[2nd update: added another batch of links for additional background.]

We were getting used to seeing some positives in the whole Autorun exploiting malware thing: while Microsoft remains equivocal about rolling out the patch that mitigates it to XP and Vista users, at least there's a fair amount of information around about how you can disable it.

The malware we detect as Win32/Stuxnet, unfortunately, is a worm (and rootkit) of a slightly different colour. It can propagate making use of a 0-day vulnerability described here and also listed by CVE as CVE-2010-2568, though there's no real information at CVE right now - the Knowledgebase link in the Microsoft Advisory doesn't go anywhere at the time of writing, either, so I guess these are placeholders.

No Click Necessary

The biggest problem is that Windows (specifically, the Windows Shell) can be tricked into executing malicious code presented in a specially-crafted shortcut (.LNK) file linking, in turn, to a malicious DLL (Dynamic Link Library). (We detect such shortcuts as LNK/Autostart.A.)

Microsoft's advisory states that the malcode is executed when the icon is clicked, but this is misleading: because the problem is in the way that Windows Shell fails to parse the shortcut correctly when it loads the icon, it isn't necessary to click the icon for the malicious code to be executed.

The advisory also suggests that for systems where Autoplay is disabled, the victim must manually browse to the root directory of the infected device (normally, using Windows Explorer). While this is true as far as it goes, research indicates that this is not much of a mitigation. The code will still be executed without any action on the part of the user once that folder is opened to access whatever legitimate files are on the device.

It’s Not A Bug, It’s …..

This malware has a number of interesting features.

- Two of the drivers being dropped were digitally signed by Realtek Semiconductor, a legitimate company, which should cause some consternation among those who think that code signing is a complete replacement for anti-malware products. (The certificate has since been revoked by Verisign.)

- The attack code has been extensively used around the globe to penetrate SCADA (Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition) systems used for running major industrial process, infrastructural processes such as power generation, and other facility processes.

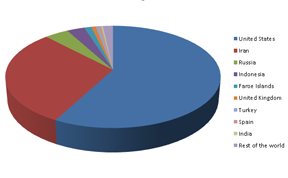

- Threat volumes, according to our own ThreatSense.Net® early warning system are already high enough to indicate that infections have already spread well beyond the walls of industrial plants and power stations, and research has yielded some interesting distribution patterns. However, there's further discussion on that at the end of this post. The following chart shows the relative distribution of reports by locale.

There's a little more discussion on what those figures might really mean at the end of this article.

Thanks for Sharing

Note also that USB devices are not the only potential vector: network shares and webDAV shares can also be used to distribute malicious .LNKs. Affected platforms (essentially all current Windows versions) are listed in the advisory: it's likely that there won't be a patch for XP SP2 or Windows 2000, which have reached the end of their support life.

And Now for the Good News

Microsoft suggest three mitigations:

* disabling Autorun (always a good idea, but not much help in this instance)

* restricting user rights (adherence to the principle of least privilege, i.e. not giving users more privileges than they need, is something we're quite keen on here, too)

* blocking SMB connections on the perimeter firewall to reduce the risk from file shares

Microsoft also suggests two workarounds, and describes how to effect them:

* disable the display of shortcuts

* disable the WebClient service

Unfortunately, both these options will have significant impact on some Windows users, since the first involves modifying the Registry (eek!) and the second will impact on SharePoint users.

Chester Wisniewski suggests deploying a GPO (Group Policy Object) to prevent users from executing programs except from drive C: this won't suit everyone, but certainly offers a viable alternative, especially in corporate environments.

So What Do Those Figures Really Mean?

Here's the detail from that earlier pie chart:

| United States | 57.71% |

| Iran | 30.00% |

| Russia | 4.09% |

| Indonesia | 3.04% |

| Faroe Islands | 1.22% |

| United Kingdom | 0.77% |

| Turkey | 0.49% |

| Spain | 0.44% |

| India | 0.29% |

| Rest of the world | 1.73% |

However, while figures from Microsoft indicate somewhat similar rankings (a post here suggests that the US, Indonesia. India and Iran are the most reported locales), the post also shows figures factoring in MMPC-monitored machines, it shows the volumes of reports from Iran and Indonesia as being dramatically higher than the global average, while even the figures for the next-ranked countries - in descending order India, Ecuador, US, Pakistan/Lebanon (tied) and Taiwan - are far closer to the global average.

If the disparity in these statistics tells us anything at all - apart from how difficult it is to extrapolate meaningfully from quite large, self-selecting populations of protected machines to the entire Internet - it's that there's something quite complex and dynamic happening here. While this incident may have started with targeted attacks on SCADA sites, these seem to be disappearing into the background noise as the number of attempted attacks escalates.

There are aspects of the code suggesting that the original attacks originated with a "normal" software developer rather than with the criminal gangs responsible for most malcode, or even the government- or military-funded hacker groups we often associate with targeted attacks. It may be that what we're seeing is a conventional software developer at the beginning of a learning curve.

The security industry has always avoided self-replicating code even for "good" projects and criminal malware developers have also moved away from self-replicating malware towards Trojans spread by a variety of other channels. And one of the most compelling reasons for that is that once self-replicating code is released, it's difficult to exercise complete control over where it goes and what it does. For the bad guys, it has the additional disadvantage that as it becomes more prevalent and therefore more visible, its usefulness as a malicious resource is depleted by public awareness and the availability of protection.

But that doesn't mean that this particular attack is going to vanish any time soon, AV detection notwithstanding. Now that particular vulnerability is known, it's certainly going to be exploited by other parties, at least until Microsoft produce an effective fix for it, and it will affect some end users long after that.

Acknowledgements

The real heavy lifting on this research was done by Juraj Malcho and his colleagues in Bratislava, and by Aleksander Matrosov in Russia, though for this article I've also drawn (of course) on research from others in the security community, including researchers from Internet Storm Center, Sophos, Kaspersky , F-Secure and Microsoft. No researcher is an island....

Other Links

- http://news.softpedia.com/news/Microsoft-Confirms-Zero-Day-Crticial-Vulnerability-147964.shtml

- http://www.informationweek.com/news/security/attacks/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=225900068&cid=alert_art_sec_d_f

- http://isc.sans.edu/diary.html?storyid=9181

- http://www.theregister.co.uk/2010/07/16/windows_shortcut_trojan/

- http://krebsonsecurity.com/2010/07/experts-warn-of-new-windows-shortcut-flaw/

- http://www.kb.cert.org/vuls/id/940193

- http://youtu.be/1UxN7WJFTVg

- http://www.h-online.com/security/news/item/Trojan-spreads-via-new-Windows-hole-1038992.html

- http://eddywillems.blogspot.com/2010/07/microsoft-lnk-usb-worm-rootkit-issue.html

- http://www.h-online.com/security/news/item/Microsoft-confirms-USB-trojan-hole-1040028.html

- http://go.theregister.com/i/cfh/http://www.theregister.co.uk/2010/07/19/win_shortcut_vuln/

- http://blogs.technet.com/b/msrc/archive/2010/07/16/security-advisory-2286198-released.aspx

David Harley CITP FBCS CISSP

ESET Senior Research Fellow