The Target hack that was revealed one year ago today brought new levels of awareness to the problem of cybercrime. Today we review the case and its impact. To go straight to the lessons learned, click here.

The Big One: Target

"Nationwide retail giant Target is investigating a data breach potentially involving millions of customer credit and debit card records, multiple reliable sources tell KrebsOnSecurity." With that sentence, published on December 18, 2013, Brian Krebs opened the door on what remains, exactly 12 months later, the most widely felt cybercrime that American consumers have yet experienced. (Sure, the ongoing attack on Sony Pictures is a big deal too, but it is not directly impacting our credit and debit cards.)

The next day, December 19, my colleague Lysa Myers posted what was to become one of the most visited pages on We Live Security: Target breached: 5 defensive steps shoppers should take now. At that time we did not know we would need to reiterate the same advice many times over as big name hacks followed Target into 2014.

The Target hackers stole 40 million payment card records and 70 million customer records in the middle of the busiest shopping season of 2013. In fact, this was not the largest number of American credit and debit cards ever compromised in a cybersecurity breach; that dubious record is still held by the Heartland Payment Systems hack in 2008 (130 million), followed by the TJX breach in 2007 (94 million).

What put the Target breach into another league is the fact that so many people had shopped there so recently. The breach happened during the 2013 holiday shopping season and Target is #5 in the National Retail Federation’s Top 100 Retailers list, based on sales (TJX is #19). Another psychological factor that has not helped Target: being the first in a long string of hacks affecting well-known brands, from Neiman-Marcus to PF Chang and Dairy Queen. By the time we learned of another top five retailer attack -- The Home Depot is #5 and exposed 56 million cards -- Americans were getting "breach fatigue" and Target had become synonymous with a "new normal" in consumer consciousness. People were saying "all this hacking, you know, Target and so on."

Lessons Learned

So what have we learned from this year-long string of criminal payment card hacking? Here are seven lessons for both companies and consumers. The good news is this: if we all heed these lessons we can improve our ability to thwart cyber criminals.

1. We need to pay attention: to accounts and networks

For consumers, paying attention means monitoring accounts; for companies it means monitoring networks. Many bank and credit card accounts can be configured to send you a message when transactions occur (I get mine as a text message on my phone). This is your best chance of limiting damage to your account from someone who has obtained your card data.

At the same time, companies need to be monitoring activity on their computer networks for anything suspicious. Banks already monitor payment cards for patterns of activity that may be fraudulent, like you trying to pay for lunch in San Diego with a card that was just used to buy a TV in Minneapolis (which happened to one of my cards last year). But what about the networks within retail and restaurant chains? Responsible companies have deployed software to spot anomalies on their internal networks and servers, but that alone is not enough. The right procedures need to be in place AND followed for such monitoring to be effective (it is reported that network monitoring alerts were triggered by the criminal intruders at Target, but the response did not happen the way it should have).

2. Good security = good technology + good people + good leadership

This lesson applies to both companies and the tens of millions of American households that have become domestic network operation centers (home router and Wi-Fi access point plus laptops, tablets, shared storage, streaming media, smart TV, and so on). The lesson for companies is that the latest and greatest security technology won’t save them from the bad guys unless they also hire good security people, deploy them appropriately, and back them up with clear direction and adequate resources. Target had some good technology and some good people, but warning signs of a breach were missed and reaction times were not fast enough; two indications that security was not given the required level of priority within the organization relative to established and emerging threat factors.

On the domestic front, now is a good time to check your network technology. Are you still using the basic Internet router that your ISP supplied? Have you Googled its model number to see if there are any recalls, firmware updates, or other issues? Try checking your router for known UPnP vulnerabilities using Rapid7's tool and consider investing in a more capable router and wireless access point, one that has features labeled NAT and SPI. Make sure your endpoints, the devices that connect to the router, have firewalls enabled (Windows and Mac OS X both include basic firewalls but consider adding to that with a security product such as ESET Smart Security or Cyber Security Pro). And don't forget your home network users, family and friends who need to know the basic rules of cyber hygiene, like protecting each device with a password or biometric, choosing strong passwords, and thinking before they click on links in email. You can find a lot of useful tips here on We Live Security and at the National Cyber Security Awareness site.

3. Politicians are not doing enough to solve this problem

In January of this year the talk of Washington was: “We must do something about these credit card breaches!” That’s because a lot of politicians got an earful from unhappy constituents who had shopped at Target, long considered a low-risk activity. But did politicians do anything? I don't see much evidence that they did. More funds to the FBI or other law enforcement agencies to hunt down the data thieves? Not that I've seen, but please comment below if you know otherwise). We do know that politicians cut the budget of one agency that is crucial in America’s fight against identity fraud: the Internal Revenue Service.

One change to the payment card industry in America will start to appear in 2015, something that will make it harder to create fake payment cards out of stolen card data: the introduction of chip cards using technology known as EMV. However, this change was already on the books, driven by Visa and Mastercard, not elected officials.

So, whether you are a citizen or a company, you should probably make your feelings on cybersecurity known to politicians and government officials. Hopefully, you will demand that they do more to deter cybercrime.

4. Chip cards won't end cybercrime

It is true that the introduction of chip cards using technology known as EMV will make it harder to create fake payment cards out of stolen card data, but both companies and consumers need to know that this technology alone won't make cybercrime go away. Think of it like this: suppose you have been "earning" a nice living buying stolen card data online and using it to make fake cards that can be converted into cash or fancy consumer goods; now you find most stores are asking for chip cards, which are relatively hard to fake; what do you do, A. get a job or B. try your hand at some other crime? I think plan B is more likely to appeal to the criminally inclined, a phenomenon that is familiar to criminologists as crime displacement.

And the conversion to chip cards will not be immediate. There is an October 2015 deadline but it's complicated, as you can see from this statement by Mastercard's EMV expert, quoted by the Wall Street Journal:

"So if a merchant is still using the old system, they can still run a transaction with a swipe and a signature. But they will be liable for any fraudulent transactions if the customer has a chip card. And the same goes the other way – if the merchant has a new terminal, but the bank hasn’t issued a chip and PIN card to the customer, the bank would be liable."

Ask any experienced cyber criminal and they will tell you "confusion is a good thing"; so look for card hackers to probe retail and restaurant systems during the EMV conversion process. At the same time, expect other cyber crimes to emerge, potentially targeting companies, consumers, and even non-profit organizations, for theft of personal data records.

5. Cybercrime is a business for many people

As you can gather from Lesson 5 -- and hopefully both companies and consumers heard this in media coverage of the Target hack -- some criminal elements in cyberspace operate on standard business principles, like return-on-investment, supply-and-demand, and risk assessment. Expect these criminals to look for other ways to convert data to cash besides credit card hacking. Full identity theft will probably see an increase, using data such as Social Security Numbers to impersonate people and take out loans in their name, or file taxes for them (see this article on the $5 billion tax identity fraud industry). For a more complete education in the business of cybercrime read Spam Nation by Brian Krebs. It's about a lot more than spam and it reveals how the world of cybercrime evolved as a business.

6. Companies can do better

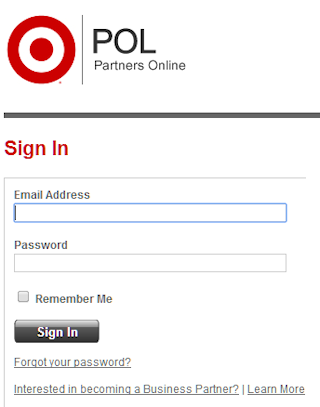

Criminals got into Target's systems by first hacking into the systems of another company, one that was a supplier to Target. Like many companies, Target offered its partners and suppliers a helpful online portal to manage their business dealings (see the sign in box on the right).

Criminals got into Target's systems by first hacking into the systems of another company, one that was a supplier to Target. Like many companies, Target offered its partners and suppliers a helpful online portal to manage their business dealings (see the sign in box on the right).

Unfortunately, it was possible to hop from that portal into the network from which the retailer's point of sale terminals were managed. That is considered a "Fail" in network security; there should have been no way that hop could happen. Hopefully, a lot of companies took a fresh look at their network architecture after these details of the Target hack emerged, plugging gaps like this.

The lesson here for consumers is that home systems may be targeted as a path to larger targets. One reason to check your home router for known UPnP vulnerabilities -- using Rapid7's tool for example -- is that criminals have been using that vulnerability to carry out distributed denial of service attacks from home routers, as described by Rapid7 here, and also by Akamai here.

7. Safe shopping is still possible

While cybercrime is currently an unpleasant and sometimes painful blight on society, it is still possible to shop in relative safely. Check out this advice from my colleague Lysa Myers Ready, set, shop: 10 top tips for a safe shopping season.

Here's wishing all our readers a safer and wiser 2015.