant of the group-grid, was 26% male, 12% female. In other words, the hierarchical individualists were predominantly male, and most of the respondents who rated the risk of global warming as low were hierarchical individualists, as seen on the left-hand chart in Figure 11. This maps people who rated the risk from global warming as low.

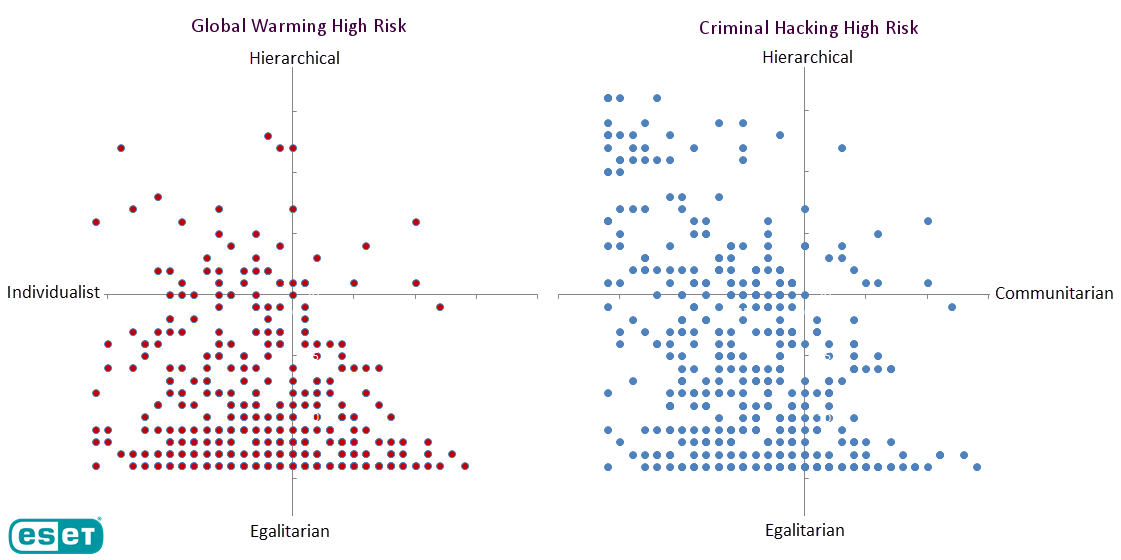

The right-hand chart in Figure 11 shows the contrast with people who rated the risk of criminal hacking as low. As you can see, they are more widely dispersed on the cultural grid. In terms of cultural distribution, the difference between the two risks is also apparent when the opposite ratings are shown, as in Figure 12 below, where “global warming is a high risk” respondents are plotted on the left, and “criminal hacking is a high risk” are plotted on the right.

Clearly there are quite a few hierarchical-individualists concerned about criminal hacking, suggesting that there is broad perception of this level of risk across multiple hierarchical alignments. This warrants further research.

Improving cyber risk communication

It is now time to ask: what are the practical implication of these results? The main benefit of this and other risk studies may well be in the field of risk communication, more specifically: improving the effectiveness of risk communication. A lot of work in this area is being encouraged and discussed by the Cultural Cognition Project, a group of scholars interested in studying “how cultural values shape public risk perceptions and related policy beliefs”. The project defines cultural cognition as “the tendency of individuals to conform their beliefs about disputed matters of fact…to values that define their cultural identities” (CulturalCognition.net).

Some researchers are studying communication improvements obtained by presenting information “in a manner that affirms rather than threatens people's values” (Cohen). Others are looking at the benefits of ensuring that sound information is vouched for by a diverse set of experts, and at reducing the polarization of risk perceptions by presenting advocates with diverse values on both sides of the issue (Kahan).

Exploring cultural theory research clearly offers practical benefits. For example, if you are trying to change the minds of people who think global warming poses little risk, how do you identify them? If you use cultural theory’s group-grid as your guide, many of these “low risk” folks can be identified (as noted earlier, most of them are in the hierarchical-individualist quadrant). Your efforts to get them to see global warming as a greater risk than they currently do can then be tailored to their cultural alignment, rather than threatening it.

What emerged from studying cyber risk from a cultural theory perspective is that people who think criminal hacking is a low risk are spread widely across the cultural alignment map (they tend to be individualistic but their precise cultural alignment varies quite a bit). However, this does not mean that cultural theory cannot assist cyber risk communication. Simply being aware of the group-grid construct and the strong tendency of people to interpret information in a way that supports their world view can be of benefit in practical risk communication scenarios.

Consider a company that hires a new CISO (Chief Information Security Officer). She immediately performs a data audit and risk assessment, but when she presents it to the board of directors and requests additional funding to implement what she sees as essential security measures, she gets pushback and realizes that they don’t think the risks are as great as she does. The situation requires risk communication that is effective for this audience, and by considering the cultural alignment of board members the CISO can craft her message accordingly.

Issues, observations, and next steps

This research project has shed new light on cyber risk perceptions. It revealed that people see a relatively high level of risk in a range of hazards associated with our use of digital technologies, notably criminal hacking, which was rated a greater risk than “traditional” technology hazards such as toxic waste disposal and global warming. Furthermore, the cultural alignment of cyber risk was shown to be quite different from that of global warming, suggesting that concerns over cyber-related hazards are shared quite broadly.

The study did detect the tendency of white males to see less risk in technology in general, although this white male effect was less evident with respect to cyber risks. Indeed, white males appeared to be particularly sensitive to theft or exposure of private data and government monitoring of citizens' emails and web searches. The risk perceptions of survey respondents definitely diverged along gender lines. Women saw more risk than men in all 15 hazards, although the narrowest gaps were cyber-related: network failures, government monitoring of private data, and commercial accumulation of personal data.

"The risk perceptions of survey respondents definitely diverged along gender lines"

Of course, this is just one study, and if this was an academic journal article it would require the recitation of a bunch of caveats and disclaimers. Suffice to say, the author is well-aware of the study’s limitations, such as sample size, sampling method, and the dangers of generalizing from these findings to the whole population. Clearly, there is a need for a larger survey, and preferably multiple larger surveys. Hopefully, this article has made a good case for additional research on this topic. To that end, the author is happy to share the survey instrument with other researchers.

The author is also aware of the criticisms levelled at cultural theory, such as the claim that it is overly US-centric. I encourage researchers in other countries to replicate this study and again, the survey instrument can be made available to them.

Clearly, many factors may influence a person’s perception of risk, not just their cultural alignment (although several studies that controlled for other factors did find cultural alignment to be the strongest determining factor in risk perception). There are also multiple explanations as to why people’s minds are hard to change and what that can tell us about our efforts to influence others, for example to convince them not to click on dodgy email attachments. The applicable areas of research include cognitive neuroscience (for an accessible account, see Sharot’s The Influential Mind).

To the extent that broad implications can be derived from the current, limited research, I would suggest that one in particular is worth considering. When I discussed the cultural theory of risk perception in a TEDx talk I said that one possible implication of the white male effect was this: greater diversity in tech industry leadership roles could lead to a reduction in the number of vulnerabilities open to exploitation by bad actors and, in turn, this could relieve some of the pressure on the currently over-extended cybersecurity profession. The logic of this assertion is that women and minorities tend to be more sensitive to risk and, if they were better represented in key decision-making roles in companies they would moderate the white male effect. While this current study hints that the disparity in risk assessment in the cyber realm might be more of a male effect than a white male effect, more extensive research, with a focus on upper management in the tech industry, should prove enlightening.