Ransomware is a major threat that keeps growing over time. According to Cisco’s recent midyear report, it dominates the malware market and is the most profitable malware type in history.

By now, it seems unlikely any regular reader of our blog does not already know something about ransomware. If you do not—or would like a great summary—you must listen to our podcast by ESET's distinguished researcher Aryeh Goretsky.

In short, ransomware uses an assortment of techniques to block access to the victim’s system or files, usually requiring payment of a ransom to regain access. Recently we have seen significantly increasing volumes of a particular type of ransomware known as crypto-ransomware.

In this article, we look at how crypto-ransomware employs encryption and analyze some of the mistakes made by cybercriminals over time.

Ransomware and encryption

Encryption is a key element of crypto-ransomware, since its entire business plan depends on the successful use of encryption to lock the victims’ files or file systems, and victims lacking recovery plans such as data backupss.

This does not mean that encryption is intrinsically evil. Actually, it is a powerful and legitimate tool employed by individuals, businesses and governments to protect data from unauthorized access. Just like any other powerful tool encryption may be misused, which is exactly what crypto-ransomware does.

Why does crypto-ransomware use encryption?

Crypto-ransomware intends to “kidnap” data – hence the name. Encryption grants confidentiality to data, allowing only those who have the secret key to retrieve or access the original content, making it a perfect match to the criminal's needs.

Once crypto-ransomware takes hold in a system, it starts changing files or critical file system structures in such a way that they can only be read or used by restoring them to their original state. This requires the use of a key known only by the cybercriminals operating the malware.

Misused in this way, data encryption and decryption is analogous to holding data hostage and then (maybe) setting them free. Thus, encryption is used as a means to capture the victims’ data and extort a ransom from the victims in order to release the seized data.

Encryption is also used to secure the communication between the malware and its command and control server (C&C), which will ultimately hold a key necessary either to decrypt data or recover the decryption key necessary to recover the files or file system to their original unencrypted form.

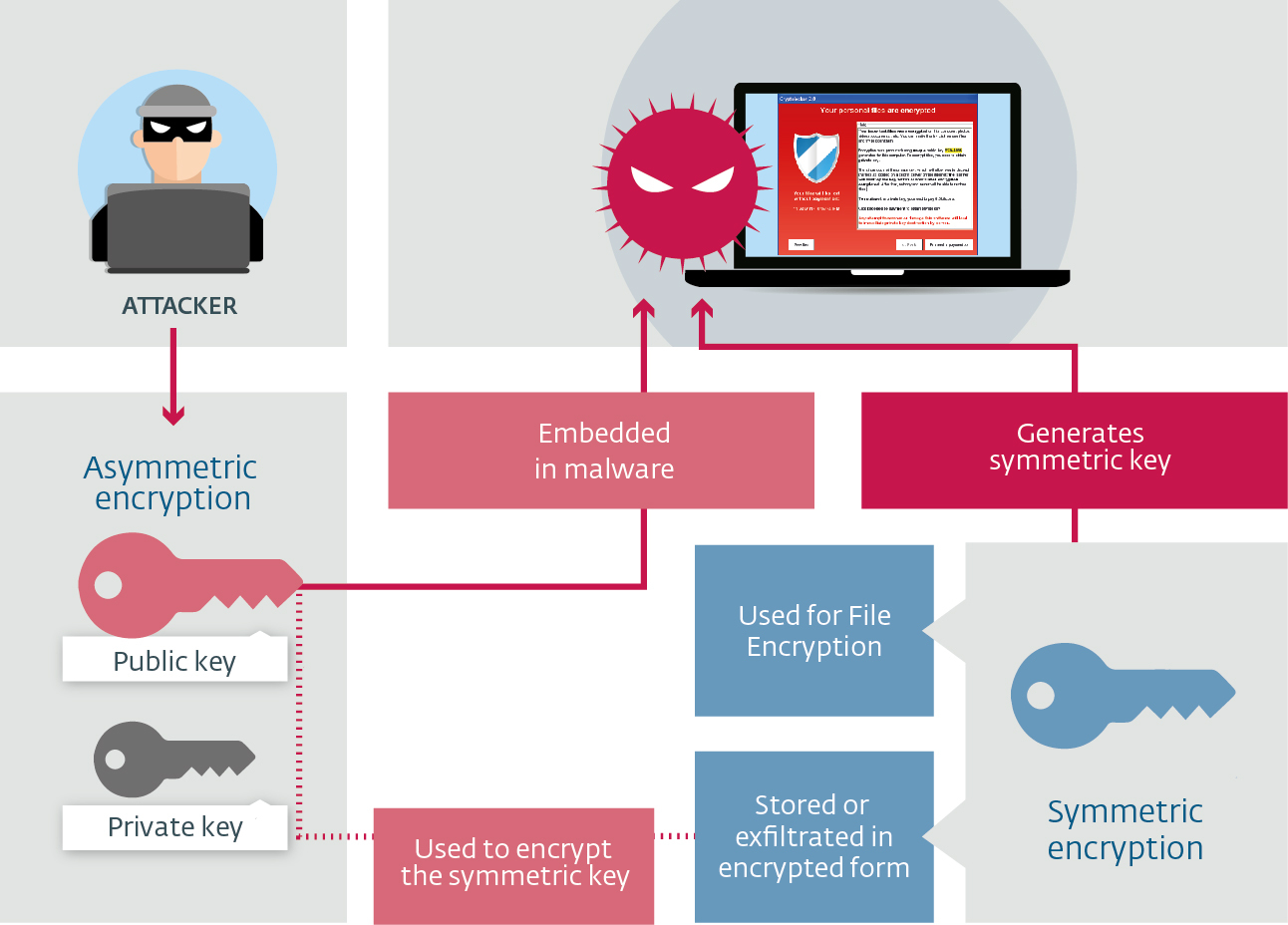

The main reasons for dual encryption are performance and convenience. Symmetric and asymmetric encryption are combined in order to get the best of both methods, in a technique that resembles a digital envelope.

In symmetric encryption, the same secret key is used in both encryption and decryption methods, whereas asymmetric encryption involves a private key, which is known only by its owner, and a public key, which may be known by anyone, where the encryption method uses the public key and the decryption method uses the private key.

Symmetric encryption is useful to crypto-ransomware because it is very efficient in terms of performance, allowing the malware to execute in reasonable time. On the other hand, asymmetric encryption is convenient because it enables the malware operator to (super-) protect only one private key regardless of the number of victims, otherwise the malware operator would have to keep a record of a (symmetric) secret key for each one of the victims.

Thus, to achieve high performance and keep the benefits of asymmetric encryption, crypto-ransomware usually uses symmetric encryption to encrypt the victims’ files and asymmetric encryption to protect the symmetric secret key.

Figure 1: Schematic of dual encryption in crypto-ransomware

Protection of the symmetric key varies, but mostly frequently the crypto-ransomware’s public key is embedded into the malware or fetched from the C&C server, then used to directly encrypt the symmetric key or to take part in its encryption process. After undergoing encryption, the symmetric key is often exfiltrated or stored on the affected system.

Communication with command and control servers: evasion and confidentiality

We can identify at least two main goals for deploying encryption in the communication between the compromised system and C&C: evasion and confidentiality.

Early families and versions of crypto-ransomware prioritized confidentiality for C&C communication. Newer families and variants have evolved and are adopting de facto encryption standards such as TLS.

This makes proactive network level detection much more difficult because it is harder to distinguish whether encryption is in place to secure legitimate communications, such as web-banking, or if it is used to disguise communication with the C&Cs.

When encrypted C&C communication is used, network-level detection requires the victim’s network to feature additional capabilities in order to inspect the traffic. As an example, TLS inspection can be provided by IDS/IPS in the network that stands in the middle of communication between the internal hosts and the remote servers. TLS inspection is also possible at the host level, depending on the capabilities of the antimalware suite in use.

In cases where the network does not have such a capability, malware using encryption to establish a connection with its C&C server will run undetected until the C&Cs are discovered and added to blacklists of malicious IPs and domains. Consequently, this type of protection is mostly reactive.

Encryption glitches in various ransomware families

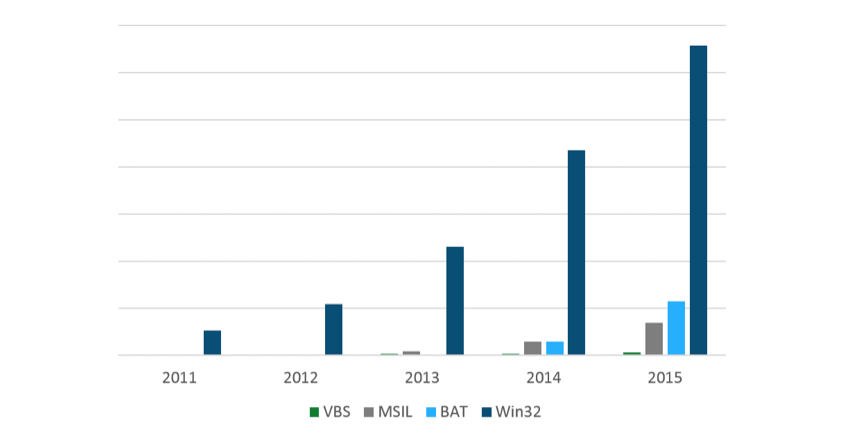

ESET has covered the evolution of crypto-ransomware previously, showing its growing prominence. The number of families, variants and targeted platforms has increased significantly since 2011.

Figure 2: Number of Windows file encrypting ransomware programs in the period from 2011 to 2015

The rest of this post takes a closer look at how encryption was used by four crypto-ransomware families at different stages of their evolution: CryptoDefense (2014), TorrentLocker (2014), the overwhelmingly successful TeslaCrypt (2015) and Petya (2016).

| Crypto-ransomware | Dual encryption |

|---|---|

| CryptoDefense | X |

| TorrentLocker | ✓ |

| TeslaCrypt | ✓ |

| Petya | X |

CryptoDefenseThe goal is to show how crypto-ransomware has evolved over time and analyze the mistakes made by cybercriminals along the way – from the silliest to the most sophisticated.

When CryptoDefense first appeared it was strikingly similar to CryptoLocker, which was one of the first crypto-ransomware families to make an impact. Notably, CryptoDefense had major implementation flaws in its C&C communication as well as in its file encryption process.

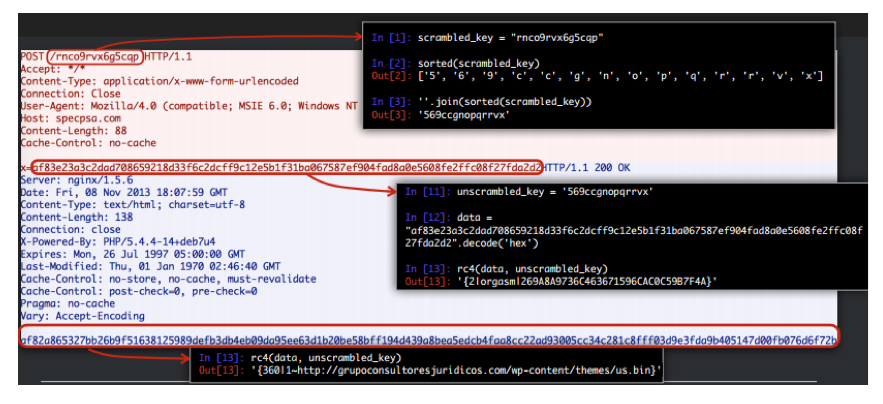

CryptoDefense’s C&C protocol is based on HTTP POSTs sent from the malware on the compromised host. In order to secure C&C communication, CryptoDefense employs obfuscation in the HTTP POST URL as a way to conceal the key used to encrypt the message body. The POST message carries the C&C protocol message encrypted with RC4 using the concealed key from the POST URL.

Figure 3: Decryption of CryptoDefense C&C protocol

Once C&C communication is intercepted, encryption notwithstanding, it can be easily deciphered. The request contains all the information required to recover the encryption key and unveil the underlying CryptoDefense C&C protocol, allowing the creation of network signatures that can prevent CryptoDefense’s file-encrypting payload from succeeding.

For file encryption the error is astonishingly similar. As a means of highlighting CryptoDefense’s mistake, let’s recall the basic operation of CryptoLocker:

- CryptoLocker (client) compromises the victim's system and notifies its C&C server with a campaign ID and a unique system ID

- C&C responds with an OK to acknowledge the client

- Client sends another request with the campaign ID and its unique system ID

- C&C provides the ransom note and the public key of a RSA-2048 pair uniquely-generated for that campaign ID/system ID combination. The private key never leaves the C&C server.

- Client acknowledges that it successfully received the ransom note and C&C public key, and that the encryption process is complete

In order to fix a deficiency found in CryptoLocker, in which encryption takes place only after successful communication with the C&C, CryptoDefense decided to generate keys for file encryption on the compromised host – skipping steps 3 and 4.

Nonetheless, a slight detail was overlooked by CryptoDefense’s authors. The encryption key, generated on the compromised host and used for file encryption, was never deleted. Thus, decryption can be easily accomplished by finding the private RSA key on the victim’s system and feeding it into the Windows API to decrypt the affected files.

So, CryptoDefense suffered twice from the same basic mistake: using encryption but giving away the key.

TorrentLocker

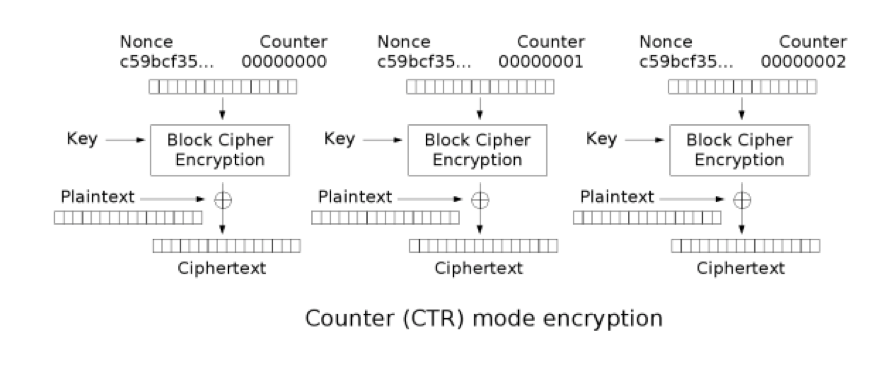

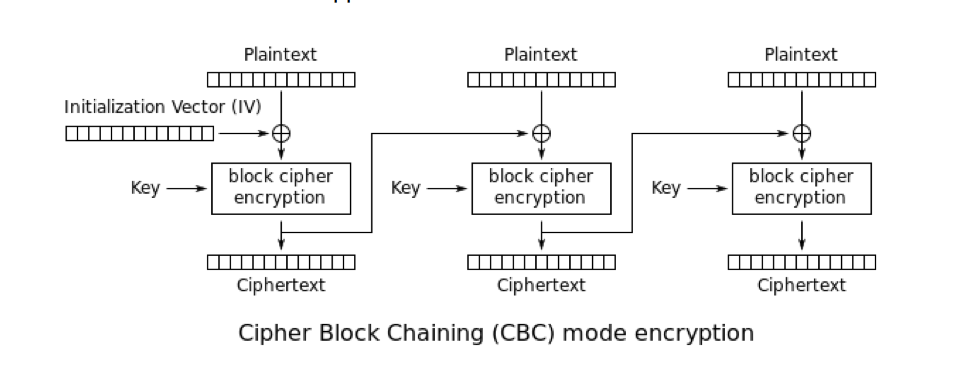

Early and flawed versions of TorrentLocker chose a very secure algorithm to encrypt the victim’s files: AES in CTR mode. Nevertheless, the manner in which the algorithm was used led to a remarkable weakness in the overall scheme.

AES is a block cipher, which means that it is able to encrypt blocks of a fixed size (16 bytes). However, messages can have lengths other than 16 bytes. This is where modes of operation come into play.

AES in CTR mode takes an initial value as a parameter, known as the Initialization Vector (IV), and uses it to stretch the key (which can have 128, 192 or 256 bits) up to the length of the plaintext (unencrypted content), becoming what is known as a keystream. Then the keystream is XORed with the message, mimicking the concept of a stream cipher.

The attack by early TorrentLocker versions was fairly simple: on the compromised system, TorrentLocker generated a 2MB keystream and proceeded with the encryption of the first 2MB segment of each file by XORing the segment with the keystream. In cases where files were smaller than 2MB, they were completely encrypted by the method.

However, this usage of AES-CTR mode was exactly analogous to the reuse of IV and key in stream ciphers, a rookie error in cryptography. Given a single encrypted file and its original unencrypted content, it is easy to recover the keystream and decrypt all the other encrypted files. Later TorrentLocker versions corrected the error by replacing the mode of operation from CTR to CBC, which will be addressed subsequently in the TeslaCrypt section.

Figure 4: Scheme of CTR mode of operation

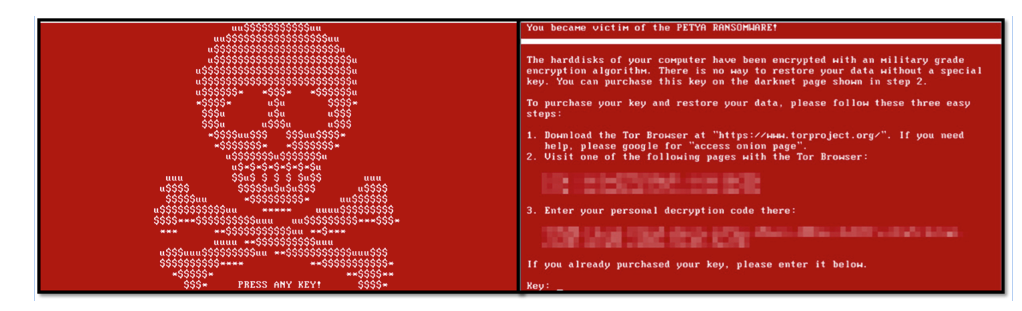

Petya

Petya took an approach different from that of other crypto-ransomware. Instead of encrypting files individually, it aimed at the file system. The target is the victim’s master boot record (MBR)which is responsible for loading the operating system right after system boot.

The cipher chosen by Petya’s developers was Salsa20, which belongs to the eSTREAM portfolio. The portfolio is the outcome of a project to promote the design of new stream ciphers to replace older ones like RC4. Petya’s adoption of Salsa20 denotes the evolution of crypto-ransomware into newer and more robust encryption algorithms.

When Petya is executed, it starts a two-stage attack intended to encrypt the MBR. The process of encrypting the MBR is well crafted; it starts by modifying the MBR and causing a BSOD to get the system rebooted, then it displays a fake CHKDSK screen while it performs the MBR encryption, and finally it reboots the system once more showing a blinking screen of a skull and the ransom message.

Figure 5: Petya skull screen and the ransom screen shown after pressing a key

Despite the scary ransom experience suggested by Petya’s skull and ransom message, it is still possible to undo the damage caused, due to several flaws in the way Petya handles encryption.

The most critical flaw, which enables decryption of the MBR after the attack is concluded, comes from the way Petya derives its encryption key.

To understand the key derivation flaw, we work backwards. We start by investigating how the recovery key, provided to victims after paying the ransom, is used in the decryption process. Then we explain how an implementation bug can be exploited so as to forego the need of knowing the entire recovery key to decrypt the MBR.

The charset for entering the recovery key is limited to 54 symbols and its length is fixed at 16 characters. Once the recovery key is entered in the ransom message screen, verification is performed to check whether the key entered is correct or not.

In the verification process, the recovery key entered is expanded to a 32-byte encoded key using a custom algorithm and is compared with a verification buffer in the sequence. If the encoded key matches the verification buffer, it is fed into the Salsa20 (strictly speaking Salsa10) cipher and the encrypted sectors are recovered.

Although the expansion method is executed on the recovery key, which doubles its size, the method does not add any extra entropy to the key because the expansion algorithm is deterministic. Thus, the security is bounded by 5416 different possible keys, which is equivalent to 92-bit security level (i.e. log2(5416) = 92.07) and far beyond, for instance, the 80-bit brute force capability estimated for the NSA.

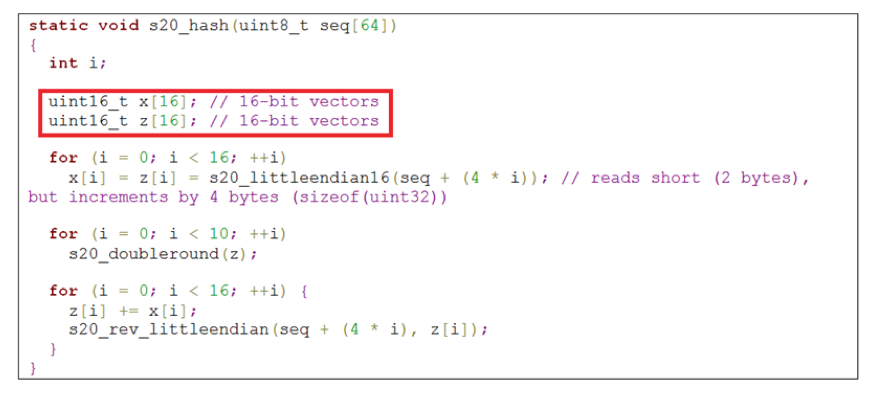

However, on top of the bounded entropy, Petya’s developers committed an implementation error in the Salsa20 core, which builds an array of 16 words containing constants, nonces, and the key from a so-called master table to be used during the encryption process.

Petya developers tweaked an existing Salsa20 implementation to support 16-bit architecture, but they missed a critical part. The reason for fiddling around with the Salsa20 implementation can be ascribed to the target execution mode. Petya is designed to run as a bootloader, which executes in 16-bit Real Mode on all x86 processors.

In order to build the array, two copies of the master table are created in little-endian format. Petya’s developers changed uint32_t variables to uint16_t (Figure 6) to address 16-bit architecture word size. However, they neglected to adapt the new word size while looping over the master table in Salsa20 core, so that 2 bytes are read and the offset for the next read is incremented by 4 bytes.

Figure 6: Petya development error in tweaking Salsa20 for 16-bit architecture

For this reason, only half of the key is actually applied for key derivation in Salsa20. This reduces the security level of the overall Petya encryption from 92-bit to 46-bit security (i.e. log2(548) = 46.04), which it is feasible to break within seconds using brute force even for standard computers.

TeslaCrypt

It is not by chance that TeslaCrypt has been one of the most successful crypto-ransomware families so far. The use of encryption is carefully handled and the choice of algorithms indicates that TeslaCrypt’s developers have some crypto-savviness.

TeslaCrypt uses AES-256 for file encryption; however, unlike the flawed version in TorrentLocker, it uses CBC as its mode of operation.

In CBC mode, each ciphertext block (fixed-size chunk of the encrypted message) is fed as the IV into the encryption of the next block and all the blocks are encrypted using the same key. Therefore there is no keystream or any analogy with stream ciphers, which renders the procedure used against the flawed TorrentLockers inapplicable here.

Figure 7: Scheme of CBC mode of operation

The AES key is encrypted using an EC-ElGamal-like algorithm and sent back to the C&C. The choice of Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) over RSA is very convenient for evading detection, since ECC results in shorter ciphertexts and takes less time to execute.

Nonetheless, the TeslaCrypt v2.2.0 (a.k.a. TeslaCrypt v8) developers committed a less trivial mistake. As reported by BleepingComputer and analyzed by Talos, the recovery key (RK), intended to protect the encryption key that is used for file encryption during the attack, is generated as the multiplication of the shared secret key (C2K), established with C&C, and the private key used to encrypt the files (FK).

RK = C2K * FK

The recovery key is stored on the compromised system and allows the recovery of FK when C2K is known. However, the TeslaCrypt v2.2.0 developers incorrectly assumed that they could avail themselves of the hard problem underlying RSA: factorization.

After decades, researchers have not been able to discover an efficient algorithm to calculate the prime factors of a given number (as large as the ones used in RSA). Yet, this does not mean that factorization could not be taken forward at all.

The recovery key was not long enough to make a factorization attack unfeasible. Hence, brute-force attacks turned out to be a way to find the file encryption key and finally decrypt the files to restore their original form.

Can encryption be used against crypto-ransomware?

It has been asked whether it is true that crypto-ransomware does not encrypt encrypted files. The answer is “yes and no”.

It is obviously possible to encrypt any encrypted data. As a matter of fact, this is the core idea in onion routing. In brief, onion routing is designed for privacy and conveys data through a circuit of routing nodes. Say that the circuit is composed of three nodes, so when the user wants to access some website the request will be encrypted with node key three (exit node), encrypted again (the already encrypted content) with node key two and again using node key one (entry node). As the request goes through each node, it gets decrypted using the key of the current node, in such a way that only the exit node will have the original request, prior encryptions brought off by the onion routing process. The exit node makes the request on behalf of the user and sends the response back using a similar encryption process as was applied to the request.

For the sake of efficiency and precision, crypto-ransomware usually decides whether to encrypt a file depending on its filename extension; for instance, the list for TorrentLocker by 2014 is available here. If the extension matches a predefined set of extensions it is encrypted, otherwise it is not.

On the other hand, encryption tools often append some pre-determined new extension to the filename when the file is encrypted. It is an interesting fact that we have not seen any crypto-ransomware targeting encryption tools yet.

As a consequence, if the system is compromised by some crypto-ransomware that does not target the encryption tool in place, files encrypted by the tool will, just by good fortune, not be encrypted by the malware. Keeping this in mind, a useful feature to add into encryption tools is extension randomization, which could be as simple as allowing the user-to define a scheme during installation.

Extension randomization does not add any performance overhead nor require great design changes in encryption tools, but it could be to some extent effective against crypto-ransomware.

In order to target encrypted files, crypto-ransomware developers would have to select/find the encrypted files at the time of execution or abandon the idea of extension-based selection, evolving their attacks to avoid selecting critical application/OS files for encryption that could damage the system and make the attack fail before accomplishing its aims.

This is why the use of legitimate file encryption tools to encrypt your files might serendipitously lessen the impact of crypto-ransomware; nevertheless crypto-ransomware mitigation should not be totally reliant on encryption tools: backup and other proactive measures are even more important.

Avoid and combat crypto-ransomware

We published a post providing many good tips that can help you avoid crypto-ransomware. Here are some of these tips:

- Use a reputable antimalware suite and enable proactive measures like HIPS and anti-phishing protection

- Practice a safe behavior: show hidden file-extensions and do not open links and messages from unknown sources

In the event, despite all the care taken, you cross paths with crypto-ransomware, you will want, in advance, to:

- Have a recent, validated, offline backup of your files, so schedule backups to frequently execute

- Avoid mapping backup folders onto your computer. Crypto-ransomware may end up encrypting backups in folders on USB devices, cloud storage and any other place that is accessed as folders in the system

As a last resort, you can try to decrypt your files with tools made available by security researchers for some specific crypto-ransomware families. ESET includes decryption tools for several crypto-ransomware families and variants to retrieve encrypted data without having to pay the cybercriminals.

Additionally, a recent initiative by the National High Tech Crime Unit of the Netherlands’ police and Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre, in collaboration with IT security companies, also provides tools to help victims of crypto-ransomware.