Today, we announce that a major law enforcement operation disrupted many botnets using a malware family that has been plaguing the internet for quite a long time: Gamarue, also known as Andromeda. This joint operation, involving law enforcement agencies world-wide, Microsoft, and ESET, has been ongoing for more than a year now.

Gamarue, mostly detected by ESET as Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos, has been around since at least September 2011 and was, for the most part, sold as a crimekit on underground forums. This crimekit proved very popular amongst cybercriminals and, that being the case, there are multiple, independent Wauchos botnets. In the past, Wauchos has been the most detected malware family amongst ESET users, so when approached by Microsoft to take part in a joint disruption effort against it, to better protect our users and the general public at large, it was a no-brainer to agree.

ESET provided technical analysis to this operation by closely tracking Wauchos botnets, identifying their C&C servers for takedown, and monitoring what its operators installed on victims’ systems. Through Microsoft, the information provided to law enforcement agencies as part of this operation included:

- 1,214 domains and IP addresses of the botnet’s command and control servers

- 464 distinct botnets

- 80 associated malware families

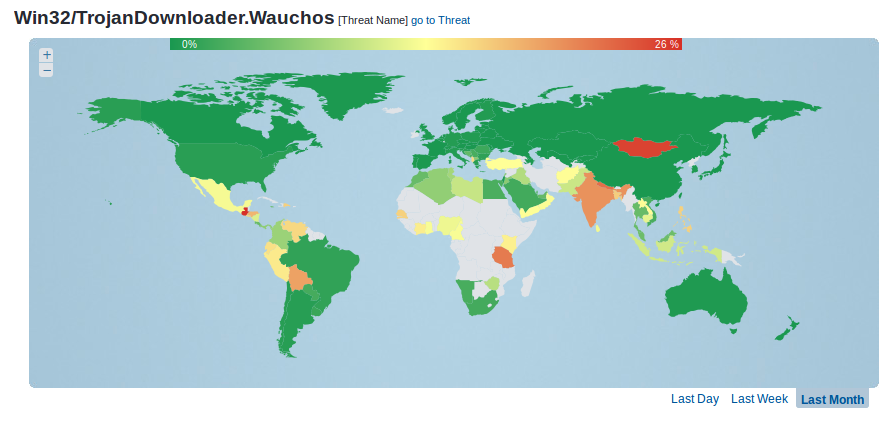

In Figure 1 you can see Wauchos’s prevalence map based on our telemetry data. Evidently, Wauchos is a global problem and any attempt to disrupt it is worth making. As you will notice throughout the article, the data shown are about a year old. This is when Wauchos’s activity was at its peak, according to our telemetry. As legal procedures do take some time, especially when arrests are involved, we chose these older data, as they are more representative of the period at which most of the research took place.

If you are worried that your Windows system might be compromised by this threat and are not an ESET customer, you can download and use the ESET Online Scanner, which will remove any threats, including Wauchos, it might find on your system.

What is Wauchos?

This very prevalent malware has been around for several years and has been covered in the past by multiple blog posts [1][2][3][4]. In this section, we will review the technical basics of this malware: what it is and how it is spread. The following section will cover technical details that we uncovered while tracking this malware family.

Wauchos is mostly used to steal credentials and download and install additional malware onto a system. Thus, if a system is compromised with Wauchos, it’s likely that there will be several other malware families lurking on the same system.

Wauchos is modular malware whose functionalities can easily be expanded by adding plugins. Plugins used include a keylogger, a formgrabber, a rootkit, a SOCKS proxy and a TeamViewer bot. There are five known major build versions of Wauchos, based on its own versioning scheme: 2.06, 2.07, 2.08, 2.09 and 2.10. For the first three versions, the build version was included in the first POST request sent to the C&C by the bot, so version identification was easy. Later versions of Wauchos removed the bv parameter in the POST request, but it is still relatively simple to identify the bot version by looking at the identification string sent to the server [3]:

Version |

Identification string |

|---|---|

| <= 2.06 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|bv:%lu|sv:%lu|pa:%lu|la:%lu|ar:%lu |

| 2.07 – 2.08 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|bv:%lu|os:%lu|la:%lu|rg:%lu |

| 2.09 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|os:%lu|la:%lu|rg:%lu |

| 2.10 * | {"id":%lu,"bid":%lu,"os":%lu,"la":%lu,"rg":%lu} |

(* Note the switch to JSON format.)

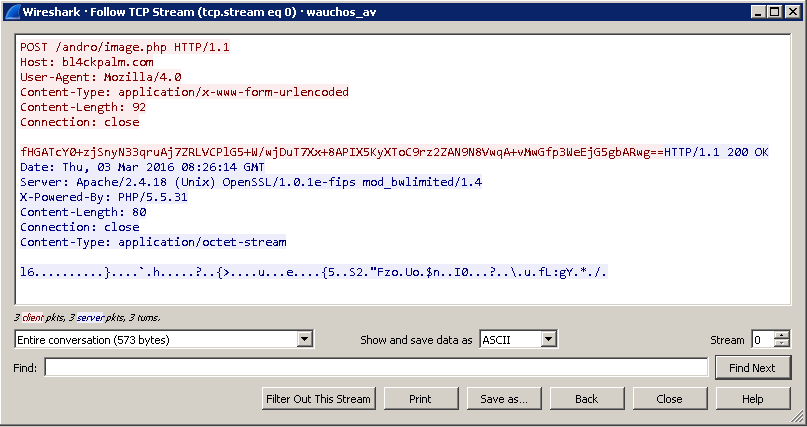

A typical POST request is shown in Figure 2. The identification string is RC4 encrypted and then encoded using base64.

Since a builder for version 2.06 was leaked a few years ago, we have seen quite a bit of that version of this botnet in our telemetry. However, according to our crawler data the latest version, 2.10, is the most prevalent.

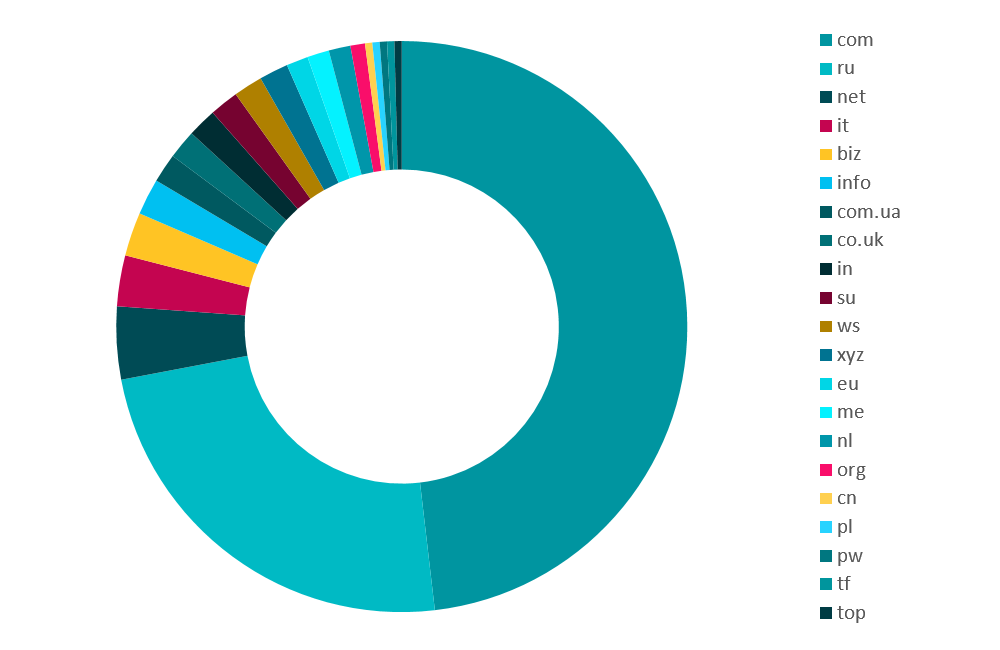

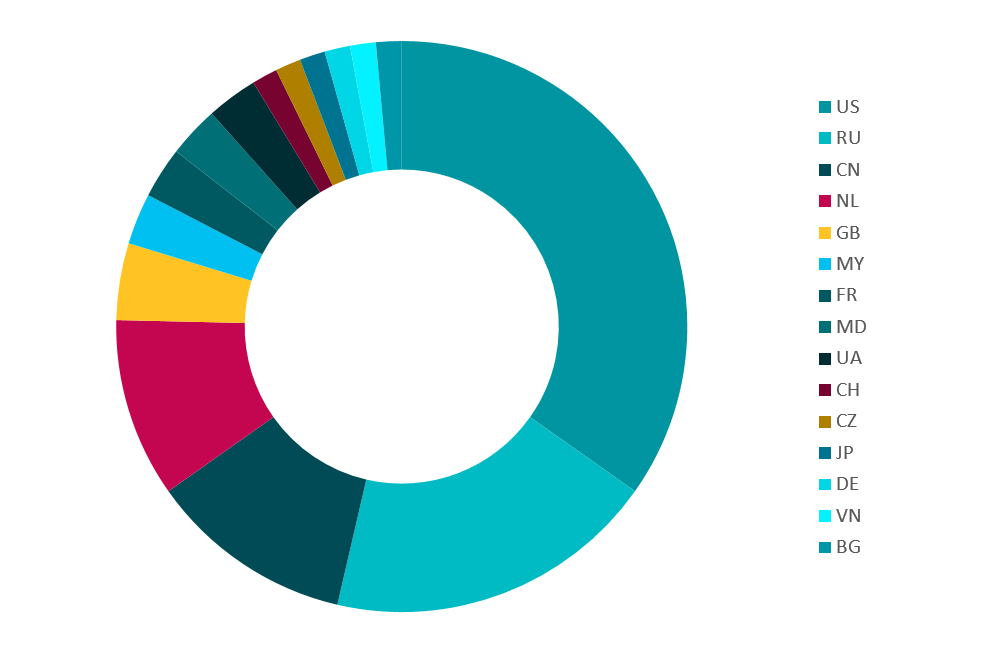

The truly global nature of this threat is also seen in the diversity of the command and control servers its operators use. Throughout our monitoring of this threat, we were able to discover dozens of Wauchos’s C&C servers every month. Figure 3 shows a snapshot of the different TLDs used by the C&Cs while Figure 4 shows the geographic distribution of these C&C server IPs when our crawler was connecting to them in November and December 2016.

Interestingly, a lot of samples we analyzed check the system’s keyboard layout and does not proceed with the infection if it matches one of the following:

- Russia

- Ukraine

- Belarus

- Kazakhstan

Infection vector

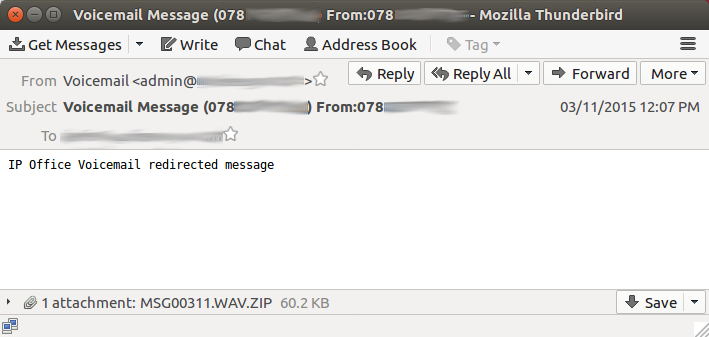

As Wauchos is bought and then distributed by a variety of cybercriminals, the infection vectors used to disseminate this threat vary greatly. Historically, Wauchos samples have been distributed through social media, instant messaging, removable media, spam, and exploit kits. Figure 5 shows a typical email spam with a Wauchos sample attached.

Pay-per-install malware

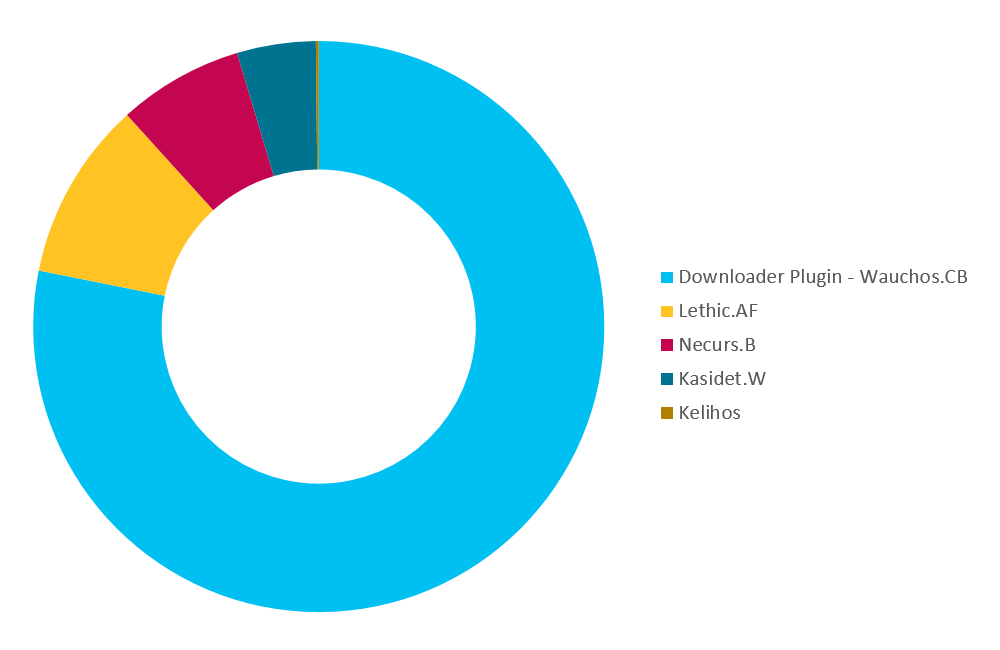

As described previously, Wauchos is mostly used to distribute other malware families. Through our automatic systems, we were able to derive statistics on what was downloaded by the Wauchos bots we were tracking. Figure 6 shows the different plugins that were downloaded by our crawler when first connecting to the C&C.

The first download is usually a plugin — more specifically, the downloader plugin we will discuss in a subsequent section. In terms of installed malware, most of the malware we saw distributed in December 2016 were spambots such as Win32/Kasidet, Win32/Kelihos or Win32/Lethic. Of course, as it is a pay-per-install scheme, these statistics tend to change from time to time. There was, as one might expect, other malware downloaded by Wauchos, but according to our telemetry data, the ones shown above are the most prevalent.

Technical analysis

In this section, we will present some technical details that have not been widely discussed in public and that provide context in light of the recent takedown. In particular, we will discuss two plugins that can provide side-channel communication to the botmaster, increasing the botnet's resiliency to a takedown operation.

Wauchos variants

First, to help our fellow researchers interested in this malware family, we will briefly describe the major variants, using ESET’s naming and to what they correspond.

Win32/Wauchos.B is the most prevalent detection for 2.06 Wauchos component while version 2.10 is mainly detected as Win32/Wauchos.AW. The other variants grouped under the Win32/Wauchos family are either plugins, packed versions of the aforementioned versions or other versions of the Wauchos malware, such as 2.07, 2.08 or 2.09; these are less prevalent according to our telemetry and thus less relevant to this discussion.

In the latest version of Wauchos (2.10), the bot supports the current commands:

Command ID |

Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Download and run a binary file |

| 2 | Download a plugin |

| 3 | Download malware update |

| 6 | Delete all plugins |

| 9 | Uninstall |

Plugins

Wauchos is an extensible bot that allows its owner to create and use custom plugins. However, there are some plugins that are widely available and that are used by many different botnets. In this section we will review the different plugins our tracking mechanism was able to download.

Title |

Detection name |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| SOCKS Proxy | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.O | Accepts connections and acts as a network proxy |

| TeamViewer | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.BA | Embeds TeamViewer application that will launch in hidden mode and allow criminals to connect back and control compromised system |

| Form Grabber | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.AZ | Steals content entered into web forms by the user |

When a bot downloads a plugin, it must first decrypt its header with the RC4 key. The header contains the unique key required to decrypt the payload. Once decrypted, the last operation is to decompress the plugin using aPLib. Once this is done, the malware uses a custom loader to load this binary blob into memory. As the binary blobs are already memory-page aligned they can be loaded directly into memory and executed.

The number of different RC4 keys collected by our tracking system amongst all different botnets is surprisingly small, at around 40. This makes it pretty easy to decrypt any downloaded components without even needing to analyze the sample. It is interesting to note here that the same RC4 key is used to encrypt both sample strings and network communication, but reversed for the latter.

In terms of C&C communication, all the samples we analyzed were using Google's DNS infrastructure directly to resolve the C&C domains. Version 2.06 is trying to resolve the C&C server IP address using raw UDP sockets to 8.8.4.4:53. If it is unsuccessful, it first falls back to the DnsQueryA() Windows API and second to the gethostbyname() API. Version 2.10 hooks GetAddrInfoW() and all calls to it are resolved using raw UDP packets to 8.8.4.4:53 with fallback to the original GetAddrInfoW() API if unsuccessful.

New persistence mechanisms

In this section we cover two plugins that appeared this year and that we believe are an attempt to prevent takedown operations like this one from succeeding, by providing a side-channel communication to the botmaster. This behavior has also been discussed here [4].

The first one is a USB spreader while the second implements a fileless attack through a downloader stored in the registry that is launched via a PowerShell script at startup.

USB spreader – Win32/Bundpil.CS

This plugin is able to hook DNS API functions, tries to spread through removable media and uses a DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm) to download additional data.

There is one thread that scans for inserted removable media and, if it finds any, puts a copy of the malware on it. The other functionality of this plugin is to hook DNS APIs and replace specific domains by a hardcoded one. For example, one sample we analyzed was redirecting any requests to these old Wauchos domains:

- designfuture.ru

- disorderstatus.ru

- atomictrivia.ru

- differentia.ru

to gvaq70s7he.ru.

There is also a DGA component to this plugin that will try to connect to the automatically generated domain to download additional data to the compromised system. The DGA algorithm pseudo-code can be found on our Github page. The URLs it tries to reach match these patterns:

- <dga_domain>.ru/mod

- ww1.<dga_domain>.ru/1

- ww2.<dga_domain>.ru/2

We were able to download a binary blob from this DGA scheme. What we obtained was an encrypted blob starting with ‘MZ’. The plugin will remove these two bytes and store the blob directly to the Windows registry.

The main Wauchos bot will then decrypt the RC4 encrypted payload, decompress it with aPLib and load it as a regular plugin. Note here that the same RC4 keys used to encrypt the plugins are used for this process. The binary we obtained this way was an updated version of the USB spreader. We therefore hypothesized that through DNS hooking, it would be possible for botmasters to regain control of their bots by downloading a fresh version of this module from a domain they control, which will then redirect the hard coded-domains in the main Wauchos binary.

Downloader

The last plugin we want to talk about is a small downloader using a DGA to reach out to URLs like these, depending on the version:

- <dga_domain>.ru/ld.so

- <dga_domain>.ru/last.so

- <dga_domain>.ru/nonc.so

It is used to download a binary blob that it stores in the registry. This binary blob can be decrypted with the RC4 key contained in the main Wauchos payload.

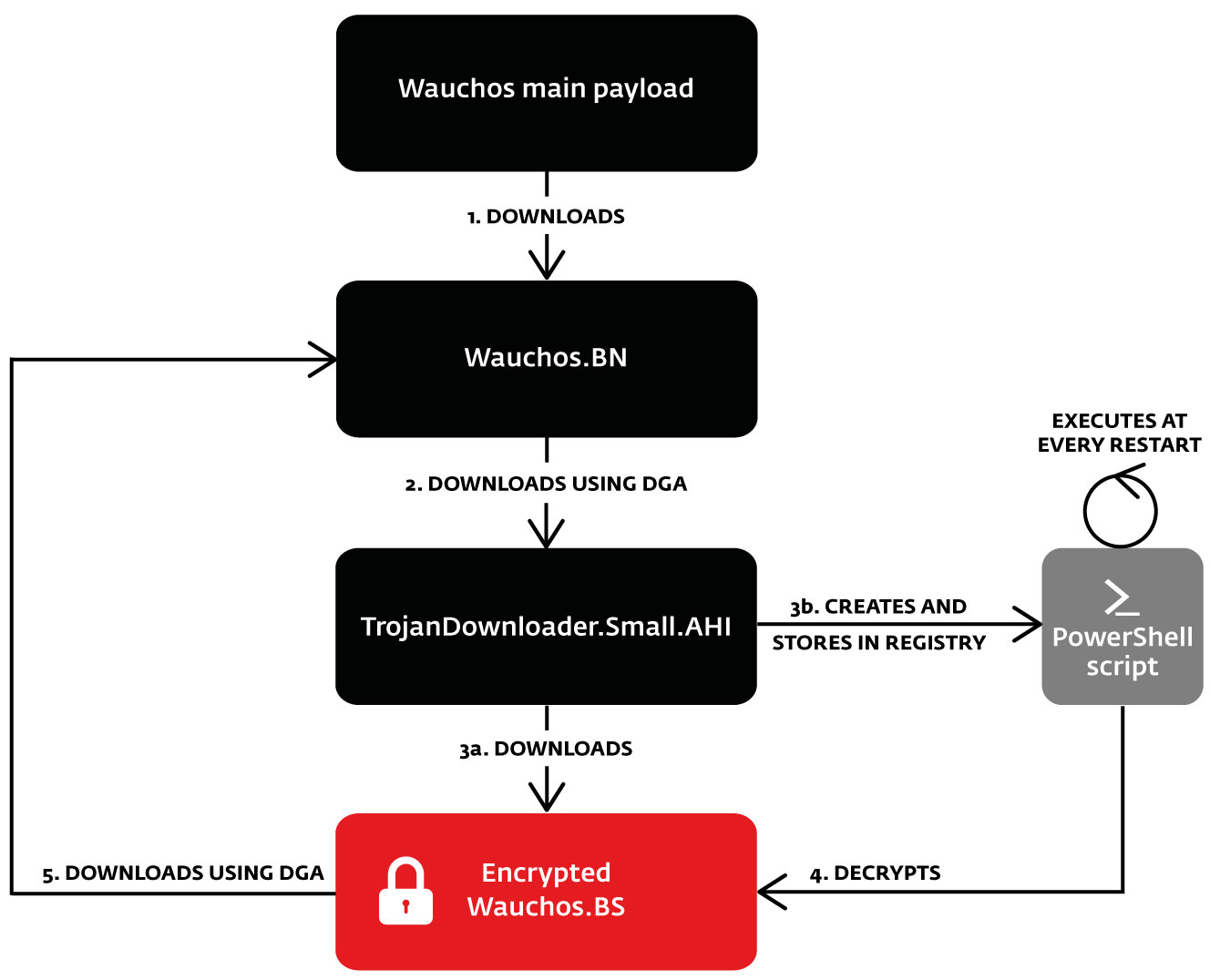

One of the malware variants that was downloaded by this plugin is another downloader detected as TrojanDownloader.Small.AHI. This malware is particularly interesting as its sole purpose is to download an updated version of the downloader plugin and store it encrypted in the registry, but with a little twist. It also adds a run key with a PowerShell script that decrypts and executes the encrypted binary from the registry key each time the machine is started. Right now, this binary is merely updating itself. However, its DGA could be used as a secondary communication channel to download a new payload and regain control over bots, should someone try to take them over. Figure 7 shows the overall process.

It is interesting to note here that we have also seen Necurs.B being downloaded through DGA and through this plugin. However, the vast majority of downloads we saw were for Win32/TrojanDownloader.Small.AHI. In fact, the latter malware has been seen numerous times, according to our cloud statistics. Interestingly, we saw a lot of activity in August 2016 for this particular module, via our crawler, but nothing since then. We did not investigate further to try to determine whether we were just blacklisted or if they only tested this feature for a brief period of time.

Conclusion

Wauchos is an old botnet that has been reinventing itself through the years. Its command and control infrastructure is one of the many that ESET tracks. This information is vital in order to keep track of changes in malware behavior and to be able to provide actionable data to help with disruption and takedown efforts.

Wauchos uses old tricks to compromise new systems. Users should be cautious when opening files on removable media, as well as files they receive through email or social media. If you believe that you are infected with Wauchos, we have a free tool for you. ESET products currently detect thousands of variations of Wauchos modules along with the different malware distributed by the Wauchos botnets.

Special thanks to Juraj Jánošík, Viktor Lucza, Filip Mazán, Zoltán Rusnák and Richard Vida for their help in this research.

Hashes

SHA-1 |

Detection |

|---|---|

| CC9AC16847427CC15909A60B130CB7E67D2D3804 | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.B |

| BCD45398983EB58B33294DFE852B57B1ADD5117E | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.AK |

| 6FA5E48AD60B53761A42725A4B9EC12B85963F90 | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Small.AHI |

| 6D5051580DA73570944BBE79A9EA7F2E4D006699 | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos.O |