Code signing certificates are used to authoritatively identify a software publisher and to guarantee that the content signed with the certificate has not been tampered with between the time it was signed and the time the user executes it. Unfortunately, we see more and more malware signed using fraudulently obtained or stolen code signing certificates. We recently witnessed such a case with a series of malicious binaries, all signed with the same digital certificate. This blog post will present some background on the signing certificate involved as well as a technical analysis of two distinct malware threats written by the author of this operation.

Digital certificate

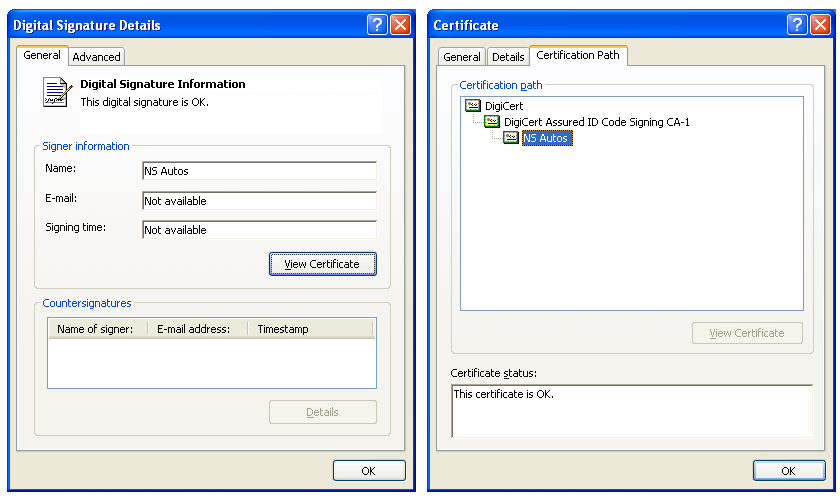

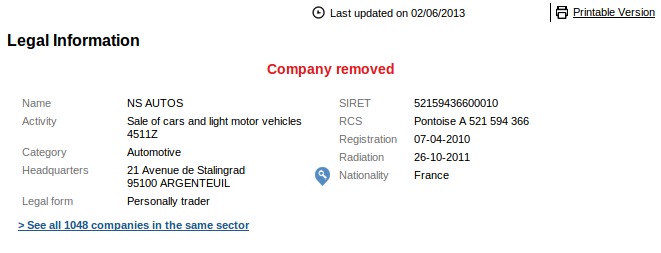

The digital certificate used in this campaign was issued on November 19, 2012 by DigiCert to a company named "NS Autos". According to www.societe.com, a company running by that name briefly existed in France, but was dissolved in 2011, way before the digital certificate was issued.

We searched our entire sample database looking for all the binaries signed by this particular digital certificate. We found a total of 70 different files. Time to do some serious work.

Most of the files were written in .NET and perform several different types of malicious activities. There were droppers, downloaders, a screen locker and a banking Trojan. We have also found samples of Win32/Remtasu and Win32/Zbot. Win32/Remtasu is a Trojan that steals sensitive information, notably using a keylogger.

Analyzing the .NET samples made it obvious that they were all written by the same person, as the coding style is the same and variable names and classes are re-used across different assemblies. Looking at the code, it is quite obvious who wrote it and we were able to track his actions in many places across the web. After researching the virtual identity of this malware author, it appears that he originates from the Maghreb. One can see a progression in his creations and some refinement of his methods.

Sample analysis

We present analysis of two examples of this malware author's work.

MSIL/Spy.Labapost.A

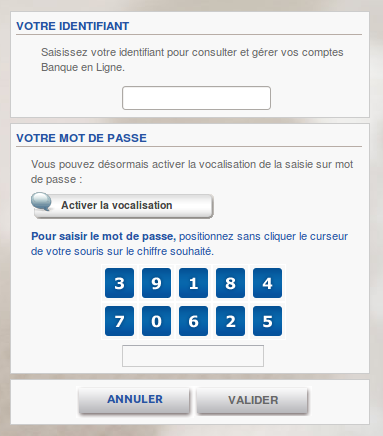

The first sample we will look at is a Trojan with Man in the Browser and webinject functionality. This sample is targeting a French bank and tries to fraudulently transfer money by automatically adding a money transfer recipient and stealing the account credentials.

Although the methods used to steal money from compromised accounts are not new, we don’t see them often in malware coming out of the Maghreb. Attacks on francophone bank users hailing from this region have historically been more focused on phishing attempts than banking Trojans [1]. Of course, they benefit from an additional advantage as they speak French fluently. Let’s take a brief look at the functionality of this Trojan.

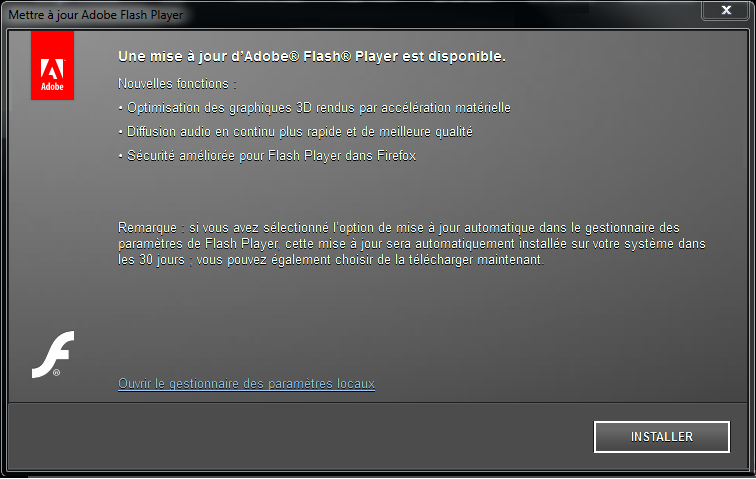

The dropper for this Trojan tries to install itself on the system by mimicking an adobe Flash Player update:

This technique is widely used and was seen in the infamous OSX/Flashback. Once the malware is installed on the system, it will periodically monitor browser processes. Once it detects that the user is browsing the targeted bank webpage, it will kill the browser window and open a .NET browser inside a new window.

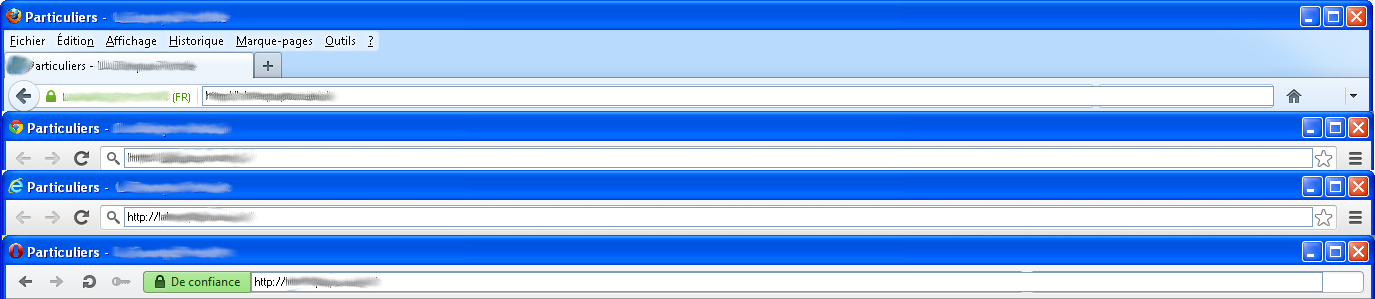

Implementation wise, it uses the .NET WebBrowser class to allow the user to browse the web inside a form. This new form is trying to spoof the browser skin through an image, trying to make the user believe that he is still in his browser. All menu items and even the navigation bars are there just for the looks, no menus or buttons are actually working. Once this is in place, the user is effectively browsing its bank account in a browser totally controlled by the attacker. Opera, Internet Explorer, Chrome and Firefox have their own skins implemented.

As one can see from the stacked screenshots, the malware author didn’t make much effort with the Internet Explorer skin, just reusing the Chrome one. Once the fake browser is started, a video capture process using Hycam2 is started. This is done to capture the user PIN as it must be entered through an onscreen numeric keypad.

As one can see from the stacked screenshots, the malware author didn’t make much effort with the Internet Explorer skin, just reusing the Chrome one. Once the fake browser is started, a video capture process using Hycam2 is started. This is done to capture the user PIN as it must be entered through an onscreen numeric keypad.

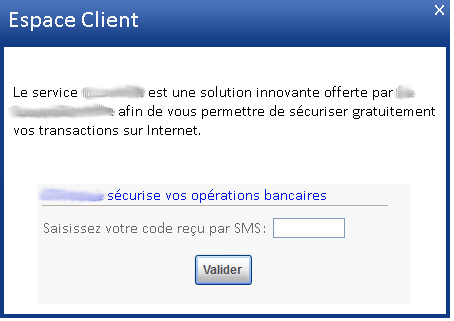

As soon as the user accesses his account, a second browser will be started and will automatically try to add a new money transfer beneficiary. The new recipient information, such as his account number, country and name, are downloaded through an external server using a GET request. As an extra security measure, the targeted bank can ask for a SMS-sent passcode before adding a new recipient. To bypass this security measure, the malware presents an input form to the user, trying to get the code the user just received on his mobile.

Once this is completed, the credentials harvested in the first step, as well as the compressed captured video, are sent to the malware author through FTP or mailed to a Gmail address. The overall coding techniques of this malware is not on par with what we usually see in the banking Trojan scene, but some of the features that are proven to work, such as Man-in-the-Browser and webinjects, are nevertheless present. Maybe the author was inspired by some of the major banking Trojans that implement these functions such as Win32/Zbot.

Once the new recipient is added, the criminal can later log back in with the leaked credentials and attempt to perform the fraudulent transfer. As was noted earlier, this is far from being new stuff, but it is interesting to see that this particular malware, author coming from the Maghreb, wrote some of these features from scratch.

MSIL/PSW.Stealock.A

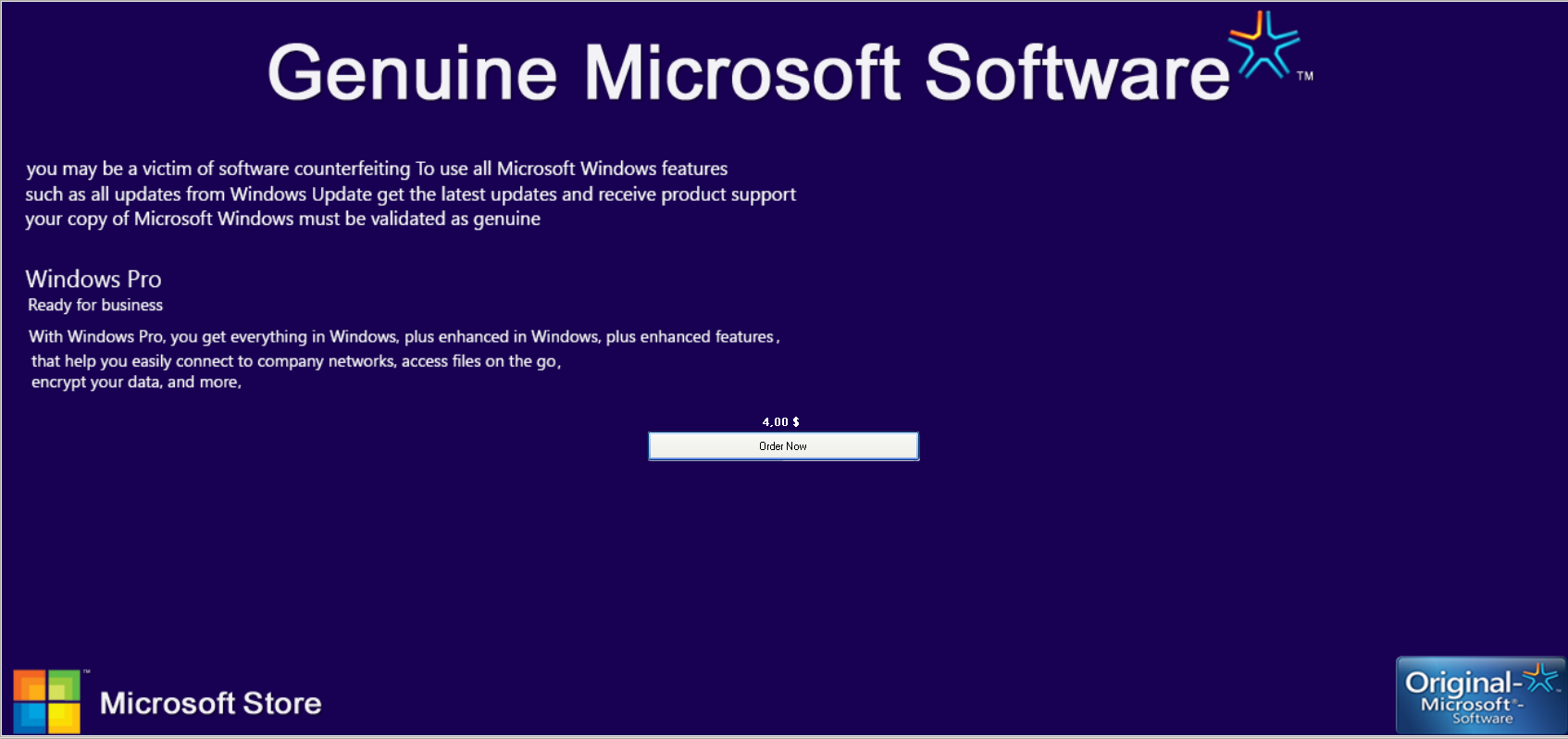

The second particularly interesting sample is a screen locker. The following screenshot is what is displayed to the user once the binary is executed. It is then impossible to dismiss this screen or to access any other program on the computer.

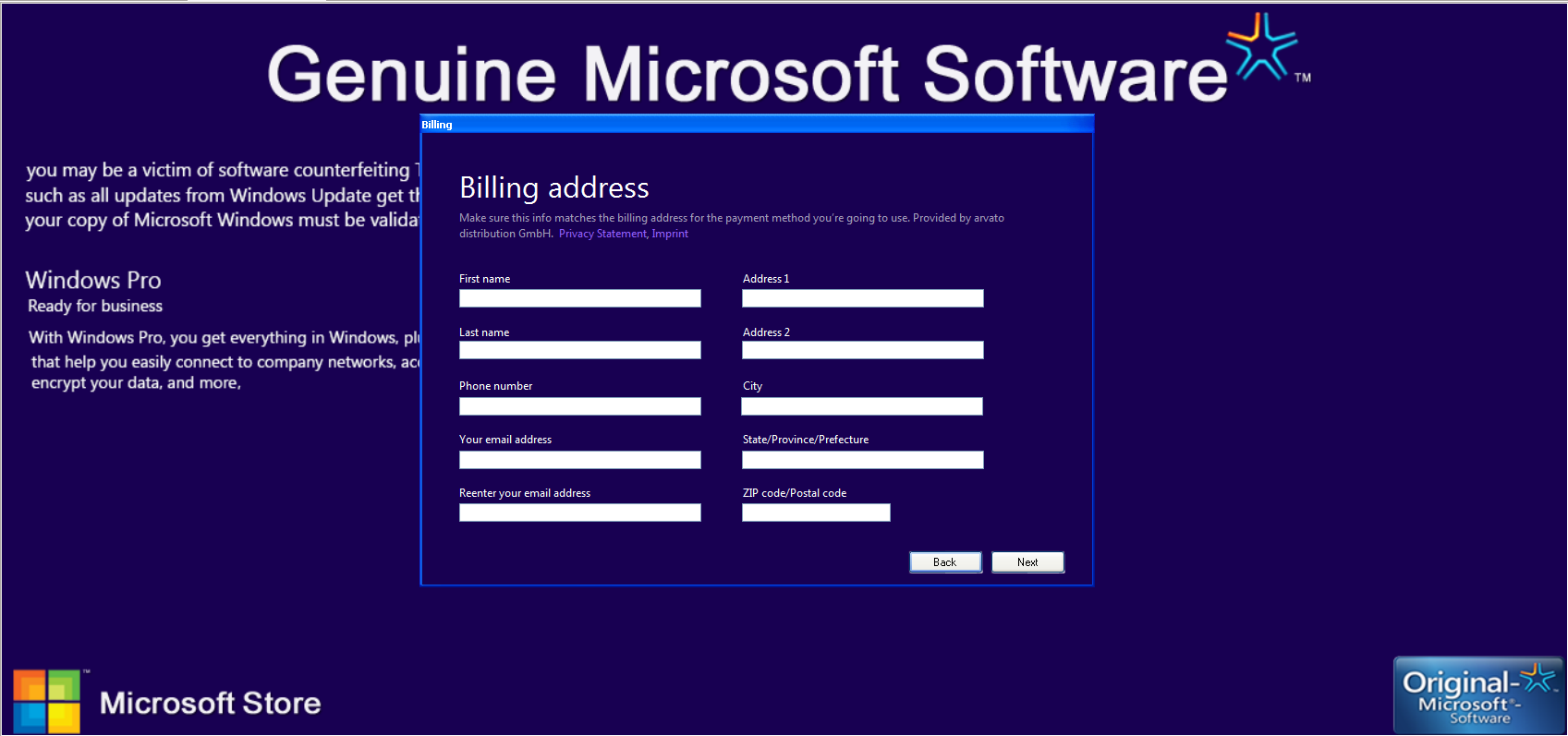

Was the author inspired by some of the more prevalent ransomware families like Reveton? The price is certainly not steep at $4. Of course, if a user enters credentials, their credit card information is sent to the malware author.

If the user proceeds and enter his information, he will be sent to another website, regcon.com, trying to automatically buy a downloadable software for $49.99. This software is of course another malware signed by the same certificate. Regular readers of We Live Security will know that such a ransom should never be paid. Like many ransomware variants, this one can be cleaned easily by rebooting Windows in safe mode and removing the registry key values that the malware sets for persistence, that is, to regain control of the machine after each reboot).

Conclusion

Malware signed by a fraudulent certificate, like the one we are describing here, are increasingly common these days. In order to obtain a code signing certificate, the applicant must go through a validation process.

Malware signed by a fraudulent certificate, like the one we are describing here, are increasingly common these days. In order to obtain a code signing certificate, the applicant must go through a validation process.

The Certificate Authority (CA) issuing the code certificate is responsible to run these checks in order to verify the applicant's identity. The details of this vary from CA to CA, but usually entail verifying information provided by the applicant through publicly available information. In this particular case, it appears that a company that no longer existed was used to obtain the certificate.

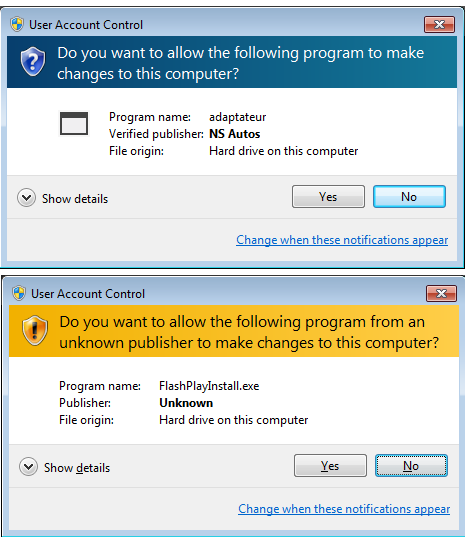

Although a code signing certificate is only meant to make sure that a particular piece of software is coming from the right source and has not been tampered with during transfer, it can give a false sense of security to the user. Also, running a digitally signed binary displays less warnings to the user before he can actually run it. Consider these two screenshots of the User Account Control dialog in Windows shown to the user when they execute the installer for the MSIL/Labapost.A threat. The first screenshot is what the user sees when the executable is signed with a trusted certificate while the second one shows what appears after the certificate was revoked.

ESET notified DigiCert that it issued a fraudulent certificate and they were very responsive: the certificate was revoked in a matter of hours.

SHA1 Hashes

MSIL/Spy.Labapost.A: 341af6a41078035845cd22ee35057c8a03c86bb4

MSIL/PSW.Stealock.A: f26e2b09e3c135dd87602013b13867b7616a0c8f

[1] Goutal, Sébastien, “Francophile Phishers”, Virus Bulletin Magazine, April 2012