Flash back on Operation Windigo

In March 2014, we released a paper about what we call Operation Windigo, a set of Linux server-side malware tools used to redirect web traffic, send spam and host other malicious content. This was the result of nearly a year's worth of research effort that consisted of the in-depth analysis of different components, observation of how they were used and linking it all together. We are very proud that our work was recognized by the industry at VB2014 where our paper was awarded the inaugural Péter Szőr Award for best technical research.

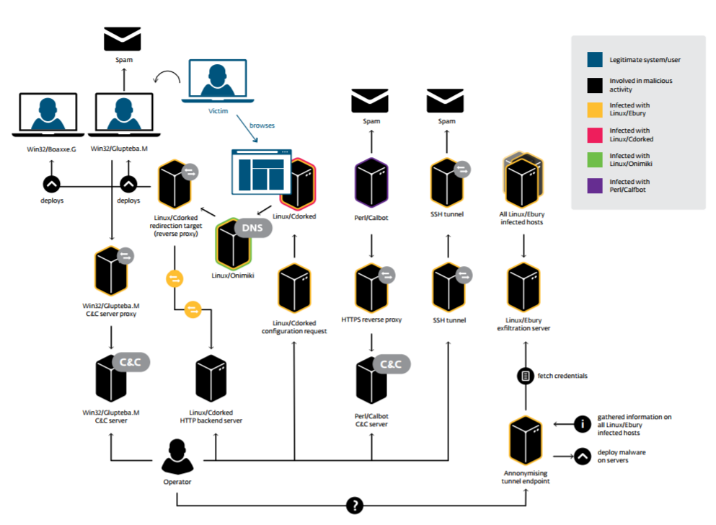

At the core of Operation Windigo is Linux/Ebury, an OpenSSH backdoor and credential stealer that was installed on tens of thousands of servers. Using that backdoor, the attackers installed additional malware to perform web traffic redirection (using Linux/Cdorked), send spam (using Perl/Calfbot or SSH tunnels) and, most importantly, steal credentials when the OpenSSH client was used to spread further.

Since the release of that paper we wrote multiple updates regarding Windigo and Ebury. Today we have two new articles: this one about the arrest and sentencing of Maxim Senakh and a technical update on the new Ebury variants out there.

How ESET collaborates with law enforcement

As malware researchers at ESET, one of our roles is to document new threats and protect our customers from them. The scope we are given is actually larger: if at all possible, our job is also to protect all Internet users. This can take the form of takedowns, disruptions or even helping to get cybercriminals arrested. These operations cannot be accomplished without working with others and usually requires the involvement of various law enforcement agencies.

While malware researchers are capable of dissecting malware, analyzing their behavior, noting code similarity between samples and finding artifacts left in malware files such as compilation timestamps; the attribution of a cyberattack to a given individual or group is the job of law enforcement. Unlike private companies, law enforcement agents can legally seize C&C servers, follow the trails from monetary transactions and work with ISPs to identify the people profiting from crime.

In the case of Windigo, we collaborated with the FBI by sharing technical details about the malicious operation and the malware components involved, allowing the FBI investigators to better understand the various parts of this very complex scheme. They also used our report to explain exactly what Windigo is to prosecutors, lawyers and judges.

The story of Maxim Senakh

It wasn’t without difficulty that the FBI apprehended one of the conspirators behind Operation Windigo. One of the ways the Ebury botnet was monetized was by displaying unwanted advertisements to unsuspecting users visiting compromised web servers. According to the indictment, the FBI followed the money trail of revenues generated from advertising networks. The ads were visited with traffic generated by the Ebury botnet. This resulted in the identification of a Russian citizen using multiple fake identities to register domain names used for malicious purposes and to manage monetary transactions related to the unwanted advertising operation.

Maxim Senakh was subsequently arrested on August 8th 2015 by Finnish authorities at the Finland-Russia border at the request of US federal authorities. It was not a smooth process: Russia objected to the arrest and extradition process on the basis that information related to Senakh’s illegal activity was not sent to Russia first. Soon after, the USA submitted an extradition request to the Finnish Ministry of Justice, who agreed to the request after a complex evaluation process. This decision could not be appealed, and Senakh was extradited to the US in February 2016, awaiting his trial.

Senakh originally pleaded not guilty. This meant both sides were preparing for a jury trial. ESET was asked to provide expert witnesses to testify at the trial and explain what Windigo and Ebury are, how the findings, numbers and facts present in our report were collected and why they are accurate. Writing technical reports on malware is one thing; testifying in a court of law in front of the alleged criminal is quite another. Despite the pressure, we accepted, knowing our involvement would be only related to the technical aspects of the operation. Proof of attribution was left to the FBI.

In March 2017, Senakh announced to the court that he would be changing his plea to guilty to a reduced set of charges. A trial was no longer necessary.

In August, he was sentenced to 46 months in prison in the state of Minnesota.

Here’s a summary of the timeline:

- 2015-01-13: Indictment against Maxim Senakh is produced, charging him with 11 counts.

- 2015-08-08: Senakh is arrested by Finnish authorities at its border while returning to Russia after personal travel.

- 2016-01-05: Finland agrees to the extradition of Senakh.

- 2016-02-04: Senakh is extradited from Finland to the US, where he pleads not guilty to all charges against him.

- 2017-03-28: Senakh enters into a plea agreement with the US Attorney's Office and pleads guilty to the first count of the indictment, the remaining 10 being dismissed.

- 2017-08-03: Senakh is sentenced to 46 months in federal prison, without the possibility of parole.

The outcome – where is Windigo now?

Did the arrest of Senakh shut down the Operation Windigo botnet? From what we’ve seen, only partially.

Not long after Senakh’s arrest in 2015, our telemetry showed a sharp decrease in the traffic redirected by Cdorked, the component responsible for sending web visitors to exploit kits or unwanted advertisement pages. As we explained earlier, the FBI determined that this malicious activity benefited Senakh directly. This activity has not resumed.

We are not the only ones who think Cdorked could be extinct: two weeks after Senakh’s arrest, Brad Duncan, a security researcher from Rackspace, noticed a significant drop in Windigo activity related to the web traffic redirection.

This is good news. However, Windigo was not put to rest completely. We’ve seen new variants of Win32/Glupteba, a Windows malware family that has strong ties with Windigo; Glupteba acts as an open proxy.

Also, last but not least: the malware component at the core of Windigo, the Linux/Ebury backdoor, has evolved. Development has continued and important changes were made to the latest versions, such as evasion of most of the public indicators of compromise, improved precautions against botnet takeover and a new mechanism to hide the malicious files on the filesystem. Read our complete analysis of the updated Linux/Ebury for more details.