[Update: a PDF version of this article as a single document is now available here.]

Introduction

One of the earliest projects David Harley worked on at ESET was a paper on phishing with Andrew Lee A Pretty Kettle of Phish, published in 2007. They worked on a number of related papers subsequently, and the problem hasn't gone away (indeed, it comes up time and time again in our blogs).

In fact, according to the Anti-Phishing Working Group's most recent report, while the number of PCs infected by phishing malware was decreasing in the first quarter of 2012, the number of unique phishing sites flagged by the APWG reached an all-time high of 56,859 in February, with another all time high of 392 targeted brands in February and March.

In fact, according to the Anti-Phishing Working Group's most recent report, while the number of PCs infected by phishing malware was decreasing in the first quarter of 2012, the number of unique phishing sites flagged by the APWG reached an all-time high of 56,859 in February, with another all time high of 392 targeted brands in February and March.

However, like other threats primarily based on social engineering, phishing doesn't stay in one place for too long: it changes attacks and vectors. When that paper was first written, social media like Facebook and Twitter were much less used, whereas they're now routinely used as a channel for phishing and other attacks. Which means, perhaps, that ESET should consider revisiting the issue in a new or re-engineered paper, but in the meantime, here's a recap along with a discussion of a new twist or two, courtesy of recent research by Urban Schrott, IT Security & Cybercrime Analyst at ESET Ireland.

Phishing and Identity Theft

Identity theft in one form or another has been around far longer than the internet, of course, but phishing doesn't require a complete assumption of the victim's identity (the sort of thing pushed to extremes in the plot of The Net). More often, it involves sending some sort of message taking on the identity of an (often real and legitimate) organization or person as part of the process of obtaining sensitive information from a potential victim in order to perpetrate fraud and/or further identity theft (which might indeed be far more extreme, but phish gangs tend to favour less dramatic attempts at impersonation of a victim, if only to reduce the risk of early discovery).

The posting of a deceptive message is only part of the phishing process: equally important is the dishonest acquisition of data from fake web sites or other data capture methods, including fake forms, keyloggers, backdoor Trojans and so on.

While phishing is often about finance-related institutions (banks, credit unions, Paypal, auction sites and so on) we should not assume that target data is always related to the victim's personal finances. In principle this kind of attack can be intended to access quite different forms of data industrial espionage, ISP account info, info relating to access to restricted systems, and so on and may be highly targeted. (Sometimes we refer to this as spear phishing, but that's a topic for a separate blog.)

Phishing from the Banks of the Liffey

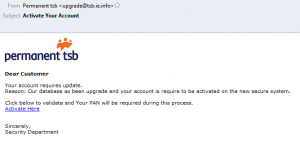

Here are a couple of examples of basic bank phish messages highlighted in a recent blog by Urban Schrott, of ESET Ireland.

The first one contains a link to what appears to be the Permanent TSB web site, but is actually a fake designed to con the victim into giving up his login credentials.

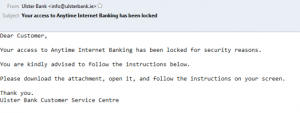

The second example arrives as an attachment to an old-school, visually unconvincing message like the one below, allegedly from the Ulster bank, which is apparently so poor it can't afford a logo...

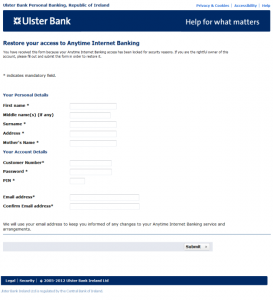

While the message is pretty crude, the attachment is the more convincing form shown here: at least, it looks reasonably official. When we look at the content, however, it turns out that you're expected to enter everything a crook might need to access your bank account, including your PIN and your mother's name (presumably this is for the infamous supplementary question "What was your mother's maiden name?".

While the message is pretty crude, the attachment is the more convincing form shown here: at least, it looks reasonably official. When we look at the content, however, it turns out that you're expected to enter everything a crook might need to access your bank account, including your PIN and your mother's name (presumably this is for the infamous supplementary question "What was your mother's maiden name?".

This is an important distinction: as a general rule, when a bank (or any other institution) asks you for your password for purposes of authentication, then by definition it wants you to give enough information to prove that you're who you claim to be. It doesn't need a whole load of other information just to be on the safe side. This isn't actually the 'greediest' example we've ever seen: some also demand full contact information, your social security number, date and place of birth, and your favourite shade of green.

(Favourite shade of green is an exaggeration, but only just...)

So far, so unpleasant, but pretty standard as phishing goes. However, in part 2 we look at something a little different.

David Harley, ESET Senior Research Fellow

Urban Schrott, IT Security & Cybercrime Analyst, ESET Ireland

< Forward to Part 2 > < Forward to Part 3 >