ESET researchers have investigated a distinctive backdoor used by the notorious Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group known as Turla (or Snake, or Uroburos) to siphon off sensitive communications from the authorities of at least three European countries. The group has been deploying the tool for years now – and we’ve found that the list of high-profile victims is longer than previously thought.

Whitepaper download

The victims include Germany’s Federal Foreign Office, where Turla implanted the backdoor on several computers and used it for data theft for almost the whole of 2017. In fact, Turla’s operators first compromised the network of the country’s Federal College of Public Administration, using it as a stepping stone to breaching the network of the Foreign Office in March 2017. It wasn’t until the end of the year that Germany’s security service detected the breach, which itself was only made public in March 2018.

Importantly, our own investigation has determined that, beyond this much-publicized security breach, the group has leveraged the same backdoor to open a covert access channel to the foreign offices of another two European countries, as well as to the network of a major defense contractor. These organizations are the latest known additions to the list of victims of this APT group that has been targeting governments, state officials, diplomats, and military authorities since at least 2008.

Dissecting the backdoor

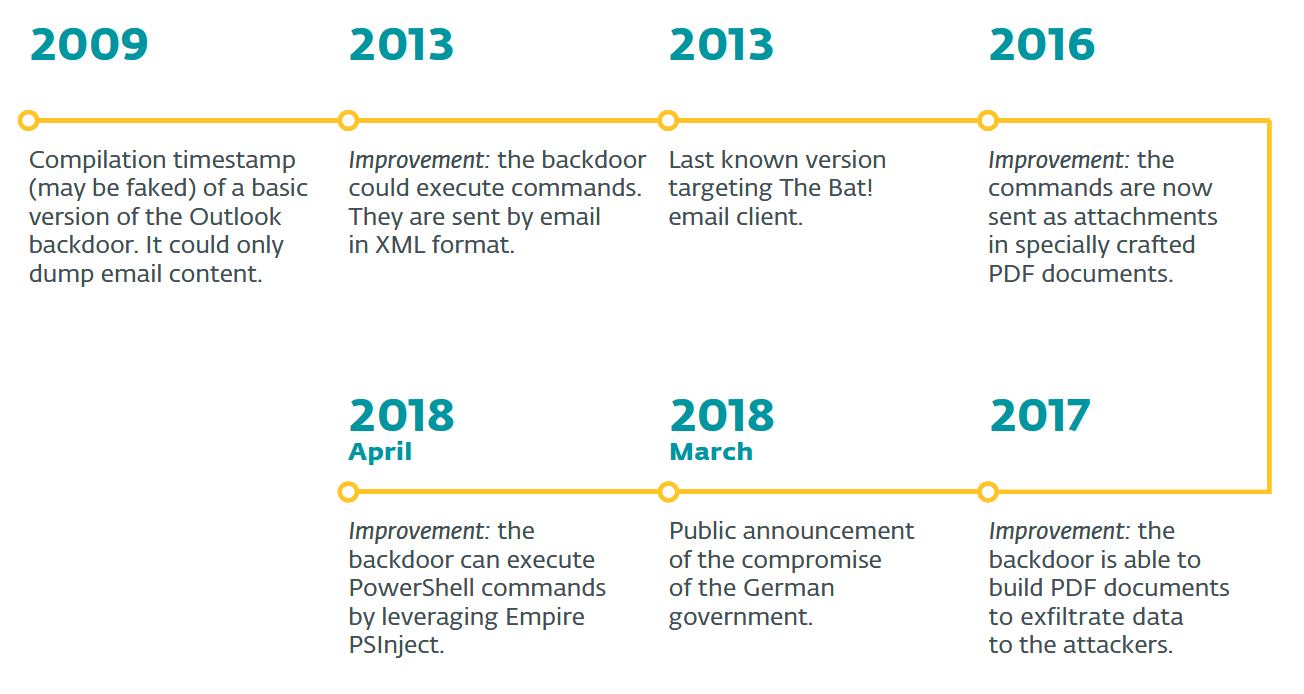

The backdoor that is the subject of our analysis has come a long way since it was created, possibly as far back as 2009. Over the years, its authors have been adding various functionalities to the tool, ultimately endowing it with a rare degree of stealth and resilience. The most recently discovered version, from April 2018, incorporates the ability to execute malicious PowerShell scripts directly in computer memory, which is a tactic that threat actors of various stripes have been embracing in the past few years.

Figure 1 – Turla Outlook backdoor timeline

The backdoor’s more recent iterations target Microsoft Outlook, although its older versions also took aim at the The Bat! email client, which is used mostly in Eastern Europe. Importantly, Turla’s operators don’t exploit any vulnerabilities either in PDF readers or Microsoft Outlook as attack vectors. Unusually, the backdoor subverts Microsoft Outlook’s legitimate Messaging Application Programming Interface (MAPI) to access the targets’ mailboxes.

Rather than using a conventional command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure, such as one based on HTTP(S), the backdoor is operated via email messages; more specifically, through specially crafted PDF files in email attachments. The compromised machine can be instructed to carry out a range of commands. Most importantly, these include data exfiltration, as well as the downloading of additional files and the execution of additional programs and commands. Data exfiltration itself also takes place via PDF files.

The backdoor – which comes in the form of a Dynamic Link Library (DLL) module and can be placed anywhere on the hard drive – is installed using a legitimate Windows utility (RegSvr32.exe). Meanwhile, persistence is accomplished by tampering with the Windows registry, which is frequently the case when Windows systems are compromised. In this case, Turla sticks to a tried-and-tested technique known as “COM object hijacking”. This ensures that every time Microsoft Outlook is launched, the backdoor is activated.

Doing the bidding

Whenever the victim receives or sends an email message, the malware generates a log that contains metadata about the message, including about its sender, recipient, subject, and its attachment name. On a regular basis, the logs are bundled together with other data and transmitted to Turla’s operators via a specially-crafted PDF document that is attached to an email message.

Additionally, in each incoming email, the backdoor checks for the presence of a PDF that may contain commands from the attacker. In fact, it is “operator-agnostic”, meaning that it accepts commands from anybody who can encode them into a PDF document. As a corollary, Turla’s operators are able to regain control of the backdoor by sending a command from any email address, should any of their hardcoded – but updatable – email addresses be blocked. The backdoor’s level of resilience to takedowns is almost on a par with that of a rootkit that, in inspecting inbound network traffic, listens for commands from its operators.

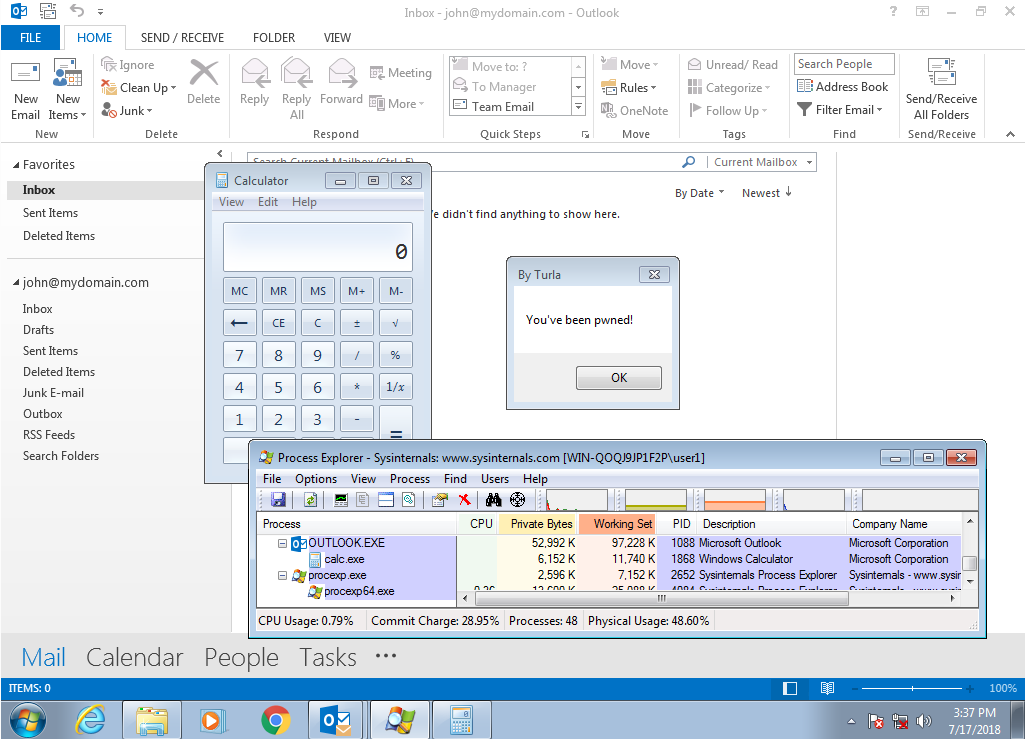

Even though ESET researchers haven’t obtained any sample of a PDF containing actual commands for the backdoor, the knowledge of its inner workings has enabled them to generate a PDF document (see Figure 2) with orders that the backdoor can interpret and execute.

Figure 2 – Execution of the commands specified in the PDF document

The malware generally goes to great lengths to embed itself out of sight on compromised machines. For example, while it is possible, for a few seconds, to catch a glimpse of an incoming email message in the unread email count indicator, no email received by the attacker ever shows up in the mailbox. Similarly, the malware also blocks any notifications of incoming email messages sent by its operators.

In conclusion

This is far from the first time that ESET researchers have documented the resourcefulness of Turla’s operators in reaching their goals while staying under the radar. Much as our recent analyses of the group’s backdoor Gazer and its campaign targeting Eastern European diplomats have shown, the group continues to employ advanced techniques in a bid to spy on its targets and to maintain persistent malware on compromised machines.

The Turla backdoor is a fully-fledged backdoor that uses customized and proprietary techniques, can work independently of any other Turla component, and is fully controlled by email. In fact, ESET researchers are not aware of any other espionage group currently utilizing a backdoor that is entirely controlled by emails, and specifically through PDF attachments.

A full and comprehensive list of Indicators Of Compromise (IoCs) and samples can be found on GitHub.

For a detailed analysis of the backdoor, head over to our white paper Turla Outlook Backdoor: Analysis of an unusual Turla backdoor.