Here is a good essay question for students of cybersecurity and public policy: “Does the government jeopardize internet security by stockpiling the cybervulnerabilities it detects in order to preserve its ability to launch its own attacks on computer systems?”

This question is also at the heart of several documents published today by the US government. If this question interests you then I suggest you read all three of them:

- Improving and Making the Vulnerability Equities Process Transparent is the Right Thing to Do

- This is a statement articulating the problem of what to do with software vulnerabilities discovered by government agencies, as well as the government's current position, posted on the WhiteHouse.gov website by Rob Joyce, the White House Cybersecurity Coordinator

- Vulnerabilities Equities Policy and Process for the United States Government

- This 14-page unclassified PDF describes the Vulnerability Equities Policy (VEP) in some detail

- FACT SHEET: Vulnerabilities Equities Process

- This handy 3-page summary includes a listing of the Defensive Equity Considerations

Welcome transparency and articulation

Before I comment on the US government’s policy around the handling of software vulnerabilities discovered by its agencies – the pros and cons of getting them fixed or letting them be exploited – I want to take a moment to applaud today’s move to shed light on what that policy is (its official name is the Vulnerability Equities Policy or VEP).

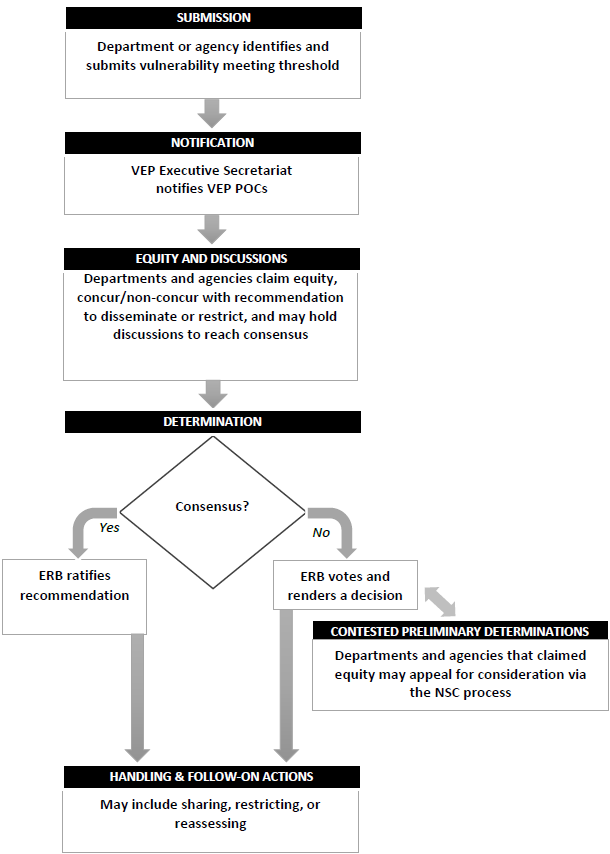

The statement by Rob Joyce is a very helpful articulation of the complex challenges and dilemmas surrounding this issue, and to be clear: it’s a very complex issue. For that reason I was very pleased to see that the process for making decisions about keeping vulnerabilities secret, described in the other two documents, reflects an awareness of the need for, and a willingness to consider, multiple perspectives. That is illustrated in the flowchart shown here and described in the Vulnerabilities Equities Policy and Process

for the United States Government document released today (PDF):

How this works in practice is not something about which I have any inside information. However, like many other security researchers, I will be keeping an eye out for any hints that might be dropped by folks who work with the VEP process. I certainly appreciate the service of those men and women who are tasked with handling this very daunting problem.

Policy versus practice

I also appreciate that the White House Cybersecurity Coordinator is aware “there are advocates on both sides of the vulnerability equity issue who make impassioned arguments.” While I’m pretty sure that, at the end of the day, my views do not align with those of Mr. Joyce, I do appreciate his efforts to inform the public about the rules by which the government is operating.

If you happened to read my comments in the WeLiveSecurity article announcing the publication of these VEP documents, you will already know that I am not happy with a government agency that finds an exploitable flaw in a widely used piece of software then deciding not to tell the maker of that software right away. While I fully understand the arguments for “hoarding” vulnerabilities so as to exploit them in the pursuit of information that could help the government defend us, my concern is that the government does not, in my opinion, fully grasp how risky this strategy is.

For evidence of that risk we need look no further than the massive WannaCryptor/WannaCry malware outbreak. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of damage were caused by exploiting a vulnerability hoarded by the US National Security Agency (NSA). How? The bad guys used an exploit of that vulnerability which the NSA itself had created, but which it failed to keep secret.

In other words, until the ability of a super-secretive agency to keep secret vulnerabilities secret is absolute, there is a strong argument to be made that the government’s duty of care to society would be better served by working with industry to fix all vulnerabilities as soon as they are discovered.

No good malware?

The response of Joyce and others to that argument is that immediate disclosure and fixing of every vulnerability “is tantamount to unilateral disarmament”. As it happens, I am a big fan of disarmament. And while it might sound presumptuous, I would liken my enthusiasm for cyber-disarmament to that of the nuclear scientists who campaigned for nuclear disarmament.

Although my personal – and some might say peculiar – views on cyber-disarmament are not shared by all cybersecurity researchers, many of us do share a deep skepticism about government engagement with information system vulnerabilities and their exploitation. After all, the exploitation of vulnerabilities is what malicious code or malware is all about, and our skepticism is fueled by frontline experience fighting the deleterious effects of malware on organizations and individuals. That is a battle that has been waged every day for decades.

A few years ago my colleague Andrew Lee and I tried to sum up the collective wisdom of antimalware researchers on this topic in a paper titled “Malware is called malicious for a reason: the risks of weaponizing code.” It was presented at CyCon, the annual NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence conference, a great event at which to engage in cyber policy debates. While we did not address the hoarding of vulnerabilities specifically, we did lay out the risks of engaging in the development and deployment of “righteous malware,” including the practical impossibility of any nation or other entity keeping such weapons to itself.

It is no secret that the NSA has now come face to face with that impossibility. The question of what should be done about that is currently unanswered, although an authority I respect, James Bamford, has forcefully advocated stringent measures. Also unanswered is the question of how much relief the victims of government-enabled malware can get from the government that, through its hoarding of vulnerabilities, enabled it.

Let us hope that participants in the Vulnerability Equities Process will bear these questions in mind.