Imagine you are the person in charge of operations for a property company that manages a dozen buildings in a number of cities. What would you do if you got the following text on your phone?

“We have hacked all the control systems in your building at 400 Main Street and will close it down for three days if you not pay $50,000 in Bitcoin within 24 hours.”

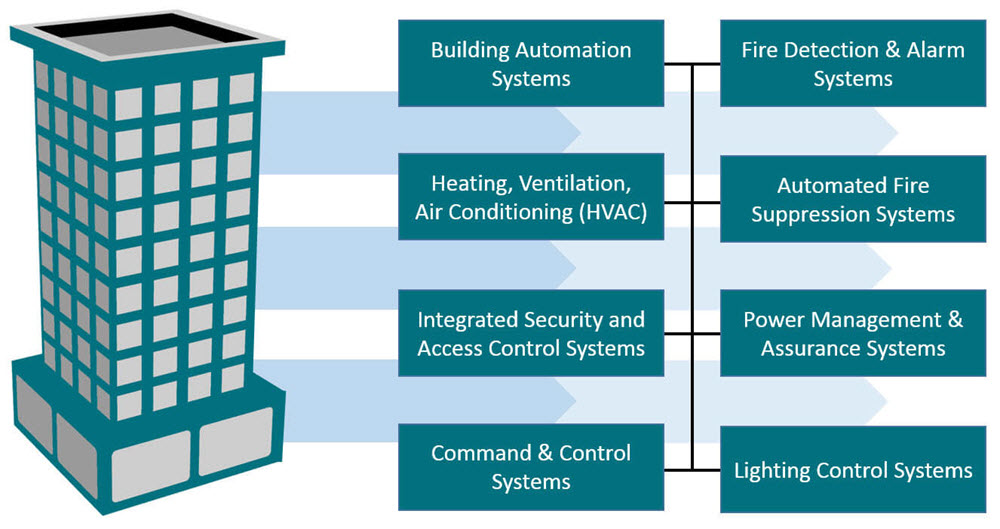

In this scenario, the building at that address is one of several upscale medical clinics in your company’s portfolio. The buildings all use something called a BAS or Building Automation System to remotely manage Heating, Air Conditioning, and Ventilation (HVAC), as well as fire alarms and controls, lighting, and security systems, and so on. As many as eight different systems may be remotely accessible.

Figure 1 – Building Automation System, or BAS

In this scenario, if someone has in fact gained control of the BAS, then it is entirely possible that the sender of the threatening message could make good on their threat. This is not an imaginary scenario. I have met with someone who got a message like that and it was not a hoax. When her company bravely refused to pay the attackers, use of the targeted building was indeed disrupted.

Siegeware is real

I would not be writing about this form of cybercrime if I thought there was only one isolated incident. No security researcher wants to spread unwarranted fear, or give criminals any ideas. But it turns out that the law enforcement officers who were contacted for assistance by the operations manager in this case told her: “We’ve seen this before.” In other words, this was not the first time that criminals have tried this type of attack and in my opinion it is better to let potential victims know about threats so that they can plan how to defend against them, rather than hope those threats don’t materialize.

Clearly, holding a building for ransom by leveraging its reliance upon software is now on the criminal agenda, part of the expanding arsenal of techniques for profiting from the abuse of technology. In my experience, giving a name to different types of attack helps spread awareness of them and focus efforts to defend against them. So, instead of saying holding a building for ransom by leveraging its reliance upon software, I suggest we call it siegeware.

From Neolithic hilltop settlements to medieval castles and walled cities, human structures have always been a target for nefarious activity, often besieged by aggressors because access to them is essential to their functionality, be that living, working, meeting, trading, storage, or medical care. Today, the functionality of many buildings – such as the ability to control room temperature, door locks, and alarms – is controlled by a Building Automation System (BAS).

Numerous practical and financial benefits can accrue from enabling remote access to a BAS, but when you combine criminal intent with poorly protected remote access to software that runs a building automation system, siegeware is a very real possibility. To put it another way, siegeware is the code-enabled ability to make a credible extortion demand based on digitally impaired building functionality.

Siegeware outlook and response

There was some good news in the example that was shared with me. The company already had an effective crisis response plan and although this was a new scenario for them, the response team was able to quickly put backup measures in place. This enabled the company to refuse to pay the ransom demand. However, the criminals did disrupt normal use of the building by tenants.

How widespread will the siegeware problem become in 2019? That will depend on several factors: how aggressively cases are investigated by law enforcement; how many victims refuse to pay; and how many targets of opportunity the bad actors can find.

To this last question, you can use Shodan – the internet search tool – to get a sense of scale. When I searched in mid-February 2019 for BAS systems that were reachable from the public internet I found 35,000 potential targets globally. That was for just one category of product, and the number was up from about 21,000 at the end of August, 2018.

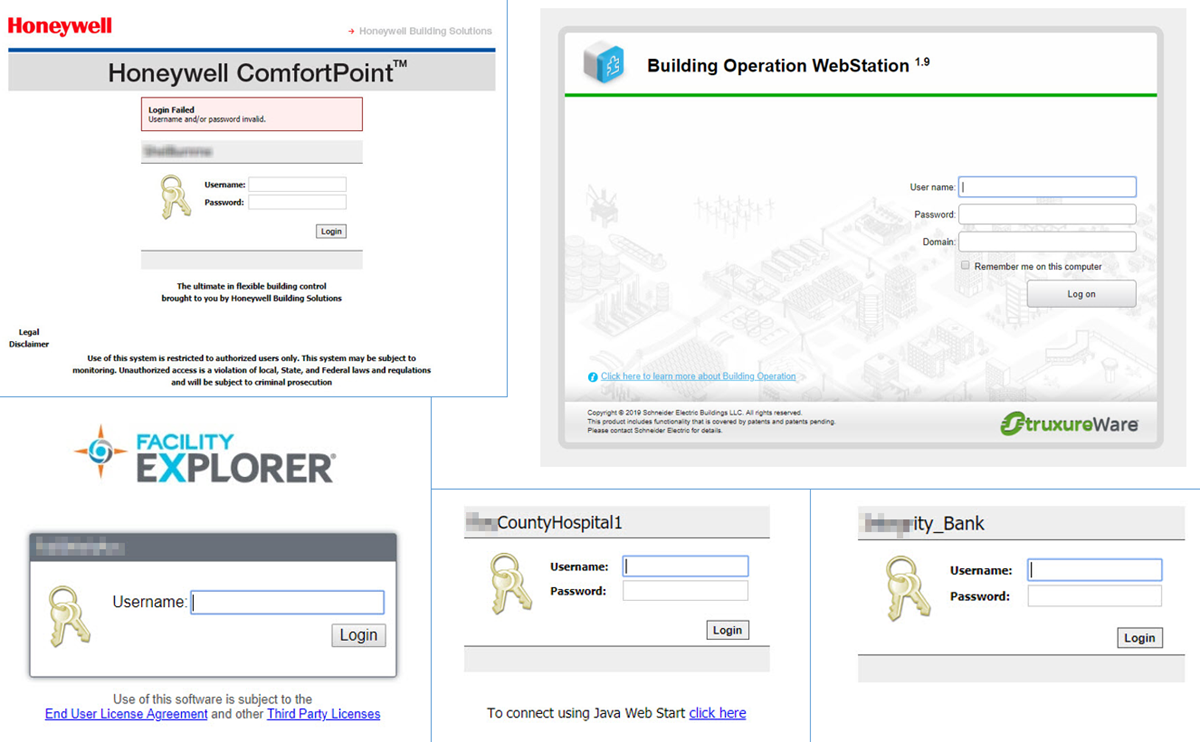

Right now, a criminal searching for a range of different BAS systems to target probably has close to 30,000 to choose from in the US alone. These are IP addresses which, when entered into a web browser, may produce BAS login screens like the examples below (I have obscured building names/locations):

Figure 2 - Examples of BAS login screen

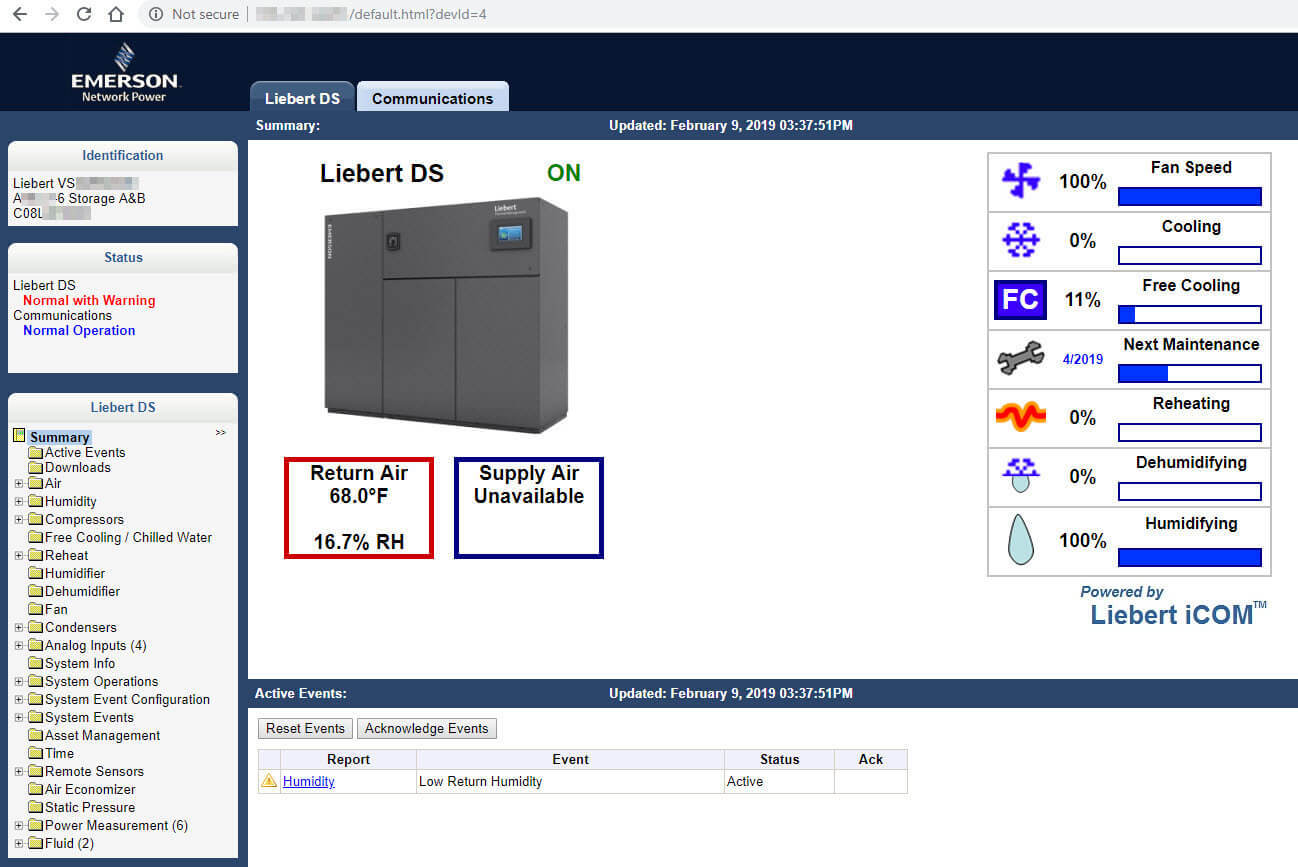

The next stage for the attacker is to try the default user name and password for that type of system (these can be found with basic Google skills). Unless the defaults have been changed, and rate limiting on password attempts has been implemented, a motivated criminal will probably gain access. The immediate goal of this search-and-guess-password process is something that looks like this – a cooling system dashboard:

Figure 3 - A cooling system dashboard

Sometimes you don't even need to guess a password to get this far: this is a live dashboard, accessible to anyone on the internet, without a password. And because the internet is so good at documenting technology, you can easily determine that this is a Liebert DS data center cooling system, for which a lot of documentation is available online. It is also relatively easy to figure out who owns the system (a large university that I am not going to name), and where it is located (on the East Coast of the US).

Although most organizations are not as egregiously unprotected as this, even a cursory search reveals that in the US there are scores of clinics and hospitals exposing their BAS logins to abuse, not to mention hundreds of schools and universities, as well as quite a few banks. You don’t have to be a particularly imaginative criminal to see some real possibilities there.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be like this. There is plenty of advice out there for organizations that want to reduce the risk of siegeware attacks. A good place to start would be “Intelligent Building Management Systems: Guidance for Protecting Organizations” available on the Security Industry Association website along with a number of other useful resources. I found this US DoD document very informative as well: Unified Facility Criteria, UFC 4-010-06 Cybersecurity Of Facility-Related Control Systems.

That DoD document on “Unified Facility Criteria” is dated 2016, which tells you that the cybersecurity of building technologies is not a brand new challenge. In fact there were several early warning signs that presaged the emergence of siegeware. Phil Zito, founder and CEO of “Building Automation Monthly” published How to Hack a Building Automation System in July of 2013. There was the Black Hat Asia presentation “Owning a building” by Billy Rios in early 2014. In early 2016 the reality of smart building hacking was documented in this CSO article titled “IBM's X-Force team hacks into smart building.”

So where do things go from here? Clearly, now is a good time to determine the state of facility automation in the building where you work. Is there any level of automation, and if so, how is access to the building automation system protected?

A key factor to be aware of when making enquiries along these lines is the relationship between building owners, property managers, and contractors. My research suggests that some contractors find it very convenient to install a web-based login that they can then access at any time, remotely, and with ease, often over smartphones and tablets. It is possible that the managers/owners of the building will not know about such remote access unless they ask.

So, if you are at all concerned about the possibility of a siegeware attack, ask around to see if there is any remote access for the BAS in “your” building. Then try to find out how well protected it is. Has access been placed behind a firewall? Does access require a VPN connection? Is access protected with multi-factor authentication or just a password? If the latter, then immediately call a meeting to get that fixed, and I don’t just mean make sure it is a hard-to-guess password. At a bare minimum there has to be rate limiting and lockout on failed password attempts and “alarms” that go off in multiple places when such incidents occur.

Frankly, anything less than hiding the BAS login behind a VPN with 2FA means a building is at risk from criminals wielding siegeware. With 2FA now being so widely available and easy to use, failure to take advantage of it to protect a BAS is likely to fail a reasonable test, should building tenants sue in the wake of a siegeware attack.

The future of IoT as attack vector

Of course, offices and factories are not the only buildings being automated. Many homeowners are embracing the Internet of Things (IoT) and the home automation that these devices enable. My colleague Tony Anscombe has been researching the threats that may come with a “smart home” and will be presenting on this at Mobile World Congress (MWC) – taking place February 25 – 28, 2018 in Barcelona.

In the 2017 edition of the ESET Trends report I wrote about several ways in which criminals might try to monetize hacks of IoT devices including jackware for cars (see RoT: Ransomware of Things). The key word here is "monetize" because potential abuses of technology are typically not criminalized until criminals devise a clear path to easy money from such abuse. In the case of siegeware, and also jackware, a lot of people have their fingers crossed that this path is discovered later rather than sooner.

Resources

In the US, the Real Estate ISAC or Information Sharing and Analysis Center, offers a number of security resources for the commercial real estate industry. Firms that join the organization get regular updates on a wide range of threats. The Real Estate ISAC is one of a number of such centers created to help critical infrastructure owners and operators protect their facilities, personnel and customers from cyber and physical security threats and other hazards; ISACs collect, analyze and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resiliency.

Here are some more resource links:

- An article on the facilities management and building operations management (BAM) website facilitiesnet has this article: "Can Hackers Target Your Building Automation System?"

- Excellent 2018 article from kW Engineering on Protecting Your Building: Cybersecurity in Building Automation by Lyn Gomes.

- Very helpful “Intelligent Building Management Systems: Guidance for Protecting Organizations” available on the Security Industry Association website.

- An informative DoD document: Unified Facility Criteria, UFC 4-010-06 Cybersecurity Of Facility-Related Control Systems.

- The article How to Hack a Building Automation System.

- The Black Hat Asia presentation “Owning a building” by Billy Rios (the video is here).

- The CSO article titled “IBM's X-Force team hacks into smart building”

- 2018 FBI Private Industry Notification: Anticipatory Awareness Message: Cyber Security for Smart Buildings.

- The Real Estate ISAC or Information Sharing and Analysis Center offers numerous resources to members.

- Check out the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International website section on cybersecurity.

- And be sure to establish connections with your local Infragard chapter (there are 82 of them around the US).