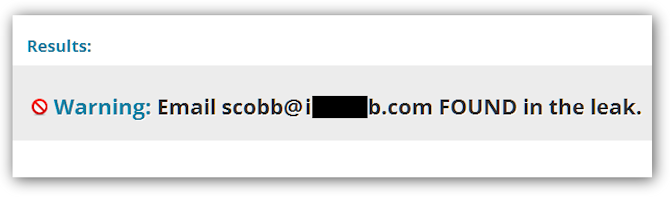

Changing the passwords on your online accounts might not sound like a fun weekend activity, but that's what I did last weekend. Why? Because on Sunday I found out that one of my email addresses was in the list of Yahoo! logins whose passwords were exposed by sloppy handling of a credential file (an incident on which David Harley commented in a recent blog post). Here's what I saw on Sunday, on a special web page created by the kind folks at Sucuri Labs:

Note that the "scobb at something dot com" email address was not a Yahoo! Mail address but one that I created and managed myself, associated with a domain that I owned for many years (somewhat obfuscated in the image). The fact that the "Yahoo! password breach" exposed non-Yahoo! email addresses and their corresponding passwords is an aspect of this particular breach which was not immediately apparent because the initial headlines for this story read "Hackers expose 453,000 credentials allegedly taken from Yahoo service." I'm not criticizing Dan Goodin's breaking story in arstechnica, it's just natural for media attention to remain be focused on the biggest name involved, even as the story develops.

So how did I find out that my address was among those exposed? Obviously I used the Sucuri Labs web page that queried the list of leaked addresses (the list was published on the Internet by the folks that stole it from the server at Yahoo which they penetrated with a SQI injection attack). But why did I even bother to look at that web page? Because back in 2006 or so I was considering posting some articles on a website called Associated Content and I created an account there. If you go to www.associatedcontent.com today you will see that it is now Yahoo! Voices. I just happened to notice the Associated Content connection in my security news feed.

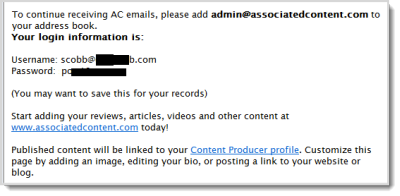

Just for kicks I searched my email archive and came up with this gem, the welcome message I received after signed up with Associated Content. This message suggests that Associated Content did not have the right approach to security back then (the original email displays the password in plain text).

Just for kicks I searched my email archive and came up with this gem, the welcome message I received after signed up with Associated Content. This message suggests that Associated Content did not have the right approach to security back then (the original email displays the password in plain text).

The fact that this attitude could persist through the acquisition by a much larger and, one would hope, more diligent company, is disconcerting to say the least. That's why I decided to do some serious password changing last weekend, just to be on the safe side. After all, millions of passwords have been exposed in the last 45 days, that we know off, including sites such as LinkedIn, Nvidia, and Phandroid. That makes now a good time to get the whole family to change up their digital credentials. The ESET blog has advice on how to go about improving your passwords, starting with a good collection of password-related articles here.

If you have some time left over after you have changed your passwords, you might want to email the CEOs of some of the companies that have let passwords leak out. Tell them to do a better job of protecting those who trust them to protect their information. Frankly, the standard of programming on too many big name websites fails to meet basic security standards. The technique used to get the password file from the Yahoo server, SQL injection, is widely known (consider this Search Security article on the subject from four years ago--plenty of time to put defenses in place, one would think).

Now would also be a good time for your company to review the way its websites are configured with respect to password handling, particularly if you have a support forum. The targets of the two latest credential exposing hacks to hit the news are forums. While two events do not make a trend, the news of these two events may attract copy-cat attacks. The very first thing you want to make sure of is that no passwords are being stored in clear text on web-facing servers. If you are a large company you might want to review all your sub-domains for old files that are lying around on servers from past acquisitions.