In recent years there has been a tremendous increase in the Russian region in the number of sites redirecting users to the Black Hole exploit kit. In most cases, successful exploitation of a vulnerability in client software leads to the installation onto the victim’s machine of either the trojan Win32/TrojanDownloader.Carberp or of Win32/Carberp (the version updated to incorporate bootkit functionality).

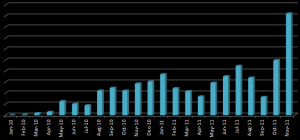

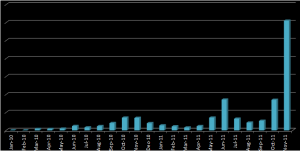

One of its most intriguing aspects is that distribution of the malware has been restricted to the most popular web sites for people managing finances in companies: these sites are visited several hundred thousand times a day. The statistics presented below clearly reflect an increase in Carberp detections in the Russian region during November. This trojan takes fifth place in the list of the most widely spread malware: Win32/TrojanDownloader.Carberp.AF - 1.73 %.

The number of detections of the Carberp family in general has more than tripled in November:

Figure 1

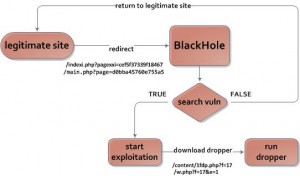

The distribution model is essentially a standard approach, but what makes it interesting is the number of legitimate web resources used to deliver Carberp onto the victim’s computers. The distribution scheme is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

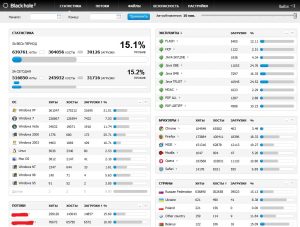

Based on the statistics obtained from one of the nodes hosting an active Black Hole exploit pack, the most frequently exploited vulnerabilities leading to system infection with malware are found in Java software.

Figure 3

In the last year Java has outpaced last year’s “leaders” in exploitable application formats such as PDF and SWF (Adobe Flash file format), which are now more or less equal in second place (Figure 3). The vulnerabilities in Java are easier and more consistently exploitable than those in PDF and SWF. The code required for a working exploit is fairly small, and may be only a page in length. The exploited vulnerabilities aren’t really new: some of them are more than a year old.

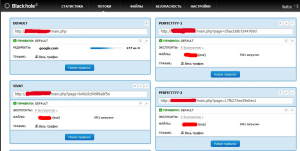

Below you can see a screenshot demonstrating the configuration window for an address to which users are redirected from legitimate web sites. There may be many such addresses. Sometimes the address is generated dynamically, based on parameters determined from the victim’s browser.

Figure 4

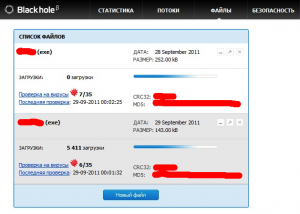

Once the vulnerability has been successfully exploited the dropper is executed: in this case it is Carberp that is being dropped. To prevent antivirus software detecting the dropper the Black Hole exploit kit includes functionality for measuring dropper detections by the most widely used antivirus software. When the number of detections reaches a defined value the dropper is repacked by the service responsible for it.

Figure 5

As we can see this is quite an effective system for exploiting vulnerabilities and installing malware on the victims’ machines. The price for Black Hole – including support – is in the order of several thousand US dollars, but cyber criminals offer rather flexible pricing: thus, it is possible to rent the service for up to a day.

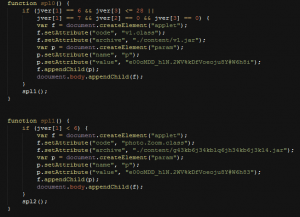

This is what exploitation of a Java vulnerability looks like:

Figure 6

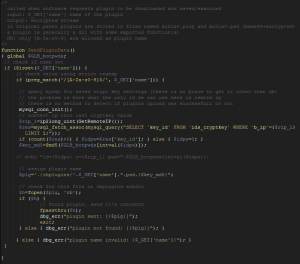

And this is a gate configuration file for distributing the Carberp dropper:

Figure 7

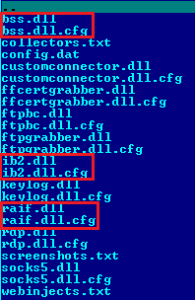

Recently we’ve been finding targeting plugins installed by Carberp in case it detects SberBank and CyberPlat payment software in the system.

In most cases the plugins are stored in publicly accessible directories and are downloaded by the malware on demand. In order to conceal the functionality of the downloaded modules they are downloaded encrypted. Here is the script to encipher the plugins:

Figure 8

An RC2 cipher and BASE64 encoding algorithm are used to encrypt data. In most cases the encryption key is stored inside BASE64-encoded data.

Another malicious program worth your attention is SpyEye. From the following chart we can see that its activity has increased significantly in November.

Figure 9

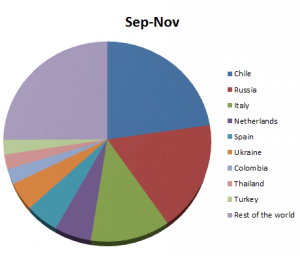

SpyEye is distributed by region as shown in the next chart (Figure 10):

Figure 10

Russia is the second largest country targeted as regards distribution of SpyEye. There is a reason for this: we’ve recently detected a SpyEye sample which downloaded plugins into the system for stealing money from Russian RBS (Remote Banking Service) systems.

Figure 11

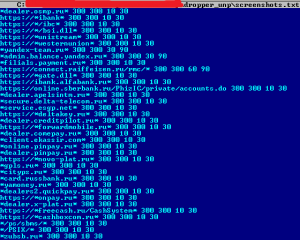

A more interesting feature is that the configuration file includes rules for taking screenshots which contain not only names of banks but also of big Russian companies:

Figure 12

All these features indicate that cybercriminal activity has been growing and evolving with respect to various payment systems.

Aleksandr Matrosov, ESET

Eugene Rodionov, ESET

Dmitry Volkov, Group-IB

David Harley, ESET