Introduction

This is a look back at a presentation I made a few years ago, extensively revised to coincide (roughly) with the sixth anniversary of the time that Stuxnet (in particular) first came to our attention.

Stuxnet had, however, been around for quite a while before that. The fact that security firms hadn’t noticed it is probably accounted for by the fact that the first version only found its way onto very few machines in a geographically limited location.

The presentation drew heavily, of course, on the report by Alexander Matrosov, Eugene Rodionov, Juraj Malcho and myself on Stuxnet, which you can find here.

This present document isn't intended to be a deep dive into more contemporary SCADA and infrastructure issues. It's more a case of asking: “What happened, and what changed afterwards?”

Acronymically speaking

- SCADA: Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition – coordinates processes

- DCS: Distributed Control System – controls processes in real-time

- ICS: Industrial Control Systems

- CNI: Critical National Infrastructure

- RTU: Remote Terminal Unit

- PLC: Programmable Logic Controller - cheaper than an RTU

I may make reference to some of these in the course of this article, but I’m not focusing on SCADA particularly. Instead, I’m more concerned with generic infrastructure as a potential target for malicious action.

What was the fuss?

Stuxnet and its lesser siblings dominated the threat landscape in 2010. Why all the interest?

- Its unusual complexity and technical sophistication.

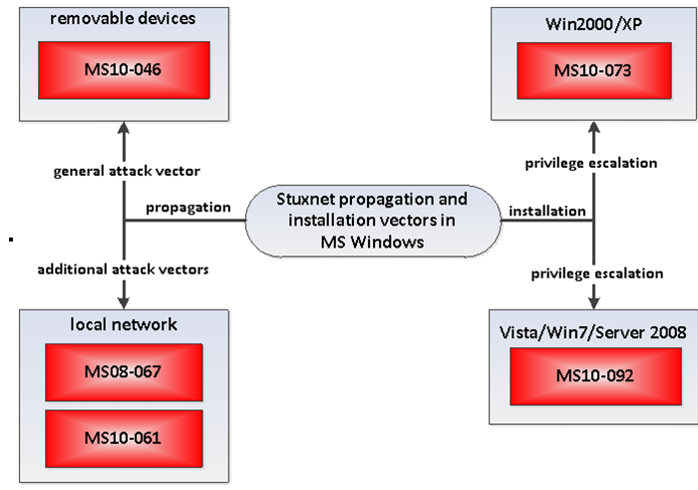

- An unusually generous array of multiple exploits of zero-day or little-known vulnerabilities: MS10-046, MS10-061, MS10-073, MS10-092 + MS08-067, 0-day, 0-tolerance, and I haven’t even listed the Siemens hard-coded 'password'.

- Its ‘Tiger Team’ approach to implementation.

- Signed with (stolen) certificates from Realtek and J-Micron, while a subsequent flurry of fake certificates approved by Comodo suggested that signing was an issue likely to come up again and again. (As it has, if not to the extent that you might have expected at the time.)

- It was targeted (at a time when the term APT was becoming increasing ‘buzzy’), though I’d actually describe it as semi-targeted. Still, the payload certainly had a very specific, potentially critical installation in view.

- It included a mysterious hardware-specific payload in a novel language specific to an ICS: certainly a change from Visual Basic and Delphi, languages with which all malware analysts are very familiar. And because of the specialized nature of the context in which it executes, it took a long time to ascertain what it actually did, even with specialist help.

Nothing exceeds like Stuxnet

The version that calls itself internally 0.5 may have been operational as early as 2005.

The 2009 version stayed well under the radar, but had limited scope and exploited a limited range of vulnerabilities: MS08-067; MS10-061; MS08-025 (win32k.sys!NtUserMessageCall). It used autorun.inf to spread – an attack still possible for some systems even in 2016.

There was a significant upgrade in January 2010. Another driver was added, signed by Realtek Technologies, and several new zero-day vulnerabilities were added: MS10-046; MS10-061; MS10-073; MS10-092. It’s unusual to see that many zero-days in a single malicious program. Someone was getting serious.

Stuxnet Vulnerabilities

Let’s take a look at one or two of those Liquorice Allsorts zero-days. Multiple entry points, multiple types of vulnerability.

- MS10-46: not an Autorun.inf attack, though it worked very similarly but (for a while, anyway) more effectively - disabling Autorun didn’t stop the infection (for that you had to cripple Windows Explorer till the patch came out). It was picked up later by umpteen short-life bottom feeder malware variants. Any .LNK file could exploit it when displayed in windows explorer and the icon for a .LNK file was loaded from a Windows Control Panel file (actually a DLL, effectively).

- MS08-067: self-distribution over the network installing a dropper through shared folders. It scanned network shares c$ and admin$ on the remote computers and installed a dropper there with the name DEFRAG<GetTickCount>.TMP, and scheduled a task to be executed on the next day.

- (MS10-061): A privilege escalation vulnerability in Window Spooler allowing a remote Guest account to write into the %SYSTEM% Machines with file and printer sharing turned on were vulnerable to the attack.

- (MS10-073) A zero-day in sys escalated privilege level up to SYSTEM, which enabled it to perform any tasks it liked on the local machine. To perform this trick, Stuxnet loaded a specially crafted keyboard layout file, making it possible to execute arbitrary code with SYSTEM privileges.

- MS10-092: used a vulnerability in the Task Scheduler service to escalate privilege: in fact, that attack lived on for a while in the TDL4 bootkit. TDL4's implementation doesn't essentially differ from that of Stuxnet's code. The rootkit created a legitimate task by means of the interface available in the system, then read the xml schema that corresponds to the task directly from the file in the Task Scheduler folder, and then modified it.

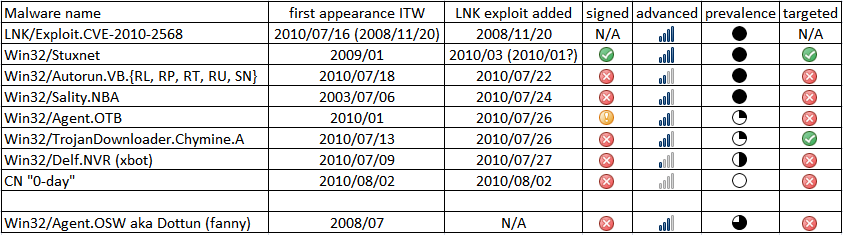

MS10-046 related malware and its evolution

More is not always more. Here are some of those MS10-46 bottom feeders:

SCADA, Siemens and Stuxnet

As of March 11th, 2011, Siemens was reporting 24 industrial sites with (unspecified) infected systems.

There were earlier reports of 14 or 15 SCADA sites affected by the direct infection of PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers). While the use of these vectors has increased the visibility of the threat, it also facilitates access to sites where “air-gapping”, as a generic defense, was seen as decreasing the need for automated technical defenses like antivirus and system updating and patching. This is not a minor consideration, since the withdrawal of support from Windows versions earlier than Windows XP SP3. One thing that became very clear to me during certain discussions was that Microsoft was not rushing to patch unsupported systems so as to save necks at SCADA utilities using obsolete Windows versions.

This attack used a further vulnerability categorized as CVE-2010-2772, relating to the use of a hard-coded password in those systems allowing a local user to access a back-end database and gain privileged access. Not only was the password exposed to an attacker through reverse engineering, but the system would not continue to work if the password was changed.

Signed drivers and stolen certificates

Both companies (Realtek Semiconductor Corporation and Jmicron Technology Corporation), whose code signing certificates were used by Stuxnet, had offices in Hsinchu Science Park, Taiwan. That may suggest physical theft, but the certificates may have been bought from another source. For instance, the Zeus botnet was known to steal certificates, though its focus was on banking certificates. The file jmidebs.sys functions in much the same way as the earlier system drivers, injecting code into processes running on an infected machine. Maybe the attackers changed their certificate because the first one was exposed, or were simply using different certificates for different cyberattacks. Either way, they obviously had significant resources to draw on. The modular architecture that characterizes the Stuxnet malware suggests the involvement of a fairly large and well-organized group.

Tyger, Tyger - maeT regiT

Stuxnet has the hallmarks of a collaboration between several individuals or groups with specialist expertise – a (reverse) Tiger Team, if you like – yet its cover was blown by its promiscuous dissemination through the Autorun-like LNK vulnerability, a vector that automatically raised its chances of being detected heuristically. That may suggest the following …

- A team where no-one had specific experience in the malware field. Maybe that's understandable in a team put together under the auspices of a government or governments, if that’s really what happened.

- Or the malware had already been so effective that staying under the radar wasn't a major concern (the LNK version of Stuxnet was not the first version).

- Or someone intended to send a message to Iran and the rest of the world about the capabilities of certain agencies and states. After all, much has been made of the "clues" in the code. However, even in 2016 I still haven't seen conclusive evidence as to exactly who orchestrated that “message”, or planted those clues. Misdirection is a standard tool for diplomats and politicians, as well as for espionage.

Ironically, my own initial involvement with Stuxnet was partly due to being pulled into a hastily assembled US-based Tiger Team incorporating SCADA sites, law-enforcement, and one or two security vendors.

Some of the code looks as if it originated with a "regular" software developer with extensive knowledge of SCADA systems and/or Siemens control systems, rather than with the criminal gangs responsible for most malcode. Or, come to that, the freelance hacker groups – sometimes funded by governments and the military – we often associate with fully targeted attacks. Or was it a formally-constituted, multi-disciplinary “tiger team”.

On the other hand, wide propagation prevented the malware from remaining “below the radar”. This may signify misjudgment or a miscommunication at some point in the development process.

On yet another hand, it may simply mean that the group was familiar enough with the modus operandi characteristic of SCADA sites to gamble that Stuxnet would hit enough poorly-defended, poorly-patched and poorly-regulated PLCs to gain them the information and control they wanted. The clustering of infections in a country to which Western countries were reluctant to export, resulting in uneven (at best) licensing, may have had an impact on patches and updating.

Target, Target (… burning bright …)

Stuxnet at least suggested how much can be conceived and achieved using massive semi-targeted attacks. Why semi-targeted? Because while the payload is plainly focused on a control system, the malware’s propagation was promiscuous. Criminal (and nation-state funded) malware developers have generally moved away from the use of self-replicating malware towards trojans spread by other means (spammed URLs, PDFs and Microsoft Office documents compromised with zero-day exploits, and so on). Truly targeted and non-replicative malware (aimed at individuals, often using customized social engineering as well as customized code) is much harder to catch.

Stuxnet’s usefulness in terms of payload delivery could have been depleted (a little nuclear joke there) by public awareness and the wider availability of protection.

What was the real game-changer?

But what are the real implications behind the hypefest and the barrage of sheer speculation about who created it, and why? The real game-changer here is not the malware, interesting though it (still) is to specialists and the media alike, but what it says about its potential targets and the state of security before and after the attack became public knowledge.

It’s not the speculation about origin and targeting of the malware, or even the painstaking analysis of the binaries, but the way in which critical installations work, and their relationship with the wider world of security. What does it tell us about the state of CNI (Critical National Infrastructure) security, nationally and globally? Where does the security industry fit in a world of cyber-everything? (cyberespionage, cyberterrorism, cyberwarfare, cyberhysteria and other cyberbuzzwords.)

The Target

There is evidence suggesting that equipment used for uranium enrichment in nuclear facilities was the original target. This paper, Did Stuxnet Take Out 1,000 Centrifuges at the Natanz Enrichment Plant?, by David Albright, Paul Brannan, and Christina Walrond, goes into a great deal of detail about the equipment, even if it’s inconclusive about exactly what Stuxnet did. There are lots of other relevant links at the Institute for Science and International Security web site (once you get past the Google ads). The equipment targeted by Stuxnet required a very specific configuration: a PC running Siemens WinnCC software connected to an S7 Simatic PLC equipped with specific CPUs, Profibus communications module(s), and a number of specific frequency converter drives operating at a speed of 807-1210 Hz.

The Fantasy

This didn’t put a complete end to the speculation, of course. Sky News discovered that the Sky really is falling, claiming that the “super virus” is being traded on the black market and “could be used by terrorists”. In fact, given the amount of detailed analysis that’s already available, no-one with malicious intent and a smidgen of technical skill would need the original code (or rather the disassembled code that had already been around for quite a while) in order to make use of it.

However, it was suggested that possession of “the virus” in whatever form had alarming potential:

- “You could shut down the police 999 system."

- “You could shut down hospital systems and equipment.”

- “You could shut down power stations, you could shut down the transport network across the United Kingdom.”

These assertions clearly owed little to the PLC code actually discussed in competent analyses. While it might be possible to do all these things, that would require very extensive recoding and by now, a completely new set of zero-days.

Changing the game

Less hysterically, Charles Jeter asserted that:

"The disruptive threat of Stuxnet is not found within the malware, it’s in the entire process and the proof of concept. This malware attack should be thought of as a template to an intelligence operation, not merely a scrap of software code."

Ralph Langner asserted that: "The biggest collateral damage, however, emerges from the cost of dealing with post-Stuxnet malware, which copies attack technology from Stuxnet."

Is that really so? It depends on what kind of copycat code you’re expecting. Any anti-malware program should have been detecting the base code for over half a decade.

Earlier versions stayed under the radar for many months (maybe years in the first instance) because distribution was extremely limited, to an industry sector where tight anti-malware protection is not always seen as necessary or even possible. (Iran seems to have had particular problems arising from software import restrictions and licence enforcement.) But the versions that hit the headlines, though often described as targeted, while actually targeted in terms of the payload (what it did and where it activated), was much less so in terms of distribution. Hence the initially wide geographical dispersion of reported infections, though the clustering in Iran turned out to be highly suggestive.

For the security industry, the real challenges were in disentangling exactly what the malware did. Most AV companies don’t have ready access to specialist SCADA systems, or the specialist expertise to analyze the PLC code. And in any event the code doesn’t tell you everything about the target. At ESET, we concentrated more on analyzing the zero-day attacks, from which we learned a great deal. This is important because the bad guys also learned a lot.

Fortunately, you don’t have to know every detail of the payload to detect malware, but the complexity of the attack made detailed analysis very time consuming, where it was possible at all. While close analysis of such exploits isn’t usually necessary in order to detect specific malware, it does enable us to do a better job of developing generic and proactive detections that lessen the impact of future malware using similar attack techniques.

Conclusion: The aftermath

I was asked at the time:

Do organizations and governments need to re-evaluate their security?

The only rational answer is 'constantly'. But not just because of Stuxnet. The threat from direct re-use of Stuxnet SCADA-specific code in unrelated attacks (as opposed to more generic re-usable binary techniques) has been exaggerated – but sound security isn’t just a one-off implementation: it’s an ongoing process to which continuous review of security posture and risk assessment are integral. Evaluating and adapting (where necessary) to new risks, internal and external, is part of the process. That’s Security 101.

What does Stuxnet mean for the computer security and control systems industry?

There are difficulties for some sites where protective measures may involve taking critical systems offline. While there are obvious concerns here concerning SPoFs (single points of failure), the potential problems associated with fixing such issues retrospectively should not be underestimated.

Stuxnet brought to light some problems with SCADA and ICS that aren’t necessarily directly relevant to Stuxnet’s own targeting. There are some scarily bright people in that space who understand both security and their own specialism very well, but there are also a lot of cut-rate installations relying on obsolescent control systems and security by obscurity. A critical installation doesn’t usually have direct connection to the internet, but infection is possible via connected systems that aren’t in themselves critical. Think USB, for a start. (The people behind Stuxnet did …)

How has it affected governments and the military?

The kind of utility that Stuxnet appears to target is important, but there’s a lot more to a critical national infrastructure than nuclear reactors. The message is not so much that a nuclear program can be derailed (or at least impacted) by malware. (Though it remains a subject for debate as to how true this was of Bushehr or Natanz.) It’s that somebody thinks it’s worthwhile to put together teams to orchestrate attacks on critical sites using malware, rather than just hiring a few samurai to launch targeted attacks, as happened a great deal in the early noughties. The next such attack may be focused on a very different sector and use entirely different exploits. but it’s unlikely that there will never be another attack of this type, even if you believe Stuxnet was the first.

Political and military strategists cannot ignore that potential.

Do traditional perimeter defenses provide a complete answer to infrastructural attacks?

A year after Stuxnet, Luigi Auriemma found 30-50 vulnerabilities in four SCADA products made by Siemens, Iconics, 7-Technologies and Datac, some remotely exploitable. Since then, it’s become increasingly common for researchers to disclose vulnerabilities only to subscribers to their audit (and other) services. Well, I guess we all have to make a living … Bottom line: you don’t have to be a specialist to start finding holes, and infrastructural weaknesses continue to be reported on specialist lists.

SCADA pain points

Critical control systems are often left unpatched, either because it is difficult to fully test the patch and ensure that it will not affect normal operations, or, in the case of systems not connected to the internet, because it’s assumed that those systems are not subject to outside influence and are therefore protected. Industrial controls engineer Jake Brodsky made some very pertinent comments in response to a blog article I wrote at the time.

While agreeing that strategically, Siemens were misguided to keep hardcoding the same access account and password into the products in question, and naive in expecting those details to stay secret, Jake pointed out, perfectly reasonably, that tactically, it would be impractical for many sites to take appropriate remedial measures without a great deal of preparation, recognizing that a critical system can’t be taken down without implementing interim maintenance measures. He suggested, therefore, that isolation of affected systems from the network was likely to be a better short-term measure, combined with the interim measures suggested by Microsoft for working around the .LNK and .PIF issues that were causing concern at the time.

Additionally, after it was discovered that Stuxnet was exploiting default passwords, the SCADA system vendor issued guidance to its customers requesting that they refrain from changing default passwords because they were hard-coded into the products and could cause their systems to fail if changed. This recommendation contradicted the traditional practice of changing default passwords upon installation of commercial products.

Security practitioners in that space found themselves in the challenging position of having to decide which risk was greater, knowing that either option could cause significant service outages to critical systems. Of course, practitioners in other spaces that aren't considered to be SCADA – some healthcare facilities for instance – find themselves uncomfortably perched on similar dilemmas.

Future Shock

Everything is connected, directly or indirectly. Issues like power failures and maintenance problems on infected sites generally generate more heat than light in terms of PR exposure. But of course a maliciously engineered disaster is entirely possible. Otherwise, a lot of movie scriptwriters and security prognosticators would be out of work.

Organizations need to continuously re-evaluate baseline controls. Computers not connected to the internet do not usually operate in a complete vacuum. We cannot ignore the potential consequences of an attack that can traverse the air gap to segmented networks.